Earlier this month I participated in a carbon tax panel discussion before lawmakers and legislative staff members at the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill. Since the GOP’s tax overhaul is on Washington’s agenda, I explained why a new carbon tax would be the opposite of the standard goals of pro-growth reform of the tax code. To illustrate my point, I used an analogy with the car market that seemed to resonate with the audience, so I’ll summarize my argument here for IER’s readers.

A Tax on Cars

Suppose the government wants more revenue, and so decides to levy a $1,000 tax on every new car sold in America. Analysts come up with estimates that the new tax will raise such-and-such billion dollars in new receipts for the Treasury.

Now further suppose that someone suggests tweaking the plan. “Look,” the guy says, “right now red cars constitute 20% of the overall market. So instead of levying a $1,000 tax on all cars, we can achieve the same outcome if we instead levy a $5,000 tax just on red cars.”

This is a very bad suggestion, from the point of view of textbook tax analysis. Most obvious, it seems arbitrary and unfair. Why should people who like red cars have to pay a $5,000 tax, when the people who prefer silver cars or brown cars get to pay nothing?

But beyond the arbitrariness and unfairness, there is the problem that with a narrow car tax—which only targets 20% of the market—consumers will adjust their behavior. People who originally planned on buying a red car might instead buy a silver car, and thereby avoid the $5,000 tax.

Because many people will respond this way, it means that the government won’t raise the same amount of revenue from the two possible approaches. If the tax is going to be concentrated just on red cars, then it will have to be made higher—maybe $6,000—to account for the fact that the proportion of red cars in the overall market will shrink, due to the tax. This of course only increases the unfairness of the burden that is being placed on the shoulders of red car enthusiasts.

Yet it gets worse. When the dust settles, there is a permanent loss to society from this onerous tax on red cars. Specifically, there are a lot of people—perhaps millions of them—who were induced to drive a non-red car, even though they would have preferred a red car in the absence of the new tax. So these people are definitely worse off; they’re driving a car with a color they don’t really like.

Unfortunately, there is no corresponding gain to anyone in society from their unhappiness. Remember, these particular drivers aren’t paying any tax; they switched to a non-red car in order to avoid the tax. So the government isn’t gaining any revenue from them, and their unhappiness (at having to drive a non-red car) is a pure loss. Economists refer to this type of outcome as deadweight loss. It is the drag on the economy—the missing out of “win-win” market exchanges—due to inefficient taxation.

Lessons From the Hypothetical Tax on Red Cars

To be sure, my story is contrived, but it serves to illustrate a real and important point: Generally speaking, if the government wants to raise revenue by taxing a certain activity or sector, then it’s best to apply the tax to as wide a base as possible, in order to raise the target amount of revenue with as small a tax as possible.

This combination of a wide base and a low level for a tax will allow the government to siphon out its desired amount of revenue, while distorting economic behavior as little as possible.

To reiterate the lesson from our example: A hypothetical $1,000 tax applied to all new cars will distort behavior; some people will postpone their purchase of a new car. However, a $5,000 tax applied to only one-fifth of the car market (to red cars, say) will distort things much more, both because of the higher amount and because it’s easier to buy a non-red car than to not buy a car at all. (The distortion is amplified when the legislators realize that their $5,000 tax on red cars doesn’t raise the same revenue as a $1,000 tax on all cars, and so they have to increase the red car rate.)

The Lesson Applied to a Carbon Tax

Now that we’ve considered tax design in the case of the car market, suppose that the government wants to raise $2 trillion over the next ten years with a new tax. It can levy a flat “head tax” that divides the burden evenly across all American taxpayers, or it can slap the $2 trillion tax just on activities that emit a lot of carbon dioxide. Putting aside issues of climate change for the moment, which proposal makes the most sense in terms of standard economic growth?

It should be obvious that the first proposal is much more efficient. By levying a uniform head tax that isn’t tied to behavior, the government would raise the $2 trillion without distorting activity very much. People would be poorer, and the government would be richer, but there wouldn’t be too much deadweight loss that added insult to injury. It would mostly be a pure transfer of wealth from the taxpayers to the government.

In complete contrast, the $2 trillion (over 10 years) tax levied on carbon-intensive industries would completely alter behavior. Indeed, that is the whole point of a carbon tax—to utterly transform the way our economy produces energy and provides transportation. So in addition to the taxpayers as a whole being $2 trillion poorer, they would also be doing things that weren’t as productive as the original method. Some people would be driving electric cars, for example, who would have preferred to drive gasoline-powered cars, and these people wouldn’t be contributing much in carbon tax revenue to the government. Instead, their unhappiness (at having to drive an inferior vehicle, or paying higher prices for electricity that was produced by wind power instead of coal) would be part of the deadweight loss to society from the carbon tax.

Now it’s true, the promoters of the carbon tax could argue that it yielded environmental benefits that counted against the deadweight loss I’ve described. But it should be clear that just focusing on conventional economic output, raising $2 trillion through a lump sum head tax would impose much less drag than raising the same amount of revenue via a tax narrowly targeted to the carbon-intensive segment of the economy.

Making Sense of “Tax Swap” Estimates

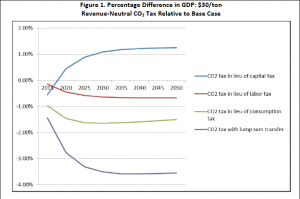

After our above discussion, let us turn again to a familiar chart that I’ve highlighted in previous IER posts. Below, I reproduce a figure from a Resources for the Future (RFF) study, which analyzed the impact of various proposals to impose a carbon tax and then use the revenues to fund a dollar-for-dollar refund to the taxpayers:

Source: Carbone et al., Resources for the Future 2013.

In the diagram above, look at the purple line. This is showing what happens to the economy if a $30/ton revenue-neutral carbon tax is used to fund lump-sum dividend payments back to all citizens. Notice that in the long run, this proposal ends up making annual economic output (i.e. GDP) some 3.5% lower than it otherwise would be.

In light of our earlier analysis, this result should now be perfectly intuitive. We’ve already walked through the logic of why a $2 trillion tax imposed in a lump sum fashion would distort the economy far less than a comparable tax imposed on carbon-intensive industries.

So, if we simply reverse the logic, we can see that imposing a huge new carbon tax while simultaneously lowering taxes in a lump sum fashion, would still leave citizens worse off, if we just consider conventional GDP (and leave climate change issues to the side for now). Yes, giving resources back to the citizens in the form of lump-sum payments is nice, but it doesn’t alter their behavior in ways that promote economic growth. So the mere fact that the carbon tax is revenue neutral doesn’t render it harmless. No, the carbon tax still greatly changes behavior—remember, that’s the whole point of a carbon tax—and the lump-sum rebate won’t undo the distortion.

As the diagram shows, the other proposals for “recycling” the revenue back to the citizens are not as destructive. Indeed, taxes on capital (top blue line) are so distortionary that the RFF model found them even more harmful than the carbon tax. But in general, the results show that most of the other methods of raising revenue are less harmful than a carbon tax. The mirror image of that statement, of course, means that even a revenue-neutral carbon tax would hurt the economy, except for the politically implausible scenario where all of the receipts from a regressive carbon tax are funneled into tax cuts for rich capitalists.

Conclusion

If proponents of a carbon tax want to admit that it will impose a significant drag on conventional GDP growth, but with the benefit of mitigating climate change for future generations, then we can have that discussion. However, a small but vocal group of academics and former government officials has been promising conservatives and libertarians that they can have their cake and eat it too. Namely, they have promised that a “carbon tax swap” deal will allow a win-win outcome, where we get far lower emissions and a boost in conventional GDP growth.

As this post has made clear, such promises are empty. On the face of it, a carbon tax is the opposite of what is needed for “tax reform.” To engage in pro-growth, supply-side tax reform, the objective is to raise the target amount of revenue from as large a tax base and as small a rate as possible. The point is to skim receipts from the economy while changing behavior as little as possible.

Notice that by its very design, a carbon tax works against such “reform.” Rather than applying to a wide base, a carbon tax hits a narrow segment of the economy. And rather than minimizing the impact on behavior, the whole point of a carbon tax is to make people work and consume differently.

These considerations underscore why a carbon tax would pose a significant drag on conventional GDP growth, which would work against any alleged environmental benefits down the road. Perhaps that tradeoff is worth it, but too many promoters have been misleading Americans by promising that such a tradeoff doesn’t exist.