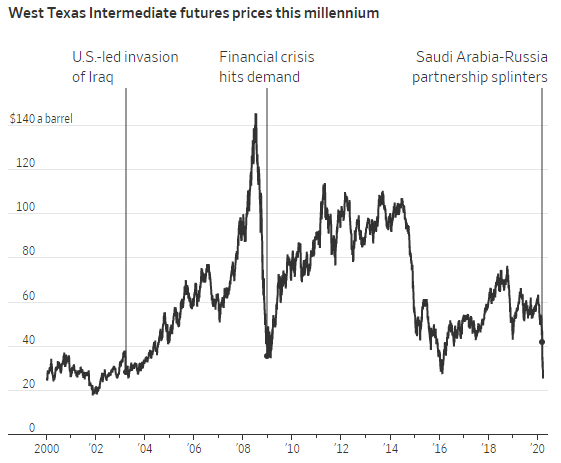

In early March, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other big OPEC countries gathered in Vienna to plan production cuts that could put a floor under falling prices due to the outbreak of coronavirus. At that time, crude oil was trading at over $50 a barrel. At the meeting, Moscow would not agree to Saudi Arabia’s proposed cuts, ending a three-year-old pact that the countries had maintained to manage global oil supplies. In retaliation, Saudi Arabia slashed oil prices and announced plans to increase oil output, driving down the price of oil that was already plunging due to the coronavirus outbreak. Oil now trades well below $30 a barrel. As of Monday, March 23, WTI crude was at $22.48 and Brent crude was at $25.83. Both Russia and Saudi Arabia are dependent on oil sales to fund their national budgets. But, because Russia has saved money since the last oil-price crash in 2014/2015, giving it a financial cushion and because the biggest losers in an oil-price war will be high-cost U.S. shale producers, Russia felt it could weather the storm and inflict economic harm on the United States.

Russia

Russia has spent the last five years tightening its budget and building a $550 billion reserve that should allow it to handle oil prices between $25 and $30 a barrel for up to a decade. Recently, Russia’s finance ministry said that it would draw from its $150 billion national fund in order to supplement the budget if oil prices stay low. If crude oil sells for an average of $27 a barrel, for example, Russia would need to draw $20 billion a year from the fund to balance the budget.

Russia decided to restructure its economy after the recession in 2015 that followed Western sanctions over the annexation of Crimea and OPEC’s decision to increase oil production in 2014. Despite Russia being in a better position now to handle the current low oil prices than it was in 2014/2015, Russian President Vladimir Putin is challenged by his need to fund infrastructure investment and social programs in order to obtain the popularity he had in the early 2000s when oil prices were high. Economic growth is a focal point of Putin’s current presidential term as he promises to help turn around long-stagnant living standards. Lowered incomes and austerity have been the source of his falling popularity and a key factor behind a January government reshuffle that forced Dmitry Medvedev to resign as prime minister.

In Russia’s view, efforts to keep oil prices high by limiting output was what boosted shale oil production in the United States. Reducing the U.S.’s market share is the country’s main objective by pulling out of the Saudi deal. With U.S. shale oil producers facing higher production costs and debt incurred in their rapid expansion, Russia believes cheap oil will push many U.S. firms into bankruptcy or restructuring. The added benefit of reducing U.S. oil output may also limit America’s ability to levy meaningful sanctions.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia also has cash reserves to withstand lower prices, but theirs are less than Russia’s. Saudi Arabia is looking at a fiscal deficit of about $50 billion, and lower oil revenues will raise that by another $70 billion to a $120 billion. At that rate, the Saudi reserves could last for about four years at best. Saudi Arabia needs oil to be roughly twice as expensive as Russia does in order to balance its budget. It is lowering oil prices to force Russia to rejoin the informal OPEC+ grouping.

Like Russia, Saudi Arabia has an ambitious plan—Saudi Vision 2030—to spend billions to turn the Saudi economy from an oil state into a modern economy, which requires revenues from oil sales.

Despite collapsing oil prices and raising exports from 7-plus million barrels a day to 9-plus million barrels a day or more, Saudi Arabia may be able to make the same amount of money as it would have in a world without Russian cooperation by obtaining a larger market share.

U.S. Shale Oil Producers

The U.S. shale oil industry proved resilient in the past when OPEC flooded the market with cheap oil in 2014 and 2015. When prices fall, U.S. production falls, just enough to get prices up, and then rigs start pumping again—a self-regulating mechanism. While the U.S. oil industry may have less cushion now than it did before, some analysts believe it may still be able to absorb the price fall. The United States has leaner and more efficient operators in America’s shale plays, especially the Permian Basin in Texas and the Marcellus in Pennsylvania. The United States is producing record levels of oil and natural gas with 50 percent fewer rigs than a decade ago.

The difference this time is that the coronavirus is also pushing demand down. U.S. oil producers are expected to slash output and investment, while containment measures implemented to slow the coronavirus’s spread stop consumers from spending much of the money they save from lower-priced gasoline at the pump. With flights grounded and borders closing, demand for oil and its refined products has plummeted.

Conclusion

It is unclear how long the Saudi-Russian oil price war will last. While both countries have cash reserves, their objectives of improving the living conditions of their populations mean they need more revenues to finance them, which they obtain from the sale of oil. While both countries would like to destroy the U.S. shale oil industry, past experience has shown the U.S. oil industry to be highly resilient and able to come back with a vengeance after a price fall. The industry has improved technology and productivity to lower their costs and may be able to do so again.