There were 7 aluminum plants in the United States two years ago, but 3 of those have shuttered, leaving the country with only four. The third aluminum plant was shuttered in Southeast Missouri in January–a plant that had the capacity to produce as much as 30 percent of the country’s overall supply of aluminum—due mainly to increasing electricity prices that represent about 40 percent of the plant’s cost. Smelting, which takes refined bauxite ore and converts it into the lightweight metal that is usable in commercial products, requires near-constant electricity at high volumes. Another aluminum smelter — a Century Aluminum plant in Hawesville, Kentucky — shut down in June 2022 after power costs had tripled, making operations unsustainable.

The Missouri plant, Magnitude 7 Metals, was the state’s single largest consumer of energy. According to company executives in a letter to employees, “abnormally cold weather” and unforeseen “business circumstances” were behind the decision to close in January. But local officials said that high energy costs contributed to the plant’s difficulty.

Aluminum is the world’s second-most used metal behind iron. Aluminum is used in everything from airplanes and cars to solar panels and electric transmission lines. The International Energy Agency (IEA) said in a 2021 report that aluminum was among the most important critical minerals for the energy transition, in large part because of its relative light weight and low cost. The material has been used to make cars and electric vehicles lighter and accounts for 85 percent of solar panel components, predominately in frames and inverters. Clearly, the metal is important to Biden’s clean energy program. And, the closures are surprising given Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act that is designed to increase supplies that are needed for the clean energy transition and create a domestic supply chain for clean energy products. The law has tax incentives for sourcing materials domestically, but as electricity prices rise in the United States, domestic producers suffer.

To build the transmission lines and solar panels necessary for a clean energy transition, the United States needs more aluminum. To make that aluminum, the country needs more cheap and reliable power that China has built and continues to build and operate from coal plants. But state-of-the-art coal plants cannot be built in the United States due to onerous regulations, and building natural gas plants will also become a problem when EPA’s power plant rule is finalized next month, as well as operating existing coal plants. EPA will wait and rule on existing natural gas plants after the election due to criticism from utility companies that the reliability of the electric grid would be endangered without them. Utilities worry about the reliability of the grid as more intermittent renewables are forced into the system and incentivized as in the Inflation Reduction Act.

U.S. Lost Its Leadership Role in Aluminum Production to China

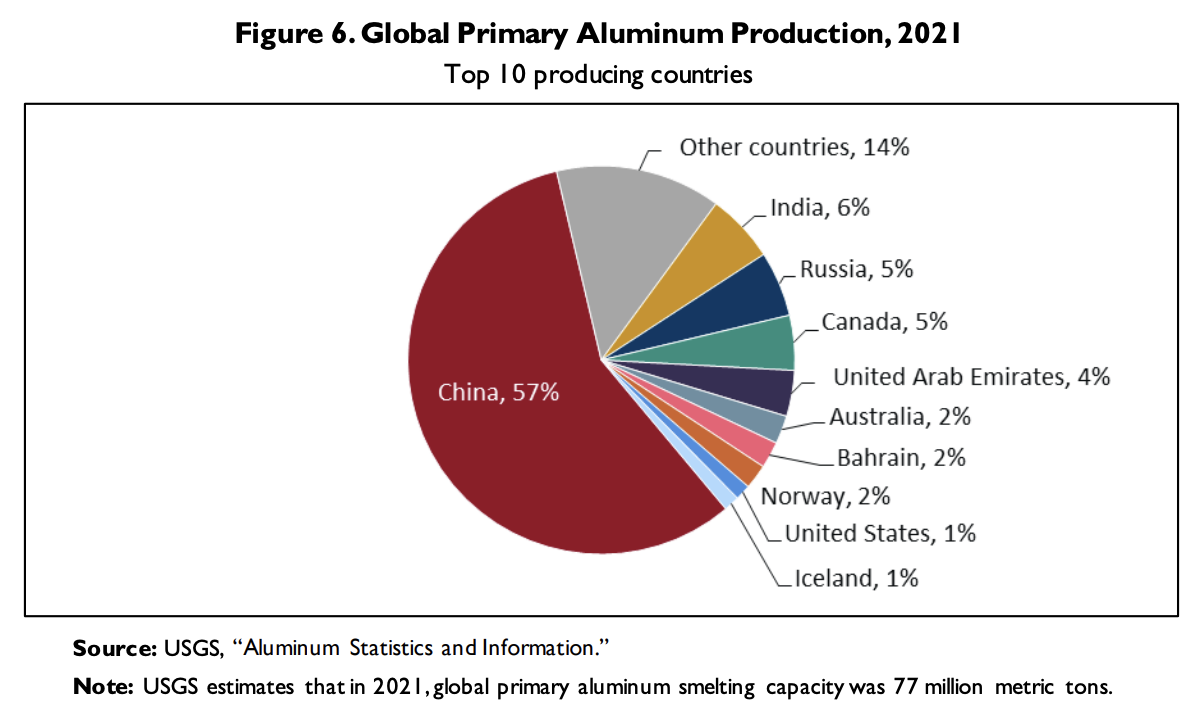

The United States was the top producer of aluminum through 2000. At its peak in 1980, the industry produced 5.1 million metric tons, according to the Congressional Research Service. But by 2021, that production was down to just 880,000 tons—a decline of 83 percent. In 2021, the United States consumed 4.3 million metric tons, meaning the United States must import most of its aluminum needs. In 2022, the United States imported 35 percent of its aluminum imports from Canada and 11 percent from China ($4 billion)—the two largest importers to the United States. The global aluminum sector has seen major changes over the last two decades with China’s rise to be the leading producer in most segments of the aluminum value chain. With China producing almost 60 percent of the world’s aluminum, concern is mounting due to the importance of aluminum to the “green energy” supply chain.

Running smelters, which produce aluminum, is an energy-intensive operation. A World Economic Forum report estimated that aluminum accounted for 2 percent of the world’s human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Actions to Save the Missouri Plant

The Magnitude 7 plant in New Madrid, Missouri, had been closed before, was bought from bankruptcy and restarted after the Trump administration had imposed duties on imported aluminum from China in 2018. Even in 2020, however, the plant was “seeing red numbers every month.”

Last year, Missouri lawmakers passed an $8.5 million loan for the plant in the state budget, but it was vetoed by Missouri Governor Mike Parson amid questions about its constitutionality. Another bill proposed this year by gubernatorial candidate and state Representative Crystal Quade would allow a third-party renewable generator to generate electricity and sell it directly to the aluminum smelter. The bill has not advanced and intermittent energy is unlikely to meet the full-time needs of a large consumer.

In January, Senator Josh Hawley sent a letter to President Joe Biden asking him to invoke the Defense Production Act of 1950 to prevent the plant’s shutdown, which would “preserve good-paying union jobs and safeguard national security.” That law gives the president the ability to require companies to take actions in the national interest and was invoked last year by Biden to address a nationwide baby formula shortage. The White House has not responded to the letter.

The plant relies on relatively high-cost coal from the local utility Associated Electric Cooperative Inc. (AECI) as U.S. regulations require all sorts of expensive emissions controls on coal plants that plants in China do not mandate. Other smelters have the benefit of being located near cheaper sources of electricity. The Alcoa Massena plant in upstate New York has a hydroelectricity contract with the New York Power Authority. Century Aluminum’s Mount Holly plant in South Carolina has struck three-year power contracts with a local power provider where 55 percent of the state’s electricity comes from 4 nuclear power plants and natural gas and coal supply most of the remainder.

In December 2023, Biden’s Treasury Department announced proposed regulations implementing the Section 45X tax credit for domestically produced goods. The Treasury’s proposal applied the tax credit to aluminum production, which would provide a $60 million benefit in 2024 and up to $50 million more if the credit could apply to direct and indirect material costs. The credits would help to underpin further investment in the industry, strengthen domestic supply chains and ensure that the U.S. industry will be able to meet U.S. needs for the metal. The Treasury Department, however, is still finalizing the tax credits. Policy action from the incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act is not happening fast enough to change the economics for the industry. The result is that just two of the country’s smelters are running at full capacity and production continues to drop.

Conclusion

The U.S. aluminum industry is down to just 4 plants with only two running at full capacity due mainly to high electricity costs that have resulted from onerous regulation and heavy incentives for renewable plants, particularly for wind and solar power. Most recently an aluminum plant in Missouri has shuttered. Local politicians are trying to get it reopened as the metal is important to the country’s “clean” energy program mandated by President Biden. But without cheaper energy, it’s going to be harder to make that metal at home and get more “clean energy” on the grid. Unfortunately, it is a catch 22 because forcing wind and solar upon the grid is causing electricity prices to increase as they cannot operate 24/7 and need backup power, which is costly. China is now the major global producer of aluminum and the United States will likely be importing more from China over time.