In 2010, Germany embarked on a forty-year experiment in energy central planning in an effort to reduce the country’s carbon footprint by transitioning away from fossil fuels. The country’s energy transition, known as the Energiewende, includes greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions of 80-95 percent by 2050 (relative to 1990) and a renewable energy target of 60 percent by 2050. Legislative support for the energy transition was passed in September of 2010. In June of 2011, in reaction to the Fukushima nuclear accident caused by the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Germany’s government removed nuclear power as a source of bridging fuel as part of the energy transition. As recently as January of 2019, Germany’s plan was to abandon nuclear energy completely by 2022. In July of 2020, Germany passed legislation to end coal-fired power generation by 2038.

Last year, wind and solar energy advocates rejoiced as renewable energy’s share of Germany’s overall power supply increased by 5.4 percent to 46 percent of the total. In 2019, wind (both onshore and offshore) produced 24.6 percent of Germany’s total energy mix; nuclear produced 13.8 percent; natural gas produced 10.5 percent; ; solar produced 9 percent; biomass produced 8.5 percent; and hydropower plants produced 3.8 percent.

Germans Pay More

IER’s audience should not be surprised that Germany’s energy transition has coincided with steadily rising energy prices. According to the German Association of Energy and Water Industries, in 2019 the monthly electricity bill for an average German household According to data from the EU, today German households and industry pay the highest electricity prices in Europe. To provide some perspective, according to data from the World Bank, the average price of electricity in Germany was 32.2 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour in 2019 compared to 17.1 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour in the U.S.

Because wind and solar energy are intermittent sources of energy that are not competitive in an open market, Germany’s energy transition has been driven by a system that forces German power consumers to help finance wind and solar projects through a surcharge in their monthly electric bills. The surcharge is based on the difference between payments made to investors and the wholesale power price. As of 2019, the renewables surcharge accounted for approximately one fifth of a German household’s electric bill.

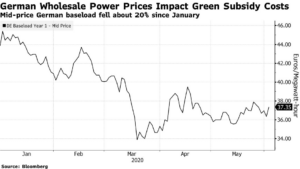

More recently, these surcharge prices have sky-rocketed as wholesale power prices in Germany have fallen 20 percent since January due to the drop in demand caused by the pandemic.

This drop in wholesale prices means that consumers have seen their the green surcharges rise because those surcharges are determined by the difference between payments made to investors in green energy projects and wholesale prices. Hans Josef Fell, one of the original architects of this green financing program, was quoted in a recent piece at Bloomberg article explaining that the surcharge will cost . These rising surcharges forced Chancellor Angela Merkel to recently cut the surcharge by €0.02 for every kilowatt-hour next year at a cost of €11 billion to Germany’s budget. However, this isn’t much of a fix as it simply shifts the costs from power consumers to the taxpayers.

Interventionism Run Amok in Germany

Germany should serve as a cautionary tale for the U.S. as it provides an example of what the path to 100-percent renewable energy will look like as the high energy prices in Germany are one part of the inevitable disorder brought about by political intervention into the energy market. This process of intervention was spelled out by the late economist Don Lavoie:

Attempts to violently manipulate the outcomes of [the market] process lead to reactions that the intervener can neither specifically predict nor effectively prevent. Efforts to make the initial intervention work as designed must take the form of ever-wider and more obtrusive interventions, which are in further conflict with the workings of the market mechanism. In the end the interventionists must either extend their activities to the point where the process has been completely sabotaged or they must abandon their quest to control the market. Any ‘middle way’ between the extremes may, of course, be advocated but would consist in a series of haphazard shocks to the system.

Indeed, everywhere you look in Germany politicians and bureaucrats are scrambling to install a new patchwork of interventions in order to rescue their experiment in energy central planning. Last year, the Merkel government removed a cap on solar power subsidies in order to further increase capacity. Additionally, Germany is one of the most generous subsidizers of electric vehicles in Europe, offering up to $10,000 in subsidies to EV buyers. These interventions have accelerated in response to the COVID pandemic as Germany has undertaken a $145 billion (€130 billion) “recovery plan” with $48.7 billion going to renewable energy and electric vehicles. No doubt, Germany seems to be on a path where the government will soon face a decision to either abandon their attempts to control the energy market, or take total control of the country’s energy industry.