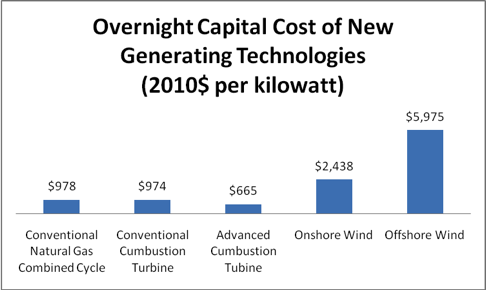

Now that Ted Kennedy is no longer able to halt the Cape Wind project in the waters off of Cape Cod, the Department of Interior has approved the permit that had been moving slowing through the process for the past decade. However, only half of the project’s planned power output has a customer.[i] Why? Wind generated electricity offshore is expensive. According to the Energy Information Administration, the capital cost for an offshore wind unit is two and a half times that of an onshore wind unit, and its operating and maintenance costs are almost twice as much. Compared to a natural gas combustion turbine, the least expensive generating unit, an offshore wind unit’s capital costs are almost 9 times higher.[ii] With costs so much higher, it is not surprising that the developers of Cape Wind are having trouble finding buyers.

Source: Energy Information Administration, Updated Capital Cost Estimates for Electricity Generation Plants, http://www.eia.gov/aer/pdf/pages/sec8_22.pdf

The Cape Wind Project[iii]

Cape Wind was proposed in 2001 as a 468-megawatt wind farm consisting of 130 turbines, each with a maximum capacity of 3.6 megawatts, standing 440 feet tall in the Nantucket Sound, off Cape Cod, Massachusetts, covering 25 square miles.[iv] Because the turbines are to be located more than 3 miles offshore, it is under federal jurisdiction as well as state jurisdiction.[v] The project is estimated to cost $2.5 billion, or over $5,300 per kilowatt. Overall, the project is estimated to have a maximum delivered capacity of 454 megawatts based on a design wind velocity of between 30 and 55 miles per hour.[vi] Based on the average wind speed of the Nantucket Sound of 19.75 miles per hour, however, the average generation capacity of the Cape Wind project would be approximately 182.6 megawatts.[vii] At this capacity, the Cape Wind project would annually deliver about 1,600 gigawatt-hours of energy.[viii]

The project has been opposed by organizations and individuals citing the following problems: hurting views from homes and beaches, lowering of property values, hurting the fishing and yachting industries and marine life, being too close to shipping lanes, privatizing of public property, and ruining ancient religious rituals of the Wampanoag Indian tribes.[ix] Proponents for it argue that it will displace oil and natural gas generation, gain 160 permanent jobs, and create a stable price that would be a hedge against fossil fuel prices.[x]

Buyers and Skeptics

The project has one primary buyer, National Grid, the state of Massachusetts’ largest electric utility, who is slated to purchase half of the output from the project, at a cost of 18.7 cents per kilowatt hour beginning in 2013 and then increasing annually by 3.5 percent in a 15-year deal. That amount is twice what the utility pays for power from fossil fuels and it would add 1.7 percent to the electricity bill of residential customers.

The project has one primary buyer, National Grid, the state of Massachusetts’ largest electric utility, who is slated to purchase half of the output from the project, at a cost of 18.7 cents per kilowatt hour beginning in 2013 and then increasing annually by 3.5 percent in a 15-year deal. That amount is twice what the utility pays for power from fossil fuels and it would add 1.7 percent to the electricity bill of residential customers.

The other half of the project output is up for grabs. The best prospective customer is NStar, the state’s second largest utility, but the company is uninterested because it can purchase renewable energy elsewhere for less and still satisfy the state’s Green Communities Act[xi] and the state’s mandate of obtaining 15 percent of its power from renewable energy by 2020. According to NStar’s spokewoman, “We just want to make sure that we are promoting renewables in the region…but also being mindful of costs for our customers.”[xii] NStar’s 10-year contract with TransCanada, owner of the Kibby Mountain wind farm, for example, is for onshore wind power at 10.5 cents per kilowatt hour.[xiii] NStar, in its recent solicitation for bids from renewable energy generating sources, received 113 bids totaling 9 million kilowatt hours, or 28 times more than it needed to meet state goals next year.[xiv]

Options for Cape Wind

The owners of Cape Wind have two options: either solicit enough buyers to construct the wind farm as planned or scale back the size of the wind farm, increasing the cost to as much as 19.3 cents per kilowatt hour.[xv] Without support from NStar for the other half of the project, it is likely that the Cape Wind owners would need to get buyers from many smaller utilities and government agencies. This difficulty of finding customers for the power is likely to put a damper on other offshore wind power projects being considered off the U.S. east coast.

Onshore Wind

By the end of 2009, the United States had over 35,000 megawatts of onshore wind generating capacity, having added almost 10,000 megawatts in 2009, according to the American Wind Energy Association.[xvi] But, in the third quarter of 2010, only 395 megawatts of new onshore wind capacity had been constructed, the lowest figure for a quarter since 2007. New wind projects through the third quarter in 2010 were down 72 percent from 2009 levels. Part of the reason for the downturn was the expiring renewable tax credit at the end of this year, which was resurrected for an additional year by the passage of the bill extending the Bush tax cuts. Despite the 35,000 megawatts already on line, wind energy cannot make it in the market without government support.[xvii]According to the Energy Information Administration, over 3 times more coal-fired generating capacity and over 3 times more natural gas-fired generating capacity were added in the first 9 months of 2010 than wind generating technology.[xviii]

Another factor in wind’s difficulty to compete against fossil technologies is low natural gas prices sparked by newer drilling techniques that have produced sufficient new natural gas reserves from shale deposits to supply U.S. demand for years.[xix] In the face of these low prices, regulators in several states including Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Rhode Island and Virginia, whose job is to protect consumers from unreasonable rates, have slowed or rejected deals to buy renewable power. In Rhode Island, for example, the public utility commission rejected an offshore wind project that would have cost 24.4 cents a kilowatt hour, compared to 9.5 cents a kilowatt hour for power from fossil fuels. In Kentucky, the public service commission rejected a renewable deal because it would have increased a typical residential customer’s rates by about 0.7 percent.[xx]

Other factors affecting renewable projects are lower demand and tighter loan terms due to the credit crunch. Electricity demand in the United States was down almost 1 percent in 2008 from 2007 levels, followed by a 4 percent reduction in 2009 from 2008 levels. For the first 9 months of 2010, electricity demand was at the same level as in 2009.[xxi] Interestingly, assets are being pulled from renewable funds in favor of conventional energy stocks. European governments that had been into wind and solar projects over the past decade have cut their subsidies for renewable technologies and the Chinese have become competitive in these markets, undercutting their competitors, making renewable funds less lucrative than they had been in the past.[xxii]

Conclusion

Wind energy, though one of the least expensive renewable generating technologies, cannot make it in the market place without government subsidies. This is clearly shown by the decrease in onshore and offshore wind projects in 2010 even though there are mandates in 29 states to generate electricity from renewable technologies. The recession has made utilities such as NStar ever vigilant to keep electricity prices in check and yet meet laws and regulations. Although our politicians recently voted to extend renewable subsidies, those subsidies appear not to be sufficient to support offshore wind development. So, it will be interesting to watch the market dynamics of offshore wind in the future. If it cannot survive in Massachusetts, a state that has one of the highest electricity prices in the country, then where?

[i] Associated Press, Wanted: Buyer for controversial Cape Wind energy, December 19, 2010, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2010/12/19/national/a081715S27.DTL

[ii] Energy Information Administration, Updated Capital Cost Estimates for Electricity Generation Plants, http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/beck_plantcosts/index.html

[iii] For a comparison of the energy output of Cape Wind versus an offshore natural gas well, see https://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/2010/04/14/production-from-developing-manteo-prospect-offshore-north-carolina-vs-equivalent-wind-farm/

[iv] http://www.boemre.gov/offshore/AlternativeEnergy/PDFs/FEIS/Section2.0DescriptionofProposedAction.pdf

[v] Wikipedia, Cape Wind, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cape_Wind

[vi] http://www.boemre.gov/offshore/AlternativeEnergy/PDFs/FEIS/Section2.0DescriptionofProposedAction.pdf

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Wikipedia, Cape Wind, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cape_Wind and Associated Press, Wanted: Buyer for controversial Cape Wind energy, December 19, 2010, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2010/12/19/national/a081715S27.DTL

[x] Ibid.

[xi] http://mastatelibrary.blogspot.com/2010/06/green-communities-act.html

[xii] Associated Press, Wanted: Buyer for controversial Cape Wind energy, December 19, 2010, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2010/12/19/national/a081715S27.DTL

[xiii] Associated Press, Wanted: Buyer for controversial Cape Wind energy, December 19, 2010, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2010/12/19/national/a081715S27.DTL

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] American Wind Energy Association, http://www.awea.org/documents/factsheets/Market_Update_Factsheet.pdf

[xvii] The Wall Street Journal, The Wind Subsidy Bubble, December 20, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703395204576023820064646268.html

[xviii] Energy Information Administration, Electric Power Monthly, Table ES3, http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/electricity/epm/epm_sum.html

[xix] See forthcoming blog post on the Annual Energy Outlook 2011 forecasts, indicating that technically recoverable shale gas resources are estimated to be 2.3 times the level assumed in Annual Energy Outlook 2010.

[xx] New York Times, Cost of Green Power Make Projects Tougher Sell, November 7, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/08/science/earth/08fossil.html?ref=energy-environment

[xxi] Energy Information Administration, Monthly Energy Review, http://www.eia.gov/mer/pdf/pages/sec7_5.pdf

[xxii] Bloomberg, Black Rock Blames Credit Crisis For Clean Energy Fund Outflows, December 24, 2010, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-12-24/blackrock-blames-credit-crisis-as-record-outflows-hit-clean-energy-funds.html