The American Wind Energy Alliance (AWEA) has a snazzy PDF showing the importance of the Production Tax Credit (PTC) to the maintenance of the wind sector. Yet in so doing, AWEA has unwittingly made the same case we’ve been making for years: The federal government is artificially propping up the entire wind sector through the tax code. AWEA’s own charts and statistics demonstrate that the wind sector wouldn’t be nearly as big as it currently is, if we had a level playing field where the government didn’t pick energy winners and losers.

We have previously written summaries of the history of the PTC for wind and other renewable energy initiatives. In this post, we’ll just walk through the AWEA’s own document, to show that they actually agree with our perspective—yet somehow derive the opposite conclusion from it.

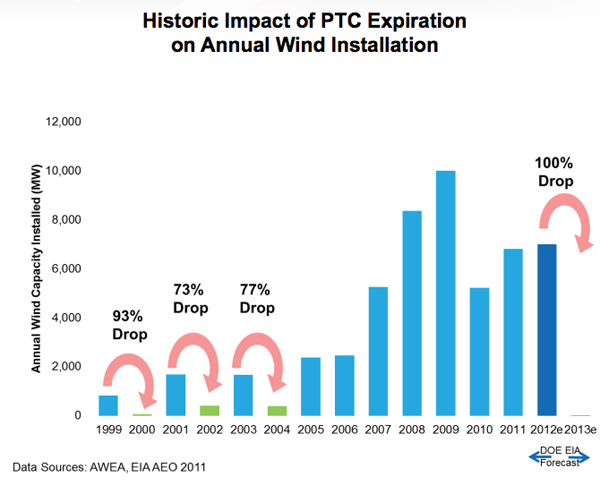

First, consider their bar chart showing the impact of (temporary) expirations of the PTC for wind in the past:

As the chart clearly demonstrates, increases in wind capacity are virtually entirely the creature of federal tax advantages. Take away the lopsided treatment of wind versus other energy sources of electricity (such as coal), and the industry stops building more wind capacity.

One reason why new wind capacity is dependent on federal tax advantages is because the PTC is rather generous. The PTC pays 2.2 ¢/kWh,[1] but that is after taxes. The PTC is worth a pre-tax value of about 3.7 ¢/kWh (assuming a 40% marginal tax rate).[2] To put that in perspective, the price of electricity for industrial users in much of the United States is less than 6.5 ¢/kWh[3] (and the wholesale price is obviously lower). A subsidy which is such a large part of the cost of electricity leads to some perverse outcomes. For example, during periods of low demand, and high wind, wind producers can make money by paying the electricity grid to take their electricity. As long as the wind producers only pay a couple of cents per kWh, they will more than recoup their losses through the PTC.

There’s another interesting point: This is a long-term dependency problem for wind. It’s not as if wind proponents can claim their technology needs just a little nudge from the federal government to jump out of the nest and take flight under its own power. No, the dependency (by their own chart) goes back more than a decade, and indeed the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for wind started back in 1978. The proponents of wind, solar, and other alternative power sources often make it sound as if self-sufficiency is just around the corner, but shucks in practice that corner keeps receding.

The AWEA sheet next informs us that a typical wind project “requires 18 months of policy certainty,” illustrated by the following:

To reiterate, by “policy certainty” they mean, “Knowing that the federal government will tax competitors of wind at a higher rate.” This particular chart makes it seem as if the “infant industry” argument is valid, and that the wind lobbyists are just asking for a year-and-a-half of help. But it’s not so surprising that a wind project can operate once it’s been built in an environment of tax advantages. Obviously when considering the economic efficiency of a particular power generation technique, the major costs will come in the beginning, during construction and assembly. Once the system is up and running, it had sure better have a large margin of “profit” considering just the revenues versus the operating costs.

Finally, the AWEA sheet warns of “Projected Job Losses in U.S. Wind Industry as PTC Expires” (referring to the looming expiration at the end of 2012), accompanied by the following:

The general pattern of the above chart is no doubt true. But is this surprising? If the federal government has been giving artificial tax advantages to an industry, and then allows those advantages to lapse, then yes the industry’s output and employment will shrink.

Yet this would be true for any product or service, not just wind turbines. The fact that workers and other resources would flow out of wind—and into other sectors—doesn’t tell us whether this would be a good or bad thing. For that, we need a broader economic framework. And that broader framework tells us that decentralized markets are a superior way of allocating resources than having policymakers in Washington D.C. pick winners and losers.

In conclusion, let’s address one final point: As a free-market think tank, shouldn’t IER support AWEA’s claims about onerous tax burdens hurting job creation? Yet the issue here is one of uneven taxation. If the federal government kept the PTC for wind, but also gave similar tax credits to fossil fuels, then once again we would see the wind sector collapse, and workers would flow out of it into other sectors. Thus the issue isn’t high or low taxes on wind per se, the issue is that the wind proponents need lower taxes on wind than on anybody else.

Ironically, the AWEA’s own graphs and statistics make the case that IER has been advancing: The Production Tax Credit for wind is an artificial tool by which the federal government maintains a bloated wind sector. If the government wants to lower tax burdens on business to fuel job growth, it would be more efficient to give a broad-based reduction in marginal rates, rather than picking specific technologies and granting them exemptions from the tax burden imposed on their competitors.

[1] DSIRE, Renewable Electricity Tax Credits (PTC), http://dsireusa.org/incentives/incentive.cfm?Incentive_Code=US13F.

[2] Lisa Linowes, Testimony before the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, April 19, 2012, http://science.house.gov/sites/republicans.science.house.gov/files/documents/hearings/HHRG-112-SY21-WState-LLinowes-20120419.pdf

[3] Energy Information Administration, Table 5.6.A. Average Retail Price of Electricity to Ultimate Cusomters by End-Use Sector, by State, May 2012 and 2011, Electric Power Monthly, July 26, 2012, http://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.cfm?t=epmt_5_6_a.