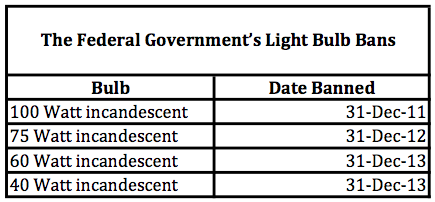

If you like incandescent 60-watt or 40-watt light bulbs, you better buy them before the end of the year because the federal government is banning these light bulbs after December 31, 2013.

Background

In 2007, Congress and President Bush decided that the American people were not wise enough to make their own choices about light bulbs. So in the Energy Independence and Security Act, they banned the importation and manufacture of standard 100 watt, 75 watt, 60 watt, and 40 watt incandescent light bulbs from 2011 through 2013.

A note about terminology—a ban by any name is still a ban

Supporters of the law try to argue that the mandate is not technically a ban, but merely an “efficiency standard.” But the simple truth is that a ban by any name is still a ban. It is illegal to manufacture or import the bulb pictured above. That is a ban on the manufacture and import of standard incandescent light bulbs.

How the light bulb ban works

The 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act limits the amount of energy “general service incandescent lamps”[1] (ie. normal light bulbs) can use to produce a certain amount of light (measured in lumens). For example, the typical 100 watt incandescent bulb produces 1600 lumens. The light bulb ban, however, mandates that bulbs which produce between 1490-2600 lumens use a maximum of 72 watts. The picture below shows Philips replacement for the standard 100 watt incandescent light bulbs.

These Philips EcoVantage lights use 72 watts, produce 1490 lumens, and they cost $5.97 ($1.49 each) at Home Depot. The bulbs are more energy efficient than standard 100-watt light bulbs because they are small halogen bulbs hiding in a normal bulb.

These Philips EcoVantage lights use 72 watts, produce 1490 lumens, and they cost $5.97 ($1.49 each) at Home Depot. The bulbs are more energy efficient than standard 100-watt light bulbs because they are small halogen bulbs hiding in a normal bulb.

What can you find on store shelves today?

At places like Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Walmart, you can no longer find normal 100 and 75 watt incandescent bulbs, but in some stores and on Amazon, you can still find 100 and 75-watt incandescents. That is because, as noted above, the law bans the manufacture and importation of these bulbs, but it does not ban their sale. The bulbs will only remain on sale until current stockpiles are exhausted.

At most stores today, instead of inexpensive incandescent light bulbs, on the shelves, you will see halogens that look like regular incandescent bulbs (such as the Philips EcoVantage pictured above), curly compact florescent lamps (CFLs), and LEDs.

Compact Florescent Lamps

Image Credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:PiccoloNamek

One likely reason Congress banned incandescent lights is because Americans are not very enamored with CFLs and one of the ways to get people to use them is to ban the incandescent competition.

CFLs were invented in 1976, but it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that they became commercially available in large numbers.[2] For years, there was a push to get people to use CFLs instead of incandescent bulbs. Some utilities, for example, have given out “free” CFLs to get people to switch.

Many people tried CFLs, hoping to save money, but for many lighting applications, CFLs are an inferior product. For example, many times CFLs fall short of advertised lifespans, especially if installed in a fixture where lights are turned on and off frequently. The Department of Energy has advised CFL consumers to leave their lights on to extend the lifespan of the bulb and make their use economical. Because CFLs are more expensive than incandescents, when they fail early, they turn out to be more expensive than a less energy efficient incandescent.

Another problem with CFLs is the light quality. CFLs emit a much cooler color temperature than traditional bulbs that cast a blue tint through a room, which can alter the appearance of paint and décor but can also leave users feeling “uneasy” or “uncomfortable”.

Beyond the aesthetic discomforts with CFL bulbs, consumers may have health concerns. The U.K.’s Health Protection Agency reported that “compact fluorescent lights can emit ultraviolet radiation at levels that, under certain conditions of use, can result in exposures higher than guideline levels.” In other words, light from CFLs can damage skin. To avoid negative effects, they warned residents not to use CFLs in lamps too close to the skin.

Another problem with CFLs is that they contain mercury. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, CFLs require an arduous disposal process to properly dispose of a used bulb. Broken CFLs can release mercury into the environment that can be dangerous. Because of this the EPA has established a ten-step clean-up process that may include a special trip to a designated recycling facility.

Lastly, some people want the bulbs in their homes and businesses simply to create a specific look and feel that isn’t possible with CFLs (or LEDs). For example, trying to make a fully restored 1800’s farmhouse feel true to period with a fluorescent bulb shaped like soft-serve is hard to do.

LED Light Bulbs

For years, CFLs were the only real alternative to incandescents. But today, LED bulbs are making CFLs obsolete for many lighting applications. LEDs are more energy efficient, produce better light, and look better than CFLs. The problem with LEDs is their extremely high price.

Currently at Home Depot (see photo below), you can buy GE’s new 60-watt replacement LED light bulb for $19.97 each, while the incandescent 60 watt light bulbs are $1.58 for a 4-pack. In other words, a single 60-watt incandescent costs $0.40 and the replacement LED costs $19.97—50 times more!

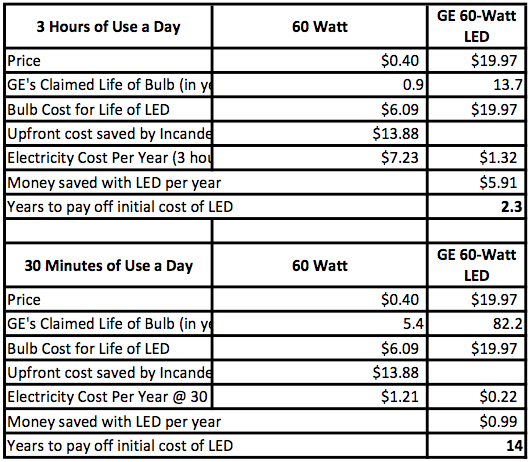

The more energy efficient LEDs take years to make up their high upfront cost. According to GE’s assumptions about price and longevity, if you use the 60-watt equivalent LED bulb pictured above for three hours a day compared to the 60-watt incandescent in the same picture, you will recoup the cost of the LED bulb in 2.3 years. If, however, you only used the bulb for 30 minutes a day, it would take 14 years to recoup the cost of the bulb.

Here is the explanation of the calculation. According to GE’s assumptions, an incandescent bulb, if it is used for 3 hours a day, will burn out in 9/10ths of a year, while an LED bulb will last for 13.7 years. That means that if a single incandescent bulb costs $0.40, over the life of an LED bulb, you will pay $6.09 to buy incandescent bulbs. In other words, you save $13.88 in the cost of bulbs if you bought incandescents instead of a LED.

LEDs use much less electricity than incandescent lights. If electricity costs $0.11 per kWh, and the bulbs are run for 3 hours a day, over the course of a year using a 60-watt incandescent would cost $7.23 while the electricity to run the LED would cost $1.32. This means that the LED would pay for itself in saved electricity in 2.3 years.

But many people do not use certain lights for 3 hours a day and instead us them far less. The second table below shows the payback period using the same methodology but assuming the bulb is only used for 30 minutes a day. With these assumptions, it would take 14 years for the LED bulb to pay for itself.

The upshot of this calculation is clear. It makes sense to replace incandescents with LEDs if the bulb is used for hours a day. If, however, the bulb is not used much in the course of the day, incandescents make more sense.

These calculations assume that the LED bulbs actually last for 13.7 years. Because LED bulbs are new technology, it makes sense to view this with some skepticism. This is especially true because CFLs frequently failed to live up to their long-lived billing. Furthermore, questions exist about advertised reliability and lifespan of some LEDs. These bulbs might have thermal management issues (ie. they can get too hot and fail) and earlier this year a half million LEDs were recalled due to a fire hazard.

Conclusion: if you like your light bulb, you should be able to keep your light bulb

For certain applications, new LEDs have real benefits over incandescents and CFLs. Likewise, CFLs can save people money compared to incandescents. But just because LEDs or CFLs can save you money for certain applications is no reason to ban incandescents altogether. A much better solution is to provide people with information and allow them to make their own, educated choices. After all, in certain applications, such as where a light bulb may frequently break, an incandescent light bulb will save people money.

Incandescent light bulbs have a long track record, they produce pleasing light, their characteristics are known, and they are inexpensive. The choice of whether to use incandescents, LEDs, or CFLs should be up to the homeowner, not Congress, the President, or bureaucrats.

In 2011, many in Congress realized that the 2007 ban on incandescents was anti-consumer and there was an effort in Congress to change the law. While the bills to repeal the law failed, however, Congress succeed in defunding enforcement of the light bulb ban for a year. Even this half-measure was criticized by the ban proponents. Sen. Jeff Bingaman stated “If America is to have a rational energy policy, we need to make progress in efficiency.” He continued, “Blocking funds to enforce minimum standards works against our nation getting the full benefits of energy efficiency.”

Sen. Bingaman’s statement is a good example of why the light bulb ban is flawed. Besides insinuating that it is irrational not to ban incandescents, he is fully in favor of banning things to get “the full benefits of energy efficiency.” This begs the question, “where does the government stop banning things to save energy?”

If it is appropriate to ban incandescent light bulbs (technically to impose an efficiency standard regular incandescent light bulbs cannot meet) then why not do the same for fuel economy of cars and trucks. The Obama administration is well on its way with the fuel economy standards which will require average fleet fuel economy of over 54 miles a gallon by 2025. But if, to quote former Sen. Bingaman, we want the “full benefits of energy efficiency,” why not go further. What’s wrong with 70 miles per gallon? What’s wrong with fuel economy mandates which essentially ban large cars and trucks?

Or, if we want to receive the “full benefits of energy efficiency” then why not impose an energy efficiency standard on the amount of electricity sports venues are allowed to use for football games, baseball games, or basketball games. Wouldn’t it be much more energy efficient to play games in the day, during the sunshine, than use energy-consuming lights at night?

The reality is that the federal government treats the American people like children when it comes to energy use. The federal government imposes roadblocks and bans on certain energy use instead of taking a more adult approach and proving people with information and letting them make their own choices.

If you like your light bulb, you should be able to keep your light bulb, to paraphrase President Obama. But since the federal government decided to ban certain light bulbs, make sure to stock up at Amazon, eLightbulbs.com, or wherever else you can find 75 and 100-watt light bulbs and 60 and 40-watt light bulbs after December 31st.

Daniel Simmons and IER Policy Associate Landon Stevens authored this post.

[1] See EISA §321 Efficient Light Bulbs, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-110hr6enr/pdf/BILLS-110hr6enr.pdf.

[2] Lamptech, Philips Tornado Asian Compact Fluorescent, http://www.lamptech.co.uk/Spec%20Sheets/Philips%20CFL%20Tornado.htm