In a recent editorial, the NYT argued that we have “proof that a carbon tax works.” By “works,” the editorial board meant that it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions without hurting the economy. However, the one example they give regarding economic effects—British Columbia—actually falls apart under closer scrutiny. Furthermore, even on paper a carbon tax needs to be revenue-neutral to minimize the economic blow, and this is something the NYT board cannot afford in light of their publicly stated spending goals.

Carbon Tax Hurt the British Columbian Economy

The NYT repeats a familiar talking point regarding carbon taxes:

British Columbia started taxing emissions in 2008. One big appeal of its system is that it is essentially revenue-neutral. People pay more for energy (the price of gasoline is up by about 17 cents a gallon) but pay less in personal income and corporate taxes. And low-income and rural residents get special tax credits. The tax has raised about $4.3 billion while other taxes have been cut by about $5 billion. Researchers have found that the tax helped cut emissions but has had no negative impact on the province’s growth rate, which has been about the same or slightly faster than the country as a whole in recent years.

In fact, as my co-authors and I demonstrated in a Cato Working Paper last fall, the impact on emissions is much smaller than researchers originally thought, and the British Columbia carbon tax has apparently hurt its economy.

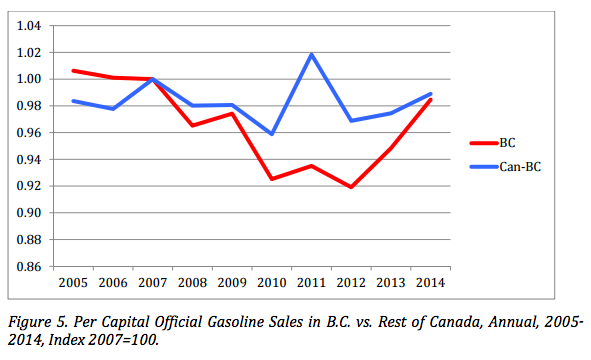

Specifically, Figure 5 in our paper (p. 33) shows that despite an initial plunge, by 2104 per capita gasoline sales in British Columbia had rebounded to about the average of the rest of Canada.

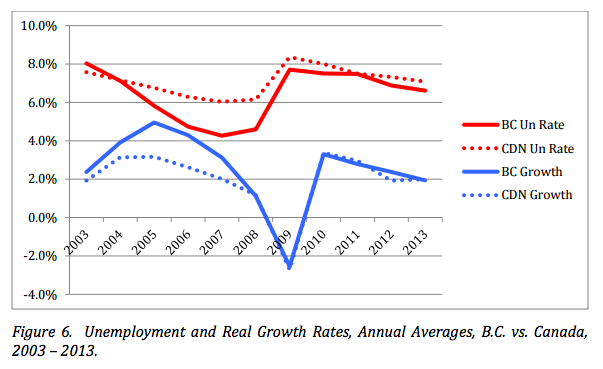

Regarding the economic impact of the B.C. carbon tax, its defenders (including the NYT) keep pointing out that growth in the province has matched the rest of Canada since introduction of the carbon tax (in 2008). But that isn’t the right comparison, because before 2008, B.C. typically grew faster than the rest of Canada. Our Figure 6 shows the true story:

As our Figure 6 shows, B.C. unemployment (solid red line) was lower than the Canadian average (dotted red line) for several years before 2008. Yet after 2008, the B.C. unemployment rate shot upward, tracking the national average.

We see a similar pattern in Figure 6 regarding economic growth. The B.C. growth red (solid blue line) was higher than the Canadian average (dotted blue line) for years before the carbon tax, but after 2008 they were almost identical.

Thus we see that the NYT’s talking point is true but irrelevant. The before-and-after comparison in Figure 6 shows that the evidence suggests the 2008 introduction of a carbon tax hurt the British Columbian economy.

Revenue Neutrality?

It’s worth pointing out that these dire economic impacts on the B.C. economy occurred even though they did a surprisingly good job of implementing offsetting tax cuts. Were a carbon tax to be introduced in the United States, the politics would almost certainly result in a large net tax hike.

For one thing, look at the very examples that the NYT gives us:

Meanwhile, jurisdictions using the cap-and-trade approach like California, the nine Northeastern states and Quebec are investing the revenue generated by auctioning emission permits in mass transit, energy efficiency, renewable energy and other strategies to reduce carbon emissions. Some of the revenue is also dedicated to helping low-income families cope with higher energy costs.

Boondoggle “green” investment projects do not count as “recycling” the revenue back into the economy; instead it is simple tax-and-spend Big Government. Progressives of all people should be wary when political officials hand out money to favored corporations; this is the antithesis of egalitarianism.

Furthermore, although giving targeted relief to low-income families—who are hit hardest by rising energy prices—might make the most sense morally, it is not the way to promote economic growth. Indeed, as I have mentioned earlier on these pages, even the biggest cheerleaders for a carbon tax admit that the only way to get a “double dividend,” where offsetting tax cuts can boost the conventional economy, is to devote carbon tax revenues to cutting taxes on capital. How likely is that? Is the NYT really going to come out in favor of hundreds of billions in tax relief for corporations and hedge fund managers?

Actually, we don’t need to ask that rhetorically. Back in October, the NYT board wrote:

In the next 10 years, revenues will need to increase by 40 percent simply to keep federal spending even, per capita, with inflation and population growth. Additional revenues will be needed to pay for health care for the elderly, transportation systems and other obligations, as well as for newer challenges, including climate change. And interest on the national debt will surely rise because interest rates have nowhere to go but up.

In light of these needs, taxes have to go up. The reality is that income tax increases can be prudently imposed only on the wealthy at this point, because only they have had meaningful income gains in recent decades. [Bold added.]

In light of writings such as these, it is quite deceptive to claim that a revenue-neutral carbon tax would “work” in the United States. Just look at what happened in California to the “dedicated” uses of their cap-and-trade revenue.

Conclusion

The American public is being sold a bill of goods regarding a carbon tax. On the one hand, proponents tell progressive citizens about all the “green” goodies that can be funded with the trillions in revenue that such a tax will bring in. On the other hand, supporters assure conservative citizens not to worry, that the tax will be revenue neutral and will allow for huge cuts in the corporate income tax rate. As Dr. Evil would say, “Riiight.”