The Center for American Progress (CAP) released a study entitled “Regional Energy, National Solutions” that purported to give “A Real Energy Vision for America.” We here at the Institute for Energy Research (IER) posted a critique of their study on our blog. Needless to say, the folks at CAP weren’t happy with us and responded in turn. In the present post, we’ll deal with CAP’s counterattack and point out that they still haven’t justified their case for bigger government, and less of the market, in the energy sector.

“Finite” Domestic Resources a Strawman?

The first rhetorical strategy CAP uses is to claim that our critique misrepresented them. They write:

One easy response would be to simply point out the institute’s failure to even acknowledge the reality of climate change. Ignoring the fact that our report consistently points to climate change as the most important reason to transition to a cleaner energy future, the institute pretends that we’ve instead written a paper about the world running out of oil.

We didn’t “pretend” anything—what made the original CAP press release so amazing, is that (unlike other proponents of more government intervention in the energy markets) the folks at CAP did indeed stress the fact that the U.S. would eventually run out of fossil fuels. Look at what they wrote:

And ultimately, [the strategy of drill-baby-drill] a mirage. The United States cannot achieve lasting energy and economic security through resource extraction alone. An energy plan based solely on drilling and mining for more and harder-to-reach fossil fuels squanders the opportunity to diversify and strengthen our economy, threatens our nation’s ability to lead in the global marketplace, and completely ignores the urgent need to combat climate change and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels. [Bold added.]

In that paragraph above—where the CAP team first explains to its readers why the agenda allegedly pushed by the nefarious corporate interests won’t work—CAP lists several objections. The first reason they list is that “drilling and mining for more and harder-to-reach fossil fuels” is a mirage. The third thing they mention is climate change.

Later on, in the first bullet point outlining their (allegedly superior) vision, the CAP team wrote: “Recognizes that our earth is warming, and our resources are finite, which means we must swiftly enact measures to make us global leaders in the face of that reality” [bold added].

To give one more example, later on the CAP team writes:

This paper does not disregard the role of fossil fuels in the U.S. economy. It instead looks beyond the finite contributions that fossil fuels can ultimately make to our nation’s energy security and economic prosperity. [Bold added.]

So this is hardly something we invented. The CAP team clearly wants the public to think that relying on domestic extraction of coal, oil, and natural gas is a losing strategy, since we will eventually run out of those “finite” resources.

If the folks at CAP are now agreeing with us, that the “finite resources” argument is not at all a good argument—since North America has literally centuries’ worth of these resources left at current rates of consumption, plus we are always finding more—then we are glad we have built consensus. We just hope to avoid confusion, the CAP team no longer stresses the “finite contributions” from such resources in the future, lest the innocent public draw the wrong conclusion.

Oil vs. Renewables: Who Gets More Federal Subsidies?

Next the CAP response addresses our central argument that coal, oil, and natural gas companies are profitable, providing net tax revenues to the U.S. government. In contrast, many renewables projects depend for their very existence on outright cash subsidies, loan guarantees, or favorable tax incentives. To see this, just consider the howls of protest from the wind lobbyists over the expiration of the Production Tax Credit (PTC). They are quite adamant that without the PTC, thousands of wind-related jobs will be lost and that new capacity will collapse.

To rebut our claim, CAP cites a particular study from TR Rose Associates and concludes: “The federal government’s commitment to supporting the oil and gas industry every year is about 3.5 times greater than its commitment to the renewable and biofuel energy industries.”

There are all sorts of ways one can define “subsidy” and “renewable,” and the time of analysis can vary. We’re not saying, therefore, that the TR Rose Associates analysts are just making numbers up, but we are saying that they’ve reached the opposite conclusion from the Energy Information Agency’s own analysis. It found (see Table ES2) that in fiscal year 2007, the total federal subsidies to coal, natural gas, and petroleum liquids were about 17 percent higher than federal subsidies to renewables, but this was because of a temporary, special program for “refined coal” that was not available beyond 2007. The EIA report also looks at fiscal year 2010, and reports that the total federal subsidies to renewables were now 251 percent higher than the subsidies to coal, natural gas, and petroleum liquids.

Yet there’s more to the story. Looking merely at “total subsidies” to particular sectors of the energy market can be misleading, because relatively little domestic energy is produced via renewables. When we instead ask the question of how much does the federal government subsidize different energy sources per BTU of output, then the comparison isn’t even close. To see just how drastic this adjustment can be, we can turn to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) study that shows in 2009, the federal government gave up $1.97 in tax revenue per million BTUs due to subsidies for renewable energy. In contrast, the government gave up just 4 cents per million BTUs for fossil fuels. Thus, the federal support for renewables in terms of actual energy output was about 49 times greater in 2009 than federal support for coal, oil, and natural gas.

Infant Industry?

Perhaps recognizing that their claims of an imbalance of federal subsidies for coal, oil, and gas versus renewables must look at the past—since even in gross total terms (let alone per BTU), renewables get more subsidies under the Obama Administration—the CAP team writes:

There’s a reason the oil-and-gas industry got subsidies 100 years ago, and it’s the same reason the renewable energy industry gets them today: When a country is in the midst of transforming its energy sector, it needs to support its new and emerging companies.

This claim is dubious for two reasons. First, it simply is not true that the coal, oil, and natural gas sectors “needed” federal subsidies in order to prosper. Here’s the actual history:

The commercial oil industry dates to 1859, the year of the Drake well in Pennsylvania. The U.S. petroleum industry matured in the next decades and then shifted to the southwest with the discovery of the Spindletop gusher in Beaumont, Texas in 1901.

Meanwhile, a commercial petroleum industry developed abroad, a development that would lead to increasing oil imports to the U.S. and price “demoralization” for domestic producers by the late 1920s. From this period through the 1960s, the “problem” was too much oil, not too little.

Does this sound like an infant industry? Hardly…

So when did government oil and gas subsidies begin in the U.S.?

Corporate taxation began in 1909, and the depletion tax writeoff began in 1913. The intangible drilling and development cost deduction began in 1917. So the classic subsidies cited by renewable apologists began a half-century after the industry was born. Direct government subsidies, such as checks written on the U.S. Treasury, were virtually nonexistent in the history of the petroleum industry.

There’s a second flaw with CAP’s argument from history. They are making it sound as if federal support for renewables began last Thursday, and we just need to give it a chance to “take.” Yet for the last 30 years, the proponents of wind and solar power have been arguing that they just needed a little gentle push from Uncle Sam, and that their self-sufficiency was just around the corner.

The Flaws With “Green Jobs” Accounting

Above, we’ve pushed back on some of the peripheral claims and arguments put forward by the folks at CAP. Yet now let’s take on one of their central arguments: They claim that their “vision for America” is better than the shortsighted strategy of relying on further exploitation of coal, oil, and natural gas, because the CAP approach will create vast numbers of “green jobs” all over the fruited plain. Indeed, the bulk of their study consisted of regional analyses showing the number and types of renewables jobs spurred by wise government investments in various states.

In the first place, the CAP analysis commits the familiar flaw of thinking a “job” is good per se, as opposed to the flow of goods and services. In the classic refutation of this logic, we can imagine the government paying a million workers to dig ditches, and another million to fill them back up. This would “create 2 million jobs” all right, but that would hardly be an indication of economic efficiency.

The market economy, with its price system and associated signals of profit and loss, is perfectly capable of “creating jobs” in the right sectors according to resource supplies, technological know-how, and consumer demand. As we stated in our original critique, the CAP study moves far beyond the correction of an alleged “negative externality” from greenhouse gas emissions, and is instead engaged in outright central planning: picking winners and losers and talking about quantifiable job creation in specific areas of the country.

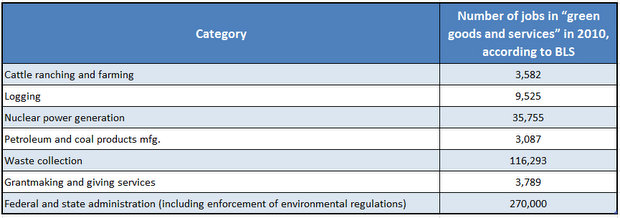

Yet beyond the fundamental misconception of the “green jobs” premise, is the fact that in practice these estimates and what gets defined as a “green job” can be absurd. In a previous post, we discussed the hilarious accounting that the Bureau of Labor Statistics used in its new “green goods and services” index. Of the impressive 3.1 million “green goods and services” jobs in 2010 meeting the BLS’ criteria, we found the following entries:

What About Climate Change?

What of the potential threat of climate change from greenhouse gas emissions? Well, even on its own terms, the textbook argument about a negative externality implies only the need for a corrective “carbon tax”—and that’s it. Yet the CAP study goes far beyond such a call. For example, its second bullet point explained that the CAP vision for America “[m]andates investment in multiple forms of energy and fuel so we are never dependent on just one finite resource for electricity and transportation needs.” It is this type of policy recommendation and mindset that led us to declare the CAP authors as “central planners.” There are plenty of conventional environmental economists who believe climate change is a real threat, and yet call for a simple carbon tax because they actually take their own claims of a simple “externality” seriously. If the problem with the market outcome is a negative externality, then a simple tax would fix it.

Of course, readers of this blog know that IER does not endorse the conventional argument for a “negative externality” and the corresponding calls for a carbon tax (or a cap-and-trade program). Here is a peer-reviewed journal article outlining the numerous problems in the conventional case for a carbon tax, and here is a more recent blog post explaining the dangers in the arguments that a “revenue-neutral” carbon tax could boost the economy.

Do the American People Want to Pay for CAP’s Vision?

The CAP team is on very shaky ground when it writes:

All these success stories, combined with the simple fact that clean energy helps slow climate change, help explain why the American public—those same taxpayers that the Institute for Energy Research cares so deeply about—overwhelmingly supports a move toward a cleaner national energy system. In fact, Harvard and Yale researchers find that the average American is willing to pay $162 per year more to support a national clean energy standard, which is just one policy we recommend in our report.

This study begs the question, if people are “willing to pay” $162 per year for a national clean energy standard, then why is a national clean energy standard needed in the first place? If people will voluntarily pay more money for renewable programs, then there is no need to mandate renewable purchases. But the reality is that even in places like Austin, Texas the adoption rate for voluntary renewable electricity programs can be low.

Also, we must be very careful in discussing what the “average American” would be willing to pay, because there are different types of averages. The particular study linked by CAP for the above quotation is designed in such a way that the median and mean willingness to pay are equivalent (as the study’s contact author confirmed via email). This doesn’t make the results “wrong,” it just makes them potentially misleading to the unsuspecting reader.

To see just how significant this subtlety can be, consider a survey of 1,000 likely voters conducted in April 2012 by MWR Strategies. Here was question #20 along with the results:

How much more would you personally be willing to pay each year to make the economy less dependent on fossil fuels overall? I just need a number in dollars.

MEAN: 429.1

MEDIAN: 1

Thus, CAP is correct if it wants to argue that there are some Americans who are willing to pay the higher energy prices that CAP’s policies would entail. However, at least according to the surveys with which we are familiar, the majority of Americans don’t want to pay significantly higher prices, or more in taxes, to achieve the type of energy transformation envisioned by CAP.

Conclusion

In terms of economic theory, political history, and the voting preferences of the American public, the CAP vision for America is itself unsustainable. It claims to want to deliver reliable energy, create jobs, and reduce American dependence on hostile regimes. The easiest way to achieve all of these goals is for the federal government to get out of the way and let entrepreneurs develop domestic resources. If it makes economic sense, those “domestic resources” may some day include a large expansion in wind, solar, and other renewable technologies, but the private capital markets should make that decision, not the scholars at CAP.