“How is it that wind, with a 4000-year head start, is such a small player in the energy scene? Could it be—just possibly—that the answer has something to do with physics instead of economics and politics?”

– Howard Hayden. Quoted in Michael Economides, “The Rhetoric and Reality of Renewables,” August 15, 2011.

“The use of wind power is as old as history,” resource economist Erich Zimmermann observed in his 1951 treatise, World Resources and Industries.[1] “With wind energy, one is not dealing with exotic new techniques,” a Resources for the Future energy overview concluded in 1979. “Windmills have been used for centuries for pumping water and other purposes, and within the past century they have been widely used in rural areas to generate electricity.”[2]

Energy history explodes the fallacy that wind energy is something new and futuristic, while fossil fuels are … so yesterday. What forced energy transformationists, the would-be central planners, see as new and exciting is really ancient and lacking; and what is seen as old is really new and successful.

Coal, oil, and gas are only several hundred years old as primary energies; renewable energies are as old as human time. Solar and wind and falling water and burning plants and trees–renewables all–are caveman energies. In fact, the market share of renewable energy has been virtually 100 percent for most of mankind’s history. Renewables can be thought of as poverty energies, just as oil, gas, and coal are considered modern energies.

Wind’s Ancient Problem: Intermittency

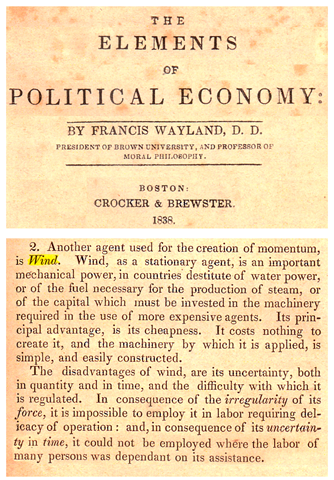

The Elements of Political Economy by Francis Wayland was an economics textbook in 1838 which explained the problem with wind, a problem that remains at the center of the renewable energy debate nearly 175 years later.

Windpower is its own worst enemy because it tries to turn a dilute, intermittent resource into an industrial grade one. The winds blow most steadily when people are not, requiring siting in pristine places distant from the load centers. Can there be a more perfect imperfect energy?

The long history of wind energy, and the more recent failed history of windpower, is well substantiated in the energy literature. Some quotations are presented below to land the fact that the infant industry argument for continuing hitherto-failed government support is throwing good money after bad.

U.S. Windpower History: 1888s

“U.S. Wind Engine and Pump Company of Batavia, Illinois, conducted intensive experiments in 1882 and 1883 on various kinds of windmills to determine the best possible machine for use. Part of their investigation involved building windmills to the specifications offered by Englishman John Smeaton, in his work of the previous century. Smeaton observed in 1759 that fewer sails were needed to extract the equivalent amount of power.”

– Wilson Clark, Energy for Survival: The Alternative to Extinction (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1974), p. 522.

“The first wind turbine used to convert wind energy into power—unlike windmills, which are used to pump water or grind grain—was built by Professor James Blyth of Anderson’s College, Glasgow (now Strathclyde University) in 1887. Blyth’s experiments with three different turbine designs resulted in a 10-meter-high (33-foothigh), cloth-sailed wind turbine, which was installed in the garden of his holiday cottage at Marykirk in Kincardineshire. It is said to have operated for 25 years.”

– Sonal Patel, “Changing Winds: The Evolving Wind Turbine,” POWER, April 1, 2011.

“Blyth’s invention marked the dawn of wind turbine development. Close on its heels was a turbine built by American inventor Charles Brush in 1888. That 12-kW turbine featured 144 blades made of cedar, each with a rotating diameter of 17 meters. Then came the work of Danish scientist Poul la Cour in the 1890s, which spawned about 2,500 turbines in Denmark by 1900, with an estimated combined peak power capacity of 30 MW. La Cour’s wind turbines produced hydrogen as well as power.”

– Sonal Patel, “Changing Winds: The Evolving Wind Turbine,” POWER, April 1, 2011.

U.S. Windpower History: 1940s

“An experimental 1,250-kilowatt Smith-Putnam wind turbine was built on Grandpa’s Knob in Vermont in 1940. . . . In the course of 5 years of experiments, the engineers in charge concluded that the major mechanical problems had been solved, and that a unit could be designed to remain safely on line in any wind. Several hundred cost studies . . . concluded that the economically optimum wind-turbine would stand about 165 feet high, with a diameter of about 225 feet and a rating of about 2,000 kilowatts—virtually regardless of the wind volume.”

– The Paley Commission, Resources for Freedom: The Promise of Technology, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1952), p. 218.

“The Federal Power Commission became interested in the Grandpa’s Knob [windpower] experiment during World War II, and commissioned Percy H. Thomas, a senior engineer of the commission, to investigate the potential of wind power production for the entire country. Thomas’ survey, Electric Power from the Wind, was published in March 1945.”

– Wilson Clark, Energy for Survival: The Alternative to Extinction (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1974), p. 545.

“During the second World War, a massive 1,250-kilowatt wind electrical station was operated at ‘Grandpa’s Knob’ in the mountains of central Vermont. . . . [This] power that the wind generator produced during sporadic periods of operation were fed into the lines of Central Vermont Public Service Corporation. The plant was conceived and designed by Palmer C. Putnam, an engineer who had become interested in wind power in the early 1930s when he built a house on Cape Cod only to find both the winds and electric utility rates ‘surprisingly high.’”

– Wilson Clark, Energy for Survival: The Alternative to Extinction (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1974), pp. 541-42.

Remember energy history next time a windpower lobbyist calls for just a bit more time for special government support. Time’s up.