Avid golfers know that when you hit a really awful tee shot, you get to take a Mulligan—a do-over. In the debate over government climate change policy, a typical argument is to claim that there are no Mulligans. For example, the New York Times recently ran a critique of climate scientist John Christy, saying that “if he is wrong, there is no redo.” Naturally, this is supposed to make the reader embrace an interventionist government crackdown on carbon dioxide emissions.

Yet this argument is seriously flawed. First, we can flip it and use it against those arguing for government intervention: There’s no redo on their bad consequences, either. Second, these critics (as usual) simply ignore the published literature: Even the latest IPCC report says governments can wait till 2030 before doing anything, and the result will merely be an increase in the cost of the policies.

The Other Side Can’t Get a Mulligan, Either

As we’ve said, it’s easy enough to take the rhetorical move and deploy it against those clamoring for aggressive government action. For example, Joe Romm assures us that even very strict limits placed on carbon dioxide emissions will be “super cheap.” What if he’s wrong? What if his favored policies drive up electricity prices and cause serious hardship and job losses (as the carbon tax did in Australia)? Is Romm going to personally reimburse these people after admitting his mistake?

The alarmists like Romm would probably retort that the risks of inaction include widespread deaths, while the downside to aggressive government intervention are merely higher energy prices. Yet this is wrong. Especially in underdeveloped regions like Africa, the rapid proliferation of efficient energy production is a way to literally save lives (and greatly enhance living standards). A Forbes article last month reported:

Since 1990, 650 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty, infant mortality has been reduced by 70%, and life expectancy has increased six years – a historic evolution powered by coal, and what the IEA has referred to as an “example” for other developing nations. Africa needs more electricity, more coal, more gas, more nuclear, more renewables. The Sub-Saharan region, with a population of 910 million people, uses less electricity per year (145 TWh) than the state of Alabama (155 TWh) with just 4.8 million. There is only enough electricity generated in Sub-Sahara to power one light bulb per person for three hours a day. Over 65% of the population lives without any electricity at all.

Like it or not, the quickest way to provide electricity to billions of the world’s poorest people is to construct many more coal-fired power plants. Perhaps in the year 2075 coal will no longer be advantageous, but right now it has a lot going for it—that’s why the market naturally gravitates toward coal-fired plants, and why the government has to go out of its way to penalize coal.

If people like Joe Romm get their way, over the coming decades there will be dead bodies to show for it. So let’s not kid ourselves that the tradeoff is between death from climate change versus annoying prices at the gas pump—people can die on either side of the spectrum, depending on who is right and who is wrong. To try to knock out John Christy’s views because they are “risky” is a complete non sequitur; the dangers to economic growth from government policies are very serious as well.

Even IPCC Rejects the Alarmist Argument

Yet there’s another reason that the objection against John Christy is silly: It is simply not true that we only get “one shot” at climate change policy. Even the latest IPCC report indicates that humanity can afford to take another 16 years to further study the situation.

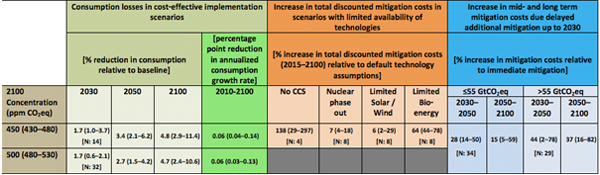

I’ve shown the following table in previous posts, but it’s worth doing here again. It’s taken from page 16 of the Working Group III Summary for Policymakers from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that came out earlier this year:

I walk through it carefully in my earlier blog post but let me give the main point here again: The blue columns on the far right show the percentage increases in the total (undiscounted) mitigation costs necessary to achieve the far-left (brown cells) atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases in the year 2100, for the years 2030-2050 and also for 2050-2100, for two different scenarios of total emissions (either below 55 gigatons of CO2-equivalent, or above).

In other words, these blue cells show us how much a delay of government action through the year 2030 will increase the cost necessary to achieve the specified (and very aggressive) atmospheric concentrations for the year 2100, shown on the far left of the table in the brown cells. Specifically, the blue cells show that by “doing nothing” about climate change until the year 2030, even in a high-emission baseline scenario, the IPCC’s best guess of the cost of achieving the aggressive outcome rises by 44% in the years 2030-2050 and 37% in the years 2050-2100. Furthermore, in the low-emission scenario, for the latter half of the 21st century the cost only rises a mere 15 percent, as one of the blue cells indicates.

Finally, I should point out that the cost increase drops dramatically if we weaken the atmospheric target. I didn’t include it in the table above (because it was already too cluttered), but the actual IPCC report shows that for a more modest target of limiting atmospheric greenhouse gases to 550 ppm by the year 2100, the cost penalty from delaying action until 2030 is 15-16 percent in the high-emission scenario and a piddling 3-4 percent in the low-emission scenario.

So what does all this mean? Depending on the particular climate targets we have in mind, and our assumptions about the baseline growth in emissions, even the IPCC’s latest report says that governments “doing nothing” about the climate until the year 2030 will probably increase the cost of the policy somewhere in the range of about 3% to 40%. And since guys like Joe Romm have been telling us that if we “act now” it will be “super cheap,” a cost increase of 3% to 40% is certainly do-able.

Conclusion

Like other alarmists when it comes to the climate debate, the recent NYT critics of John Christy use a cheap rhetorical device—warning readers we won’t get a “redo” if he’s wrong—that makes no sense. To the extent that it’s valid, we can just as well deploy it against those wanting bigger government, since people who die from lack of electricity only get “one shot” as well.

Furthermore, these critics simply ignore what even the IPCC says in its latest report: There is no urgent need to “act now!” Humanity can afford to wait and collect more evidence to make sure we understand the situation. Delay won’t spell catastrophe; even the IPCC says it will merely increase the price of the desired policy, and that price hike could be very modest depending on the exact scenario.