Currently, there are about 5,000 miles of carbon dioxide pipelines in the United States, used mostly to inject it underground to move oil to the surface through enhanced oil recovery. The 2021 infrastructure law, which included billions in funding for carbon capture demonstration and pilot projects, could change that number dramatically. Companies are proposing thousands of miles of pipelines to deliver carbon dioxide captured from ethanol plants and other facilities to permanent underground storage sites. In fact, the CO2 pipeline network could expand more than twelvefold if midcentury climate targets are reached. According to some analysts, as many as 65,000 miles of carbon pipelines will be needed for the country to reach net-zero emissions by 2050—a goal of President Biden. The 2021 infrastructure law provides a federal carbon capture tax credit of $50 per ton.

According to some safety advocates, there are loopholes in federal safety regulations that could leave carbon dioxide pipelines largely unregulated. Pipelines being converted from shipping natural gas to carrying carbon dioxide are not covered by the current rules. Existing standards to move carbon dioxide for enhanced oil recovery also may not be adequate for new pipeline projects. According to pipeline companies, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) in the Department of Transportation has jurisdiction over the carbon dioxide pipelines planned in the Midwest. But, opponents want a moratorium on construction of the projects until new federal regulations for carbon dioxide pipelines are completed. PHMSA has begun an overhaul of its existing rules, with a first draft expected around October 2024. PHMSA regulations often take years to implement, delaying action further.

Proposals for CO2 Pipelines

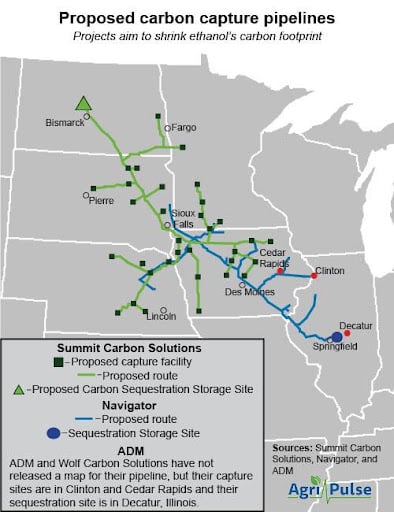

Navigator CO2 Ventures is seeking approval from regulators in several states to build the Heartland Greenway, a 1,300-mile pipeline network that would take CO2 captured from biofuel makers across the Midwest to a sequestration site in central Illinois. In January, the Illinois Commerce Commission, which is weighing approval of Navigator’s project, sent a request asking PHMSA whether the federal agency would regulate the pipeline once built and to what extent PHMSA inspects such pipelines. Navigator’s over $2 billion project would stretch across Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, Minnesota and Illinois and would sequester up to 15 million tons of CO2 annually worth $750 million in tax credits from ethanol and fertilizer plants.

Members of the Iowa Utilities Board last month indicated its agency is preempted by federal law and regulation from getting involved in safety matters, which are “clearly under the jurisdiction of PHMSA.” The board was ruling on whether it would require Summit Carbon Solutions LLC , the developer of another pipeline, the Midwest Carbon Express, to file safety assessments of its project. The $4.5 billion project is planned to include about 2,000 miles of pipeline in Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota, with the sequestration site where liquid CO2 will be injected underground in North Dakota. Summit has signed up 31 ethanol plants as partners in the project, designed to capture more than 10 million tons of carbon dioxide annually worth $500 million in tax credits.

A third project, the ADM/Wolf project will transport CO2 from ADM’s ethanol and cogeneration facilities in Clinton and Cedar Rapids to be stored permanently underground at ADM’s fully permitted and already-operational sequestration site in Decatur, Illinois. The 350-mile pipeline “would have significant spare capacity to serve other third-party customers looking to decarbonize across the Midwest and Ohio River Valley,” according to the companies. The pipeline would be able to transport 12 million tons of CO2 worth $600 million per year in tax credits.

Summit, Navigator and Wolf Carbon Solutions objected to being required to submit safety assessments since the federal government has authority over safety. The companies have filed at least four federal lawsuits against local governments in Iowa and South Dakota challenging zoning and permitting regulations adopted in response to the projects.

CO2 Characteristics

The jurisdictional issue partly stems from the unique characteristics of how carbon dioxide behaves when transported. PHMSA’s existing regulations cover pipelines carrying carbon dioxide in a “supercritical” phase–a liquid-like phase that requires high pressures and certain temperatures. According to the developers of the Midwest pipelines, the carbon dioxide in their lines will be in that state at certain points of its journey, such as the beginning and end. In between, temperatures and pressures will change. For it to stay in the supercritical state, the CO2 would need to remain above 88 degrees Fahrenheit, which would not be the case throughout the pipeline’s traverse.

In addition, many of the new pipelines will be in more densely populated areas than the western Plains where many of the current EOR pipelines are located. The projects also face resistance from landowners and environmentalists who question the value of carbon capture and sequestration in fighting climate change, and object to the prospect that some of the companies might seek to condemn land under eminent domain.

Not All CO2 Pipelines are Supercritical

Another prospective pipeline would not operate at all under the pressures needed for supercritical CO2. Tallgrass Energy LP is proposing to convert its Trailblazer natural gas transmission pipeline in Nebraska and Wyoming to carry carbon dioxide for storage at a site near Cheyenne, Wyoming. As a natural gas transmission pipeline being converted to carry CO2, PHMSA’s regulations currently would not cover it. According to Trailblazer, the “vast majority” of the pipeline’s permits still apply, including state permits for air quality and environmental protection. The converted Trailblazer pipeline is projected to be operational around the time that the draft PHMSA regulations would be released.

Conclusion

The Biden administration is promoting carbon capture projects as an important part of its plans for cutting greenhouse gas emissions and the 2021 infrastructure bill he signed provides lucrative tax subsidies to develop the industry. To reach Biden’s climate goals, the proposed CO2 pipelines will be necessary to maintain a vibrant ethanol industry. The issue is who is going to regulate them and provide for the safety of the American public. DOT’s PHMSA currently regulates supercritical CO2, but the CO2 pipelines do not keep CO2 at supercritical temperatures for the entire route and natural gas pipelines converting to CO2 also do not. That raises an issue of, if not PHMSA, then who?