Last week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its Energy Technologies Report . In the report, IEA estimated that cutting carbon dioxide levels in half by 2050 would cost $45 trillion. While reports like this are always based on a number of assumptions, one very important assumption in this case is the amount of “spontaneous decarbonization” of world’s economy. If there is 10 percent less spontaneous decarbonization than IEA projects, reducing carbon dioxide levels will be an additional $21 to $53 trillion. If there is no spontaneous decarbonziation, reducing carbon dioxide concentrations in half will cost between $255 trillion and $545 trillion.

What is “spontaneous decarbonization”? In order to estimate the costs of reducing carbon dioxide levels, among other things, IEA estimated carbon dioxide emissions over time, technological change, and improvements in energy efficiency. Improvements in technology and energy efficiency reduce the amount of energy (and carbon dioxide emissions) required to produce the same amount of work. For example, from 1990 through 2000, the U.S. used 1.6% less carbon dioxide per dollar of GDP per year. That’s a pretty impressive improvement.

By improving our energy efficiency through technological innovation, the economy of the U.S. has experienced some “spontaneous decarbonization.” You can call this spontaneous decarbonization because it happened without programs like cap-and-trade or a carbon tax.

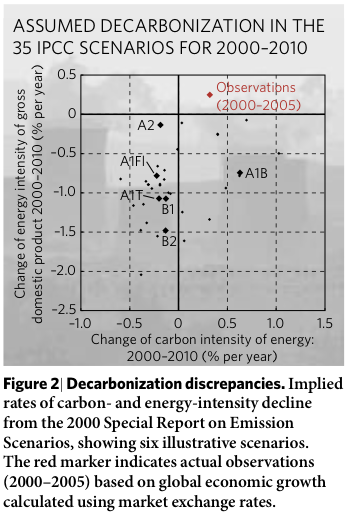

Why do estimates of the rate of spontaneous decarbonization matter? Cost estimates such as IEA’s and the IPCC’s (the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) assume that the vast majority of future carbon dioxide reductions come from spontaneous decarbonization and not programs like cap-and-trade. In an article in Nature , Roger Pielke Jr., Tom Wigley, and Christopher Green calculate that in the IPCC’s reference scenario, 77% of the carbon dioxide reductions needed to stabilize atmospheric carbon dioxide levels at 500 parts per million would come from spontaneous decarbonization of the economy. Only the remaining 23% would require explicit policies such as carbon taxes or cap-and-trade.

What if estimates of the rate of spontaneous decarbonization are wrong? Roger Pielke Jr., at the Center for Science and Technology Research at the University of Colorado, Boulder, calculates that if we don’t assume there will be spontaneous decarbonization, reducing carbon dioxide concentrations in half will cost between $255 and $545 trillion. This is far more than IEA’s estimate of $45 trillion.

An Unpredictable Future. If one looks at the decarbonization of the U.S. economy, it seems safe to project sponteanous decarbonization into the future. But this might not be the case everywhere in the world or for the world as a whole. According to Pielke Jr., Wigley, and Green:

the IPCC assumptions for decarbonization in the near term (2000-2010) are already inconsistent with the recent evolution of the global economy (Fig. 2). All scenarios predict decreases in energy intensity, and in most cases carbon intensity, during 2000 to 2010. But in recent years, global energy intensity and carbon intensity have both increased, reversing the trend of previous decades.

Figure 2 above is from Pielke Jr., Wigley, and Green’s paper in Nature. It shows that the observations from 2000-2005 buck the global trend of lower energy intensity per unit of GDP.

Will this continue into the future? No one knows. If it does, it will cost far more than IEA’s estimate of $45 trillion to cut carbon dioxide levels in half. Because the future is unpredictable, we should pay close attention to Pielke Jr, Wigley, and Green’s conclusion:

There is no question about whether technological innovation is necessary—it is. The question is, to what degree should policy focus directly on motivating such innovation? The IPCC plays a risky game in assuming that spontaneous advances in technological innovation will carry most of the burden of achieving future emissions reductions, rather than focusing on creating the conditions for such innovations to occur.