The White House unveiled a framework to provide $5 billion to states to expand their electric vehicle charging networks toward President Biden’s promise to build 500,000 charging stations by the end of the decade to help achieve his goal of having half of all new vehicle sales by 2030 be electric. The Department of Transportation (DOT) has asked the states to provide plans to the federal government before receiving the money. The framework calls on states to prioritize building charging infrastructure on interstate highways under the Transportation Department’s alternative fuel corridors program. If a state does not submit a plan, DOT will award funds directly to local jurisdictions or give the funds to other states. DOT will distribute funds, which were approved by Congress in the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure bill last year, over the next 5 years. The infrastructure bill that Congress passed in November includes $7.5 billion for 500,000 new chargers.

However, drivers of electric cars will have to exit the highway if they rely on the Biden administration’s $5 billion for chargers because federal law limits commerce at interstate rest stops to vending machines, lottery tickets, and tourism promotion. The recent infrastructure law (Public Law 117-58) did not change a 1956 restriction on commercial activity at rest stops. It is an issue that has divided fuel retailers and electric vehicle advocates. The guidance from the Federal Highway Administration says electric vehicle chargers should be as close to the Interstate Highway System and highway corridors as possible and generally no more than one mile from the exit. Some older rest stops are not subject to the Eisenhower-era restriction. This restriction has the potential to force charging infrastructure further off the travel corridor, limiting solutions for planners, increasing range requirements for vehicles, and potentially inconveniencing drivers.

Electric vehicle range has been a major factor for electric vehicle buyers, who often see an electric car as a second vehicle along with owning a gasoline or diesel vehicle that can more easily be used for long distance trips which are common in the United States, the third largest nation by size in the world. U.S. electric vehicle sales have lagged behind other industrialized countries for this reason as well as their higher initial costs and much longer refueling times.

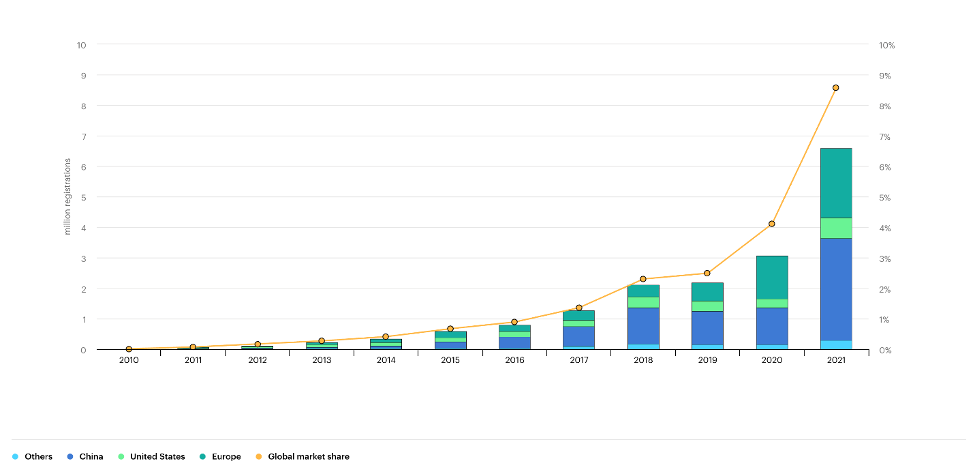

Electric vehicles accounted for almost 9 percent of new cars sold globally last year—up from 2.5 percent in 2019. U.S. electric vehicle sales in 2021 doubled their share to 4.5 percent, surpassing half a million sold. The U.S. electric car market is still mostly dominated by Tesla, which accounts for more than half of all electric units sold. Federal tax credits (except for Tesla and GM vehicles) are still available to U.S. consumers, and Biden and some automakers are pushing to expand and extend them.

Global sales and sales market share of electric cars, 2010-2021

DOT Schedule

DOT will initially deploy an installment of $615 million. All 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico are required to submit plans by the beginning of August, explaining how they would install high-voltage chargers along or very close to major highways. The chargers must be no more than 50 miles apart. States are encouraged to place them at rest areas that allow them, or other places with food and other services, which makes them more convenient because of the long recharging times. Federal officials will decide by the end of September whether to approve the states’ plans. The administration hopes the private sector will also add charging stations, but plans to spend $2.5 billion on chargers in rural areas or other communities where private sector operators may be less inclined to invest. There are currently fewer than 50,000 public charging stations in the United States.

Biden sees the charger plan as a way to create jobs for electricians and other workers and a way to revive manufacturing in the United States. Tritium, an Australian manufacturer of charging equipment recently announced plans to build a factory in Lebanon, Tennessee, that is expected to eventually produce 30,000 chargers per year, employing 500 people.

Issues with the Electric Vehicle Transition

One issue is the type of charging station that will be provided. There are currently three different types, or levels, of electric vehicle chargers. Level 1 chargers plug into a regular 120-volt power outlet and deliver power to electric cars at three to five miles of range per hour, which could take tens of hours to charge a 100 percent electric car. Level 2 chargers require 240 volts, charging cars around 10 times faster than Level 1 chargers and bringing a battery to full charge within a few hours. Level 3 chargers, called DCFC fast chargers, are the fastest and most expensive, adding anywhere from three to 20 miles of range per minute. But not every electric vehicle can charge using level 3 chargers. Also, charging at a DCFC station is only effective if the battery’s state-of-charge is below 80 percent.

Because electric vehicles have fewer components than gasoline vehicles, electric vehicles require far fewer workers to build them. As a result, there will be job losses at auto manufacturers and suppliers. Makers of mufflers, fuel injection systems and other parts could go out of business, leaving these workers jobless. Nearly three million Americans make, sell and service cars and auto parts. Americans losing these jobs need to find employment elsewhere.

The electric vehicle transition could also be limited by the lack of battery metals like lithium, nickel and cobalt, which could become more sought after than oil. Prices for these materials are skyrocketing, which could limit electric vehicle sales in the short term by driving up the cost of electric cars even more. Further, China dominates the battery supply chain, making the United States dependent on them for the critical metals needed for batteries. And, adding charging stations at or near highways may help some potential buyers but it does not help apartment residents or street-parking homeowners who cannot charge at home.

Conclusion

The $5 billion, to be spent over five years, will not be nearly enough to build the charging network that is needed to meet Biden’s goal for a fleet of electric vehicles. Despite that, administration officials hope the federal charger plan will encourage utilities and private operators to build additional chargers to aid in Biden’s plan for an electric vehicle transition. But, many other issues remain, including skyrocketing costs for battery metals—an industry that China dominates, high initial prices for electric vehicles, long refueling times, job losses for Americans in the automobile manufacturing and supply industries, and nowhere to recharge for apartment residents. Biden’s plan appears to be to spend taxpayer funds on his wish list without evaluating the feasibility.