Summary

The Antiquities Act, signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, allows the president to designate federal lands as national monuments to protect archaeological and historical sites, often restricting resource extraction like drilling and mining to preserve these areas for educational purposes. In recent decades, this power has been abused by presidents, sidelining local stakeholders’ economic interests. The first monument, Devils Tower in Wyoming, was established in 1906 to safeguard a culturally significant natural wonder, reflecting the act’s aim to promote public good through preservation. Though intended to preserve national treasures, the Antiquities Act’s broad and improper application unnecessarily stifles domestic energy production and threatens the legislation’s own conservation goals.

_________

Download a PDF version of the brief

_________

Introduction

A 20th-century law intended to preserve national treasures on public lands has been abused by numerous presidents to prevent future drilling and mining, ignoring the interests of local stakeholders. Signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the Antiquities Act grants the president broad powers to declare federal lands as national monuments to preserve the land and regulate the removal of material. According to the National Park Service, “The Antiquities Act established that preservation of archeological and historical sites on public lands is in the federal government’s purview and in the public’s interest.” To preserve these sites, the act “obligated federal land-managing agencies to carry out measures to protect archeological and historical sites on their lands by implementing a permitting process and ensuring that any resulting collections went to educational institutions.” In short, the act prevents any resource or object extraction from land designated as a national monument that does not go to museums or other education-focused locations — although designations do typically respect existing leases for grazing and mining.

National monuments encompass a diverse array of areas deemed by the president to have cultural significance, ranging from the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument in Utah to the 0.34-acre Belmont–Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in Washington, DC. The vast difference in size between monuments highlights the different meanings attributed to the word, with the act defining them as “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, or other objects of historic or scientific interest.” Devils Tower, the eroded core of a volcano that has spiritual importance to multiple Native American tribes in northeastern Wyoming, was the first national monument established in September of 1906 along with its surrounding 1,513 acres. In his declaration of the monument, Roosevelt called the structure a “natural wonder” and “object of historic and great scientific interest,” adding that “it appears that the public good would be promoted by reserving this tower as a National monument.”

Prior to the act, Native American cultural sites, such as Cliff Palace in Colorado and Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, faced looting and desecration from both visitors and nature. Cliff Palace, for instance, deteriorated over time from a variety of natural effects including water, wind, and animals even before it was rediscovered in the late 19th century — which brought forth casual visitation and commercial exploration. The Mesa Verde Act of 1906, which was passed the same month as the Antiquities Act and “reaffirmed and strengthened sections” of the act, designated Cliff Palace as an archaeological national park and outlawed vandalism and looting. Although Cliff Palace was not established via the Antiquities Act and its designation had as much to do with soliciting tourism as preserving the site, it illustrates that the focus of Congress at the time of the act’s passage was on preserving public lands so that the structures they held could be used for public education.

Historic Uses of the Antiquities Act

Under the Antiquities Act, preservation was prioritized over all other potential uses of federal lands, marking a deviation from the federal government’s sole focus on selling these lands to states, individuals, and corporations under the General Land Office. Since it was assumed that recipients would primarily use the land for commercial purposes unrelated to preservation, maintaining federal control over lands correlated with protecting the objects and structures, both natural and man-made, inhabiting these lands. While the act does not explicitly restrict commercial uses of the land, it implicitly restricts any extraction that interferes with preservation for public education by declaring that in ruins, archaeological sites, and lands holding objects of antiquity, “examinations, excavations, and gatherings archaeological sites must be undertaken for the benefit of reputable museums, universities, colleges, or other recognized scientific or educational institutions.” Since monuments possess ruins and archaeological sites and hold antiquities by virtue of their designation as monuments, it follows that these sites are off-limits to commercial extraction.

This distinction poses little problem for monuments created as the law intended; section 2 of the act directs the president to restrict monument declarations “to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” New York City’s African Burial Ground is a 15,000-square-foot monument situated in the middle of Manhattan to memorialize the earliest and largest African burial ground rediscovered in the United States. Given its small size and proximity to surrounding buildings, the land provides no reasonable opportunity for any mining or drilling operations. Even for monuments not located in such densely populated areas, such as California’s 558-acre Muir Woods National Monument, it could be argued that there are benefits to preserving a sizable section of land to maintain the character of what it holds, in this case, 1,000-year-old redwood trees. Private interests could log these redwoods for profit, but the private gain of logging the trees within these acres would be minuscule compared to the public’s “historic or scientific interest” of preserving a select number of these trees, especially since 75% of redwood lands are held privately and logged. In the case of Muir Woods, the president stepped in to protect a small portion of historical and scientifically important federal lands while keeping the surrounding area open to commercial activity.

Uses of the Antiquities Act, however, have not followed this “smallest area compatible” standard and have instead allowed presidents to declare significant portions of federal lands off limits to commercial activity unilaterally. The first instance of this abuse occurred only two years after the act’s passage and by the president who signed it. In 1908, Roosevelt proclaimed 818,560 acres of Arizona Territory as the Grand Canyon National Monument and placed the Forest Service in control to prevent the construction of a trolley line. The Grand Canyon changed designations from a Forest Reserve in 1893, to a Game Reserve in 1906, and a National Monument in 1908 via presidential proclamations — it received its current National Park status in 1919 through an act of Congress. While all of these designations hindered access to the land — especially for the Havasupai Native American tribe, which used lands in the Grand Canyon for hunting and foraging in the winter — becoming a monument was more burdensome to usage than the prior declarations. Although its status as a forest reserve made the Grand Canyon distinct from other federal lands, the 1872 General Mining Law still applied, granting citizens and firms free access to explore for minerals. The monument designation changed this status. In the 1920 case Cameron v. United States, the Supreme Court affirmed that Ralph Cameron’s lode mining claim was invalid because he failed to demonstrate that his claim had an “adequate discovery of mineral” before the creation of the monument reserve. According to the court, “the inclusion of the major part of [the Grand Canyon] in the monument reserve withdrew that part from the operation of the mineral land law.” By designating the Grand Canyon as a national monument, Roosevelt made mining in any portion of its territory illegal unless one could demonstrate the validity of the mine before 1908.

Roosevelt set a precedent of declaring massive monuments that presidents have since followed. In 1943, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt drew criticism for creating the Jackson Hole National Monument in Wyoming to connect the state’s lowlands to Grand Teton National Park. This move angered local politicians and ranchers, who protested the move by driving their cattle across the monument. To force the withdrawal of the declaration, Wyoming sued the federal government in the 1945 case Wyoming v. Franke, alleging that the “area contains no objects of an [sic] historic or scientific interest required by the Act.” The U.S. District Court for Wyoming ruled against the state, declaring that the court “has a limited jurisdiction to investigate and determine whether or not the Proclamation is an arbitrary and capricious exercise of power under the Antiquities Act,” and that it would only step in “if a monument were to be created on a bare stretch of sage-brush prairie in regard to which there was no substantial evidence that it contained objects of historic or scientific interest.” Even though the court found against Wyoming and the Jackson Hole Monument was eventually absorbed into Grand Teton in 1950, the state was able to prevent future declarations of this kind from occurring when Congress passed an amendment to the Antiquities Act prohibiting the creation of any new or extension of existing monuments in Wyoming.

Other instances of executive overreach occurred under Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. In 1978, Carter designated 17 national monuments that protected over 50 million acres of land — a move that led Representative Don Young and Senator Ted Stevens to claim that the federal government was at “war” with Alaska — after Alaska Senator Mike Gravel threatened to filibuster legislation creating national parks, national forests, and wildlife refuges on these lands. While this land was not under immediate threat of “depredation and vandalism,” Carter viewed monument declarations as a method to protect against the risk of future “commercial exploitation.” As historian Hal K. Rothman explains, Carter used the Antiquities Act “as a means to rapidly reserve threatened land,” which “bought time for the National Park Service, the Department of the Interior, the president, and Congress.” In 1996, Clinton designated 1.7 million acres of southern Utah land as the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, claiming that the “lands covered by the monument represent a unique combination of archeological, paleontological, geologic and bioloic [sic] resources, in a relatively unspoiled natural state.” Like in Alaska, Utahns viewed this move as an abuse of power; as a 2010 New York Times article puts it, “the word ‘secret,’ especially when applied to the possible doings of far-away federal bureaucrats, is right up there with ‘monument’ in its ability to unleash vitriol among Western conservatives.” The “vitriol” among conservatives makes sense when considering the economic consequences of the monument, which a 2013 study estimated as a $146 million reduction in decade-to-decade growth in total nonfarm payrolls for nearby Kane and Garfield counties — primarily due to large coal and oil deposits.

As these 20th-century examples indicate, the Antiquities Act has been stretched beyond its limited mission of protecting historical sites from abuse to unilaterally closing off significant portions of federal territory to the chagrin of local politicians, communities, and corporations, who have no recourse besides going through Congress or a new administration.

The Antiquities Act Under the Obama, Trump, and Biden Administrations

Presidential abuses of the Antiquities Act continued into the 21st century under Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden. In contrast, President Donald Trump made the controversial decision to shrink two national monuments, raising questions about the extent of presidential power under the act.

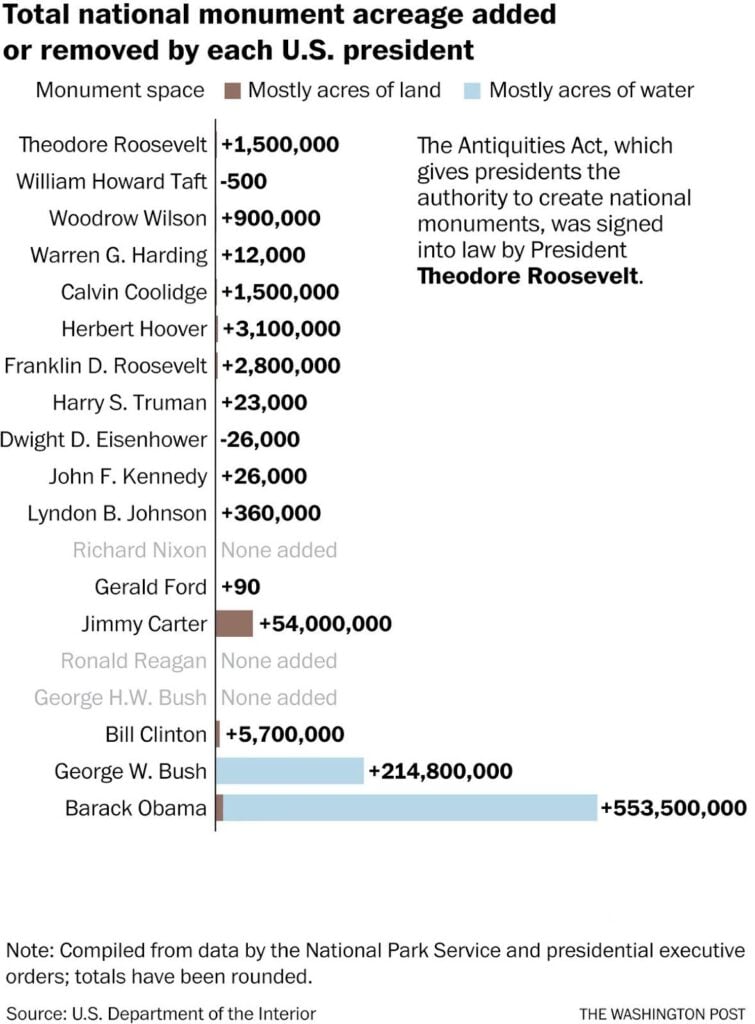

With over 29 national monuments — the most of any president — President Obama designated over 550 million acres of federal territory as national monuments, the vast majority of which are water. The largest marine monument created was the 582,578 square mile (372,849,920 acre) Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, which was originally established at about 140,000 square miles (89,600,000 acres) in 2006 under President George W. Bush. Located in the northern Pacific Ocean, northwest of Hawaii, the monument is the world’s largest marine protected area and hosts one of the world’s deepest and northernmost coral reefs. The monument also hosts the Midway Atoll, which is famous for the Battle of Midway in World War II. As a monument, commercial fishing is prohibited in Papahanaumokuakea, but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) can authorize subsistence fishing under a permit for Native Hawaiian practices. However, an attempt to allow the sale of fish caught in the monument area was opposed by NOAA and accused of being “a toehold for prohibited commercial fishing.” This aversion to the idea of selling fish caught in the monument area highlights NOAA’s focus on limiting any activity in the monument unless it aligns with the goal of maintaining the sanctuary as a “sacred site” for Native Hawaiians. However, the monument’s sacredness should be balanced with the economic benefits brought to Hawaii from commercial fishing. According to a study by Hing Ling Chan of NOAA and the University of Hawaii, the monument’s expansion “had negative impacts on the Hawaii longline fishery,” with an estimated 7% decrease in catch per unit effort and 9% decrease in revenue per trip. As Papahanaumokuakea shows, a monument’s ocean location does not mean that it does not have an impact on local stakeholders.

President Obama continued to use the Antiquities Act up to the end of his time in office, with one of his largest designations coming in December 2016. Located in southeastern Utah, the Bears Ears National Monument covers 1.35 million acres — an area larger than Delaware. In the declaration, Obama went for a quantity-over-quality approach when discussing the historical and scientific significance of the monument, listing elements ranging from the “cultural importance to Native American tribes” to the “star-filled nights and natural quiet” of the area. In response to the monument’s creation, a coalition of congressmen and senators from Utah protested the move in a jointly signed statement claiming that “the only difference with this monument designation is that government bureaucrats can now direct new land-management plans.” They continued: “[W]hen locals disagree with how the land is being managed, they are powerless to change it.”

Fortunately for Utah, President Trump moved to reduce the size of Bears Ears to roughly 228,000, which is about 15% of its original size, alongside cutting the Grand Staircase National Monument by about half from 1.9 million acres to one million during the first year of his presidency. Trump also moved to open the land formerly within both monument areas — Bears Ears in 2018 and Grand Staircase in 2020 — for mining and drilling. An economic analysis of Grand Staircase by the U.S. government estimated that coal production could lead to $208 million in annual revenue and $16.6 million in royalties alongside $4.1 million in annual revenues from oil and gas wells.

The move to reduce the size of these monuments was shrouded by legal uncertainty because the Antiquities Act does not “expressly authorize the President to modify or abolish national monuments established by earlier presidential proclamation.” University of Utah Law Professor John Ruple considered Trump’s action in a Harvard Law Review article and found that the Antiquities Act “does not expressly grant the President the power to revise or eliminate [monuments], and there is little to suggest that Congress intended to grant the President such powers.” Although presidents have reduced the size of monuments in the past, Ruple argues that Congress acquiesced in these cases because these reductions were to correct “errors and omissions resulting from incomplete or inaccurate boundary surveys” or to “improve protection of the resources identified in monument proclamations based on new information,” among other technical reasons that did not change the status of the monuments to the extent done by Trump. Other legal scholars defended Trump’s authority to reduce the monuments. Writing for the American Enterprise Institute, John Yoo and Todd Gaziano explain that a “presidential determination that the original designation was illegally or inappropriately large is a special case” and could “provide a sound predicate for declaring a designation to be invalid in some cases or for significantly reducing the monument’s size in others.” This finding would depend on the president determining that “some former monuments are illegally large relative to the original ‘object’ supposedly being protected.” In the case of Bears Ears, the Trump administration determined that it was “not confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of those objects.”

The legality of shrinking the monument designations remains a contentious issue since the litigation against Trump became moot once President Biden restored the boundaries of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase a year into taking office. Overall, Biden followed in Obama’s footsteps by designating a significant amount of territory — the most of any president at 674 million acres total, according to the New York Times — as monuments, including over 848,000 acres in California during his last week in office. One particularly noteworthy monument designation came in 2022 when Biden declared over 900,000 acres the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument in Arizona, permanently banning any uranium mining in the area. The administration attempted to diminish the effect of this ban by claiming that only 1.3% of the U.S.’ known uranium reserves were located in the monument’s territory. However, this assertion ignores the fact that the monument possesses a significant amount of the U.S.’s “high-grade uranium deposits,” which generally corresponds to a lower cost and environmental impact. Biden’s use of the Antiquities Act aligned with his overall strategy of restricting drilling and mining on federal lands through any means available, culminating in the closure of 625 million acres of U.S. coastal territory to offshore drilling through the 1953 Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. With the reelection of President Trump, Biden’s federal land closures are likely to be revoked. He rescinded the offshore drilling ban on his first day in office, and critics are concerned that he will again shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase alongside Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni and other monuments during his presidency.

Cumulative Acres Designated Over Time (1973–2023)

Policy Recommendations

As the historical evidence has demonstrated, presidents have used the Antiquities Act as a tool to enforce conservation by restricting the usage of federal lands, despite the desires of local stakeholders. Although not every monument declaration is deleterious to the interests of locals, ones that involve closing off a significant portion of land that previously had (or could have in the future) multiple uses signify that central planners believe they know how to use land better than states or individuals. In many instances, presidents cite historic or scientific motives for restricting the large portions of federal land that fail to stand up to cost-benefit analyses when acknowledging the potential for production from the land’s utilization.

Although the act requires presidents to cite the conservation of historic or scientific objects and structures as the reason for creating the monument, monument designations consistently have political undertones. Building one’s status as a conservationist can help build a president’s national political appeal — even while aggravating ranchers, miners, and local politicians by blocking them from the territory — and invite the support of local groups that advocate for protecting these lands, such as Native Americans.

The ease with which presidents can arbitrarily close off public lands for political gain is detrimental to the economic potential of local communities. Therefore, Congress must repeal the act and, if it finds that too difficult, look into reforms that control the president’s ability to designate monuments. This paper’s three core proposals are explained in the following section:

1) Repeal the Antiquities Act

Even if Congress reforms the Antiquities Act by reducing the acreage the president can declare as a monument, the issue of unilateral executive decisions being made on lands utilized by local stakeholders still persists. The only way to eliminate this problem entirely is to repeal the act, preserving the monument-making power with Congress exclusively. Repealing the act makes sense when examining the context in which it was created — which was to expeditiously protect archaeological sites and natural wonders from being desecrated, many of them in New Mexico and Arizona. Notably, New Mexico and Arizona did not become states until 1912, indicating that it was more difficult for local interests to advocate for the protection of these sites at the time. This authority is no longer needed to protect these sites; as Nicholas Loris explained for the Heritage Foundation, “The purpose was to give the federal government an expeditious path to protect archeological sites…Such a quick, unilateral means to designate land is no longer necessary.” If such a need for quickly protecting federal lands does emerge, it should be obvious enough to Congress that they feel the need to declare it as a monument without extensive politicking. History has shown that Congress is more than capable of protecting federal territory without the president stepping in. According to Jonathan Wood, vice president of law and policy at the Property and Environment Research Center, “when the president’s power is reduced, Congress takes a greater interest in the management of federal lands.” Wood also adds that any concern about damage to artifacts is covered by the 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act, making the Antiquities Act redundant in this respect. Additionally, the great degree of regulations affecting drilling, mining, or development on federal lands means that significant time and paperwork need to be completed before these acts are permitted, giving Congress plenty of time to act.

2) Require congressional approval for monument designations larger than 320 acres.

Before Congress passed the Antiquities Act, a much narrower bill was proposed in 1900 by Representative John Shafroth of Colorado that allowed the secretary of interior to reserve any public lands containing “monuments, cliff dwellings, cemeteries, graves, mounds, forts, or any other work of prehistoric, primitive, or aboriginal man,” with a limit of 320 acres. The original bill limited territory creation to Colorado, Wyoming, Arizona, and New Mexico — the latter two of which were territories at the time — but this limitation does not need to apply to a contemporary version of this bill. Legislation of this kind would significantly reduce the president’s ability to declare vast tracts of federal territory as monuments. By limiting the size of monuments, presidents would be forced to choose the most historically or scientifically important portions of federal territory when declaring monuments, allowing for other uses for the rest of the territory. This limitation would reduce the level of tension between the president and locals created by monument designations. Moreover, listing out the type of objects/lands permissible for preservation would reunite the act with its original purpose of reserving small, vulnerable portions of land, preventing the act’s abuse by presidents who insist that almost anything old or natural can be considered historic or scientific. Although this language does not include forests, coral reefs, or any other element of nature, additional categories could be added to accommodate these elements, or it could be left to Congress to conserve. To prevent the president from creating many smaller monuments to make up for the size restriction, a clause restricting the president from creating contiguous monuments would have to be included. It may be desirable to have monuments larger than 320 acres in some instances, but to do so would require Congress to agree.

3) Make the president’s power to reduce existing monuments explicit.

Because the legal debate over whether the Antiquities Act grants the president the authority to reduce the size of monuments remains unsettled, Congress should take the lead and explicitly grant the president this authority. Releasing all of the land that previous presidents have tied up as monuments can be streamlined through executive action, avoiding the gridlock incumbent with congressional debate. Members of Congress, even those who are generally opposed to monument designations, would likely stall bills that shrink or eliminate monuments based on a monument’s location — if it is located near their district, for instance — making a comprehensive monument-reducing bill infeasible. Thus, it makes more sense to grant the president the ability to make decisions regarding how/where to shrink monuments as it would allow the decisions to be made more efficiently. While this bill would grant the president additional authority, it is authority only to reduce, not extend, the size and degree of restrictions on federal lands.

Conclusion

In its current form, the Antiquities Act is little more than a weapon utilized by presidents to score political points by building conservationist reputations while neglecting the needs and desires of local interests for federal lands. Although the idea of protecting archaeological sites on federal lands does hold some merit, the Antiquities Act’s language is sufficiently vague to permit presidents to expand their authority well beyond that, stretching the definition of what it means for something to be of “historic or scientific interest.” By ignoring the “smallest area compatible standard” set by the act, presidents can score quick political points by designating millions of acres of land as monuments, thereby restricting any drilling or mining on that land. Production on these lands does not often have drastic implications for national economic growth, but it does harm local stakeholders that have planned to utilize these lands. Moreover, the long-term economic benefits of restricting access to these lands are difficult to realize because prospectors are discouraged from exploring them for their development potential.

With the inauguration of President Trump and Republican control of both houses of Congress, the time is ripe for Congress to consider either repealing or reforming the Antiquities Act. In his first term, President Trump took steps to shrink the size of monuments and, since Interior Secretary Doug Burghum has recommended that Trump overturn “burdensome regulations” created under Biden, he will likely do the same this time. Congress should provide Trump with the statutory support required to ensure that legal challenges will not stifle his efforts to reduce monuments. For the long term, however, Congress must devote time to re-evaluating the Antiquities Act with consideration of its detrimental impact on commercial land use.

_________

Prepared by William Rampe, Communications Associate | wrampe@ierdc.org

_________