The PTC was intended to be a temporary subsidy for a fledgling industry but has morphed into a massive handout for large corporations, many of which are foreign owned—all at the expense of the American taxpayers. It’s a textbook case of corporate welfare…. It’s past time for the wind industry to sink or swim on its own merits.

– Thomas Pyle (American Energy Alliance), “PTC Elimination Act Protects American Families,” April 22, 2015.

The governmental quest to make wind competitive as grid electricity rests on historical and theoretical sand. Historically, it has been believed that wind power is a young industry, requiring outsized tax preferences, bureaucratic R&D, and sales guarantees to rival fossil-fuel-generated electricity. Theoretically, it was believed that large-scale production from such protectionism would make wind competitive enough to remove the subsidies.

In fact, industrial-size wind turbines have a long history of entrepreneurial effort, and their technologies are as dependent on taxpayer and ratepayer subsidies today as they were several decades ago. (The essay “The Economic Fall and Political Rise of Renewable Energy” fills in much of this history.)

Competitiveness has not arrived—for the fundamental reason that dilute, intermittent energy cannot compete against dense, storable, portable rivals. Little wonder that James Hansen, father of climate alarmism, has dismissed renewables as “almost the equivalent of believing in the Easter Bunny and Tooth Fairy.”

Yet wind companies (like on-grid solar companies) have long proclaimed their impending competitiveness, as if no one were keeping score.

And with the impending expiration of the federal Production Tax Credit (it has been extended eleven times since it first expired in 1999), distress calls are being heard from familiar quarters.

Old Wind Power

A simple review of Wikipedia’s History of Wind Power refutes the infant industry argument. “For more than two millennia wind-power machines have ground grain and pumped water,” the entry begins. Regarding power generation,

… wind power found new applications in lighting buildings remote from centrally-generated power. Throughout the 20th century parallel paths developed small wind plants suitable for farms or residences, and larger utility-scale wind generators that could be connected to electricity grids for remote use of power.

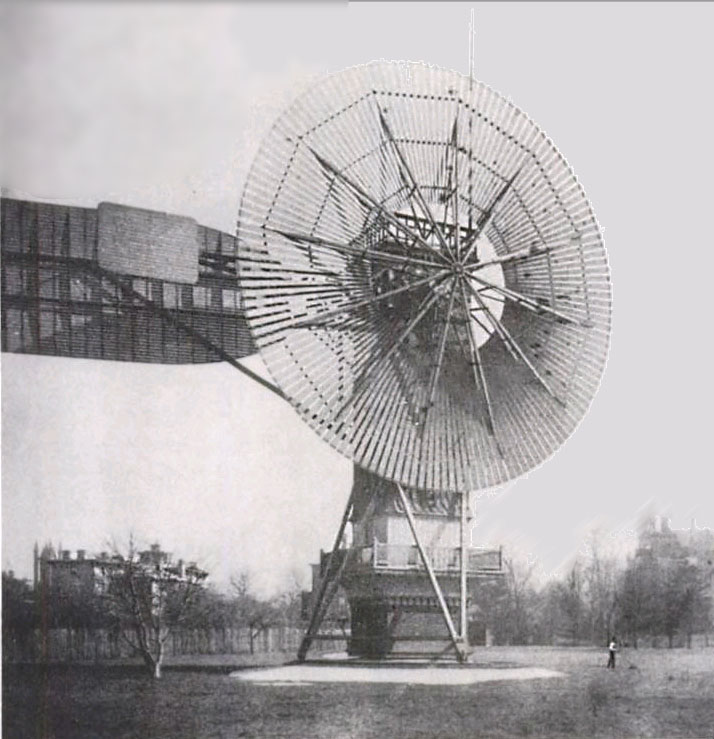

Illustrations of antique generators are provided, such as Charles Brush’s Windmill for (1888) and Grandpa’s Knob Summit (1941).

In the modern energy era, wind proponents have sung the siren song of competitiveness. A consultant representing the American Wind Industry Association (AWEA) testified in 1983 (36 years ago):

The private sector can be expected to develop improved solar and wind technologies which will begin to become competitive and self-supporting on a national level by the end of the decade if assisted by tax credits and augmented by federally sponsored R&D.

Three years later, Michael Bergey of the AWEA testified: “The U.S. wind industry has…demonstrated reliability and performance levels that make them very competitive.”

Other proclamations of competitiveness have been made for decades, summarized here. And just a few years ago, in the heat of a subsidy renewal debate, the same bluster came forth. “America’s wind farms are ready to go it alone,” stated the AWEA last year. Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) similarly declared that wind has “matured as an industry” and was “ready to compete.”

The problem is more fundamental than PR misdirection. The free input of wind is dilute and unreliable, requiring vast amounts of infrastructure (land, steel, fiberglass, concrete, lubricating oils, storage, transmission lines) to produce power. Diluteness and intermittency, now as then, is the curse of industrial wind turbines, as it is for central-station solar panels.

Cronyism Does Not Expire

On-grid solar and wind have turned into crony rivals for market share and the renewable subsidy dollar. “We now have a subsidy arms race,” noted Stephen Moore. Wind complains that solar is getting more government favor, and both complain that competition from cheap natural gas is too great for them to go it alone.

This predicament brings to mind the warning from Milton and Rose Friedman back in 1980 (Free to Choose: p. 49):

The infant industry argument is a smokescreen. The so-called infants never grow up. Once imposed, tariffs are seldom eliminated.

Little wonder that Congress has never let the original Production Tax Credit in the Energy Policy Act of 1992 permanently expire.

Public Policy

The wind PTC, estimated by the U.S. Treasury to cost taxpayers $40 billion between 2018 and 2027 from existing or in-construction projects, should expire for new construction as scheduled. Solar’s Investment Tax Credit (dating from 2005 and extended several times) should not be extended to become the new lifeline for wind power.

Another aged subsidy for wind (and solar) installations, the must-buy provision of the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA), is due for wholesale revision short of repeal to let the market, not federal regulators, shape electrical generation.

The obvious policy is let the consumer decide, a fair-field-and-no-favor environment where taxpayers are not involved. The relatively small remaining subsidies for mineral energies (most of which were repealed in the 1970s) can easily be removed to this end. Free-market neutrality is a natural, easy solution to replace the “all of the above” conundrum where a variety of complicated regulations and tax provisions prop up politically correct energies.