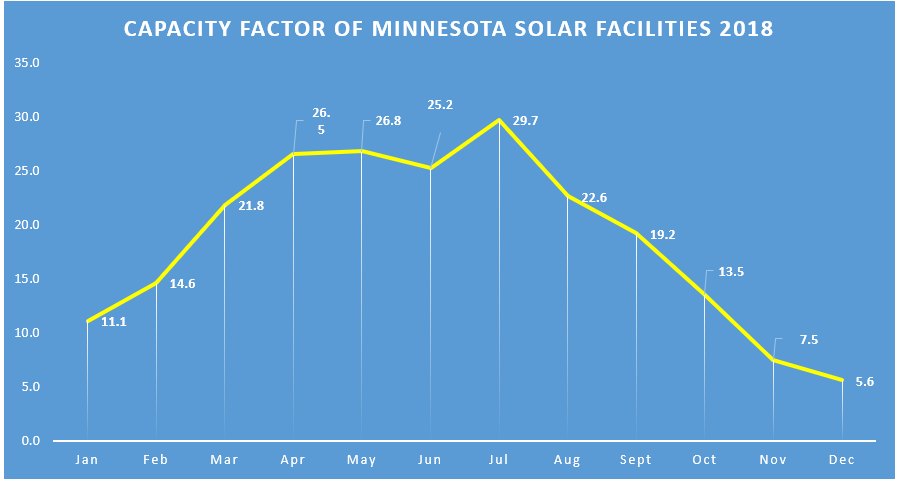

Data show that solar panels do not work well during Minnesota winters. Solar panels generated nearly 30 percent of their potential output in July of 2018 in Minnesota, but electricity generation from the state’s solar plants dropped to 5.6 percent by December 2018. Reasons for the performance decline—which only politicians and interest groups could find surprising—include shorter days during winter, performance of solar panels lessened from snowfall because snow reflects light, and the expense to clear snow off of solar panels.

It is expensive to clean snow off solar panels, especially at large solar arrays where thousands of panels are spread over acres of land. Snow removal without human intervention can sometimes be achieved by single access tracker panels that can be tilted to optimize performance, but those panels generally cost more than traditional fixed panels. Fixed, low pitch panels work well in the warmer half of the year because they pick up light for longer periods. There is less production with shallower pitch solar panels in winter, but those panels generally make up for the loss in summer. Snow also adds weight to panels and can cause microcracks, especially on panels enclosed in frames, which are the most widely used modules today.

Issues Arising from Federal Subsidies and State Mandates

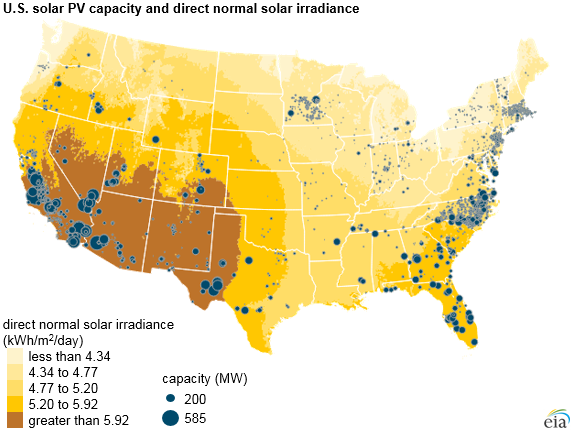

Minnesota and other states are building solar arrays due to federal subsidies and state government mandates. In 2013, the Minnesota legislature passed the Solar Energy Standard, which mandated that 1.5 percent of the state’s electricity must come from solar energy by the end of 2020. Despite Minnesota’s poor solar resources depicted below, Xcel Energy wants to spend billions of dollars building 4,000 megawatts of solar power not because it is the most productive way to generate electricity, but because it will obtain the most government-guaranteed profits. The solar plants will replace reliable coal plants, which will be closed a decade early.

Using the cost estimates to build solar photovoltaic technology from the Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook 2020, building these solar panels would cost $5.4 billion, without federal subsidies. The federal investment tax credit (ITC) for solar is currently a 26 percent deduction on the capital cost of installing a solar energy system from federal taxes. In essence, federal taxpayers will pick up 26 percent of the capital cost of solar panels, or $1.4 billion of Xcel’s costs, if the solar farm is built this year. In 2021, the ITC is reduced to 22 percent of the cost of the solar system, and after 2021, the ITC is reduced to a permanent 10 percent of the cost of commercial solar systems.

State Renewable Portfolio Standards

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia (DC) have renewable portfolio standards (RPS)—polices that require electricity suppliers to supply a specified share of their electricity from designated renewable resources or eligible technologies by a certain date. While publicly sold as “standards,” they are mandates. Although no additional states have adopted an RPS policy since Vermont in 2015, several states have extended their existing targets in 2018 or early 2019, continuing a trend in recent years across the United States. States with legally binding renewable portfolio standards collectively accounted for 63 percent of electricity retail sales in the United States in 2018. In addition to the 29 states with binding RPS policies, 8 states have nonbinding renewable portfolio goals. Since utilities are a highly regulated industry, such goals are always potentially up for discussion when non-renewable permits are required from the state or local government.

Solar Losing Its Aura in New England

In Connecticut, an 18-megawatt solar project that would help the state meet its RPS has been in the blueprint phase for three years. Local environmental and neighbor groups believe the proposal will lead to runoff and environmental degradation and want regulators to reject it. In New England, forests have been cleared and hilltops leveled to make way for new solar arrays. Environmentalists indicate that the soil on hilltops and sides is thinner from natural erosion, and when graded for solar arrays, it becomes more vulnerable. In Connecticut, environmental officials have issued cease and desist orders in recent years to owners of three solar projects that have led to adverse water quality impacts.

Conclusion

Solar power is not always beneficial, particularly in certain northern U.S. states where solar irradiance is not the best. In Minnesota the capacity factor of solar fell to 5.6 percent in December 2018, the time of year when it is darkest and cold weather begins to set in. Solar power loses its performance value due to shorter days in winter, snowfall reflecting light, and the expense of removing snow from solar panels. Solar energy is being pushed due to state renewable performance standards and federal tax credits, which will fall to a permanent 10 percent reduction after 2021 unless extended by Congress. However, some states are losing interest in solar power due to environmental concerns when forests need to be cleared and hilltops leveled to make room for solar panels. It appears that as more is learned about solar energy, more questions are being generated, even when electricity from solar panels is not.