The wind and solar industries have been lobbying Congress to extend the production tax credit and the investment tax credit during the negotiations on the coronavirus relief bills because “clean energy” employment is down due to the coronavirus pandemic. While the original purpose of the tax credits was to spur the advent of young industries, these industries are now decades old and should be able to advance without continued support from lawmakers. The tax credits should be phased out as current law intends.

Wind Energy Tax Credits

Wind power is not a new technology. It has been around for centuries. The United States attempted to develop a wind industry in the 1970s beginning in California (e.g., in the Altamont Pass and in other areas), only to later see its stagnation. Though because of state mandates and federal and state incentives, wind turbines are better constructed, more efficient, and less costly today, wind remains a minor contributor to the U.S grid.

The laws of about half of the states require a certain percentage of electricity to come from qualified renewable energy sources (generally wind and solar technologies) and federal laws have given large subsidies to the industry. In fact, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), federal subsidies for wind energy increased 10-fold between fiscal year 2007 and fiscal year 2010—a three year period. Between 2007 and 2010, wind generation increased 175 percent, increasing from a 0.8 percent share of generation in 2007 to 2.3 percent in 2010. But to get there, the government had to spend $5 billion in subsidies in fiscal year 2010 alone. For every megawatt hour of wind energy generated, the taxpayer paid $56, compared to 64 cents for coal-fired and natural gas-fired generation. According to EIA, 97 percent of the $5 billion in subsidies to the wind industry in fiscal year 2010 was due to the stimulus (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009).

Between FY 2010 and FY 2013, wind subsidies increased another 8 percent and wind increased its share of the generation market to 4.1 percent. In fiscal year 2016, the last year EIA produced a subsidy study, wind subsidies totaled $1.27 billion (2016 dollars), consisting mostly of tax expenditures, and it generated 5.6 percent of U.S. electricity—far less than coal and natural gas generation, which generated 64 percent of U.S. electricity.

Wind energy is not without its problems. It generates electricity only when the wind is blowing, regardless of whether electricity demand is high or low. This means that wind does not have much capacity value because it cannot be dispatched on an as-needed basis as coal and natural gas-fired technologies can. Thus, wind gets preferential treatment when it is available so that state mandates can be met and the industry can receive its production tax credit, which literally pays them to generate electricity, regardless of whether it is needed at that time.

While the tax credits were supposed to be temporary to allow for a young industry to get off its feet, they have now been in place for 28 years—more than enough time for the industry to reach adulthood. The wind production tax credit has been extended a dozen times since 1999 and the Democrats in the House of Representatives want to extend it again under the guise of coronavirus relief. Only this time, they want to allow for the option of direct payments rather than a credit on investors’ taxes, which they believe will encourage investment. Currently, someone with a tax obligation to the government gets that obligation reduced on a direct dollar basis; this would allow companies that do not pay taxes to receive federal aid. The U.S. Treasury estimates that the existing form of the Production Tax Credit will cost taxpayers $40.12 billion from 2018 to 2027, making it the most expensive energy subsidy under current tax law.

The production tax credit provides wind energy facilities with a tax credit for the first 10 years a qualified facility is in operation. In 2013, the production tax credit for wind generation was 2.3 cents per kilowatt hour for the first 10 years of production, with adjustments for inflation. Under the phase out of the credit approved by Congress, the tax credit decreased by 20 percent per year from 2017 through 2019. The Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2019 extended the production tax credit for facilities beginning construction during 2020 at a rate of 60 percent—higher than the 40 percent rate for 2019. Currently, wind energy facilities that begin construction after the end of 2020 cannot claim the credit, although they will still be required to be built by state mandates referred to as “renewable portfolio standards.”

The production tax credit came about as part of the Energy Policy Act of 1992 and was supposed to be short-lived to spur the deployment of a “young” industry. Despite its 28 years of existence and wind advocates indicating that wind is now cost-competitive with traditional generating technologies without the credit, the industry is still lobbying for its extension again. But the credit has several perverse effects.

For one, it disrupts the economics of generation, causing wholesale generating prices to drop below zero at times and compelling other technologies to accept those prices. Because wind producers are paid by taxpayers to operate, a wind producer can still profit while paying the grid to take its electricity, producing negative prices. When the price becomes negative, electric generators are actually paying the grid to take their electricity. Fundamentally, negative wholesale prices send a distress signal telling markets that the supply and demand balance on the grid is economically unsustainable and suppliers need to reduce their output. But these market signals do not apply to wind energy facilities since they are paid by taxpayers to produce electricity whether it is needed or not. It is Uncle Sam’s large thumb on the scale saying “produce electricity whether it is needed or not.”

The production tax credit also obscures the true cost of generating electricity by forcing tax payers to subsidize it. Wind does not blow all the time, so it must have back-up power, typically coal-fired or natural gas-fired power plants that can provide power when demanded. That means that ratepayers are essentially paying twice—once for wind turbines that generate the wind power and then for the natural gas- or coal-fired power that provides the back-up electricity when the wind isn’t blowing. Further, wind power is the greatest when we least need it–at night and during the very early morning when electricity is least demanded. The cost of back-up power is not included in estimates that forecasters provide for wind power, nor is the cost of another potential backup source—utility scale batteries, which are extraordinarily expensive and only required because of the subsidized and mandated intermittent renewable energy sources.

Besides cost and reliability, other wind problems include noise pollution, the need for large amounts of land, and the destruction of bats and birds—especially rare birds of prey—that come within the path of the turbine blades. Additionally, most favorable wind production areas are remotely located far from consumers, and therefore require expensive and inefficient energy transmission systems to be built (and paid for by consumers in their utility bills).

Oil and Gas Tax Deductions

Frequently, when the issue of extending wind and solar tax credits comes up, environmentalists and some lawmakers point to “taxpayer subsidies to big oil companies,” as a reason to continue them. But these are tax deductions, not credits, that are mainly targeted to small independent oil and natural gas producers, rather than the major integrated oil companies usually described as “big oil.” One of the tax deductions is provided to all U.S. manufacturing firms, not just oil and gas producers, while the others are for typical business deductions in the tax code akin to research and development costs available to all industries.

The two tax deductions that primarily affect small independent producers are the percentage depletion allowance and expensing of intangible drilling costs. As the oil and gas in a well is depleted, independent producers are allowed a percentage depletion allowance to be deducted from their taxes. While the percentage depletion allowance sounds complicated, it is similar to the treatment given other businesses for depreciation of an asset. The tax code essentially treats the value of a well as it does the value of a newly constructed factory, allowing a percentage of the value to be depreciated each year. This allowance was first instituted in 1926 to compensate for the decreasing value of the resource, and was eliminated for major oil companies in 1975. This tax deduction is estimated to save the independent oil and gas producers about $0.4 billion in fiscal year 2020.

Independent producers are also allowed to count certain costs associated with the drilling and development of wells as business expenses. The law allows the small producers to expense the full value of these costs, known as intangible drilling costs, every year to encourage them to explore for new oil. The major companies get a portion of this deduction—they can expense a third of intangible drilling costs, but they must spread the deductions across a five-year period. This tax treatment is also similar to that of other businesses for such investments as research and development. This tax deduction is estimated to save the independent oil and gas producers about $0.4 billion in fiscal year 2020

Another tax deduction is the Domestic Manufacturing tax deduction, which allows all industries and businesses (not just oil companies) to deduct a certain percentage of their profits—for the oil and gas industry, it is 6 percent, for all other industries (software developers, video game developers, the motion picture industry, and green energy producers, among others), it is 9 percent.

Comparison of Major Tax Incentives

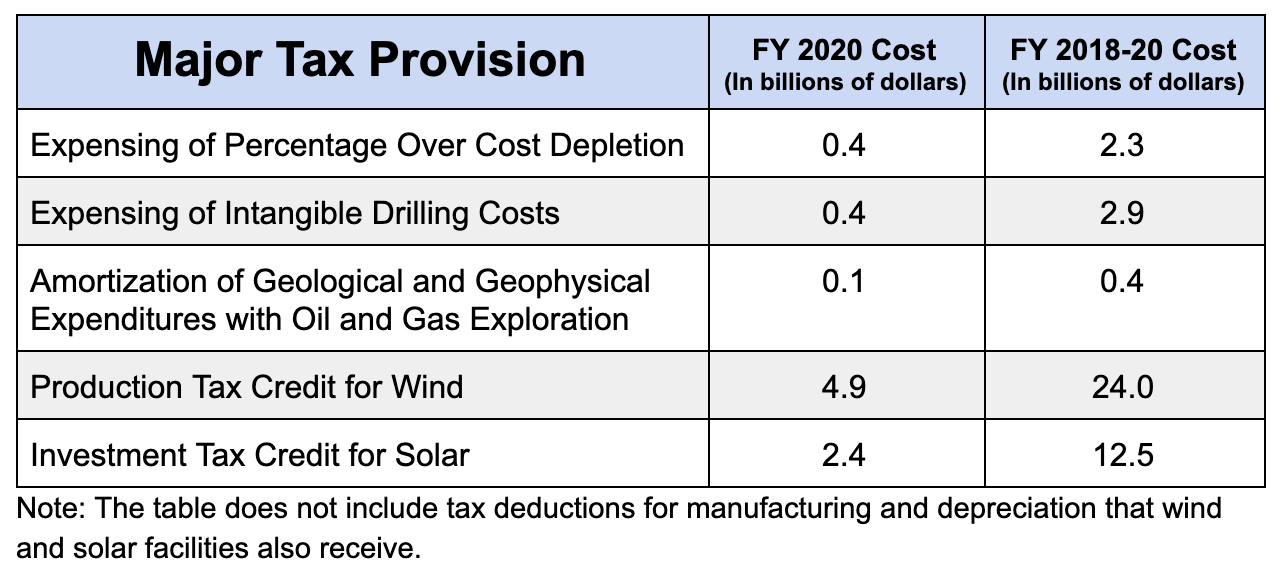

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the production tax credit for wind is estimated to cost taxpayers $4.9 billion in fiscal year 2020, the investment tax credit for solar is estimated to cost $2.4 billion, and the three tax deductions for oil and gas listed below combined are estimated to cost $0.9 billion. Clearly, the wind and solar tax credits outweigh the tax deductions of oil and gas companies by a factor of 8 in fiscal year 2020. Further, this comparison does not include the tax deductions that the wind and solar industries get for depreciation and manufacturing.

When compared to the relative amounts of energy produced by the differing sources, taxpayers are getting little benefit from wind and solar and a great deal of benefit from oil and natural gas. Almost all of our transportation is fueled by oil, and natural gas is the largest source for both heating homes and making the electricity that cools our homes, fuels our factories and schools and hospitals, and makes modern life possible.

Conclusion

The wind industry is pushing for an extension of the production tax credit and they justify this demand with environmentalist complaints about the tax deductions available to the oil and gas industry. But the advantages and disadvantages of these incentives vary greatly in terms of benefits—revenues to the government, employment, and energy contribution. Even if you accept the environmentalist argument about tax deductions, the small tax benefits available to oil and gas producers pales in comparison to the vast sums of taxpayer money being handed to wind and solar generators. In return, even after all these billions, the US economy only gets less than 4% of its energy from wind and solar, compared to 69% from natural gas and oil. However you slice it, the wind PTC is a bad deal for taxpayers.