Studies have found that wind turbines are a dangerous threat to bats, high-conservation value birds, and insect populations that are a major supply of food to bats and birds. Insects, birds, bats, and wind farm developers are attracted to the same thing—high wind speeds. Wind farms in Europe and the United States are being built in the path of migration trails that have been used by insects and birds for millions of years. Researchers found that wind turbines in Germany resulted in a loss of about 1.2 trillion insects of different species each year. Researchers in India found almost four times fewer buzzards, hawks, and kites in areas with wind farms—a loss of about 75 percent. They found that wind turbines are akin to adding a top predator to the ecosystem, killing off birds, but allowing small animals to increase their populations resulting in a trickle effect throughout the ecosystem.

Migratory Bats and Birds

Wind turbines are the single greatest human threat to migratory bats, which live in different habitats during summer and winter months. Some, like the hoary bat, fly south to Mexico during the winter as insects become scarce in North America. In 2017, scientists warned that the hoary bat could become extinct if the expansion of wind farms continues.

Wind turbines have also become one of the greatest human threats to many species of large, threatened and high-conservation value birds. Wind energy threatens golden eagles, bald eagles, burrowing owls, red-tailed hawks, white-tailed kites, peregrine falcons, and prairie falcons, among others. The expansion of wind turbines could result in the extinction of the golden eagle in the western United States, where its population is at a very low level.

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru studied lizard and bird populations at three wind turbine sites. In areas without turbines around 19 birds were spotted every three hours, while only five were sited nearer the turbines. The lower rate of predatory birds led to an abundance of the fan-throated lizard. The lower number of predatory birds has a “ripple effect” across the food chain with small mammals and reptiles increasing in number as their natural predators disappear and changing their behavior as they become less fearful of predators.

Deaths of big birds have a greater impact on their population than smaller birds because they have lower reproductive rates. For example, golden eagles will have only one or two baby chicks at most once a year while robins could have three to seven baby chicks as often as twice a year.

Insect Populations

For three decades, scientists have reported the build-up of dead insects on wind turbine blades in different regions around the world. Researchers in Germany found a 76 percent decline in flying insect biomass in conducting a 27-year population monitoring study. Wind turbines are contributing to what is called the “insect die-off.” The German insect death toll from wind turbines of 1.2 trillion per year is one-third of the total annual insect migration in southern England.

Insect die-off also reduces the efficiency of the wind turbines. In 2001, researchers calculated that the build-up of dead insects on wind turbine blades can reduce the electricity they generate by 50 percent.

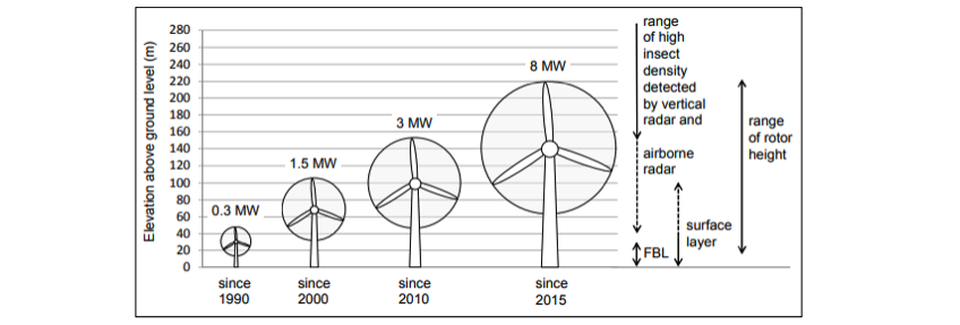

In the 1990s, the wind industry claimed its turbine blades were too high to threaten flying insects and that insects flew too slowly to be impacted. Since then, it has been found that insects cluster at the same altitudes used by wind turbines. Scientists in Oklahoma found that the highest density of insects is between 150 to 250 meters, which overlaps with large turbine blades that stretch from 60 to 220 meters above the ground.

Insect Cluster at the Same Altitudes Used by Wind Turbines

Government Intervention

While government agencies require the oil and gas industry to report bird deaths and pay fines for any found, wind farms are exempt, even though the wildlife impacts can be far greater. Wind developers are allowed to self-report violations of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, wind developers can avoid prosecution for killing eagles by applying for licenses to cover the number of birds who might be struck by their wind turbines. In rare circumstances when governments require the wind industry to mitigate the impact of bird deaths, such as by setting aside land elsewhere, there is often little or no enforcement.

Curtailing wind energy by halting the turbine blades is the only way to reduce the killing of birds, bats and insects by wind turbines. Scientists have found that curtailing wind turbines when wind speed is low can reduce bat fatalities by 44 percent to 93 percent. However, very few wind farm developers are willing to curtail their wind production. An NREL study found that curtailment levels are lower than 5 percent of total wind energy generation.

Conclusion

Wind developers and operators should not be given a free rein to kill birds, bats, and insects and to disrupt the ecosystem. They should be held accountable for these deaths and be fined as any other industry. The problem will only get worse as more wind farms are forced onto the grid as state mandates for renewable energy are achieved.