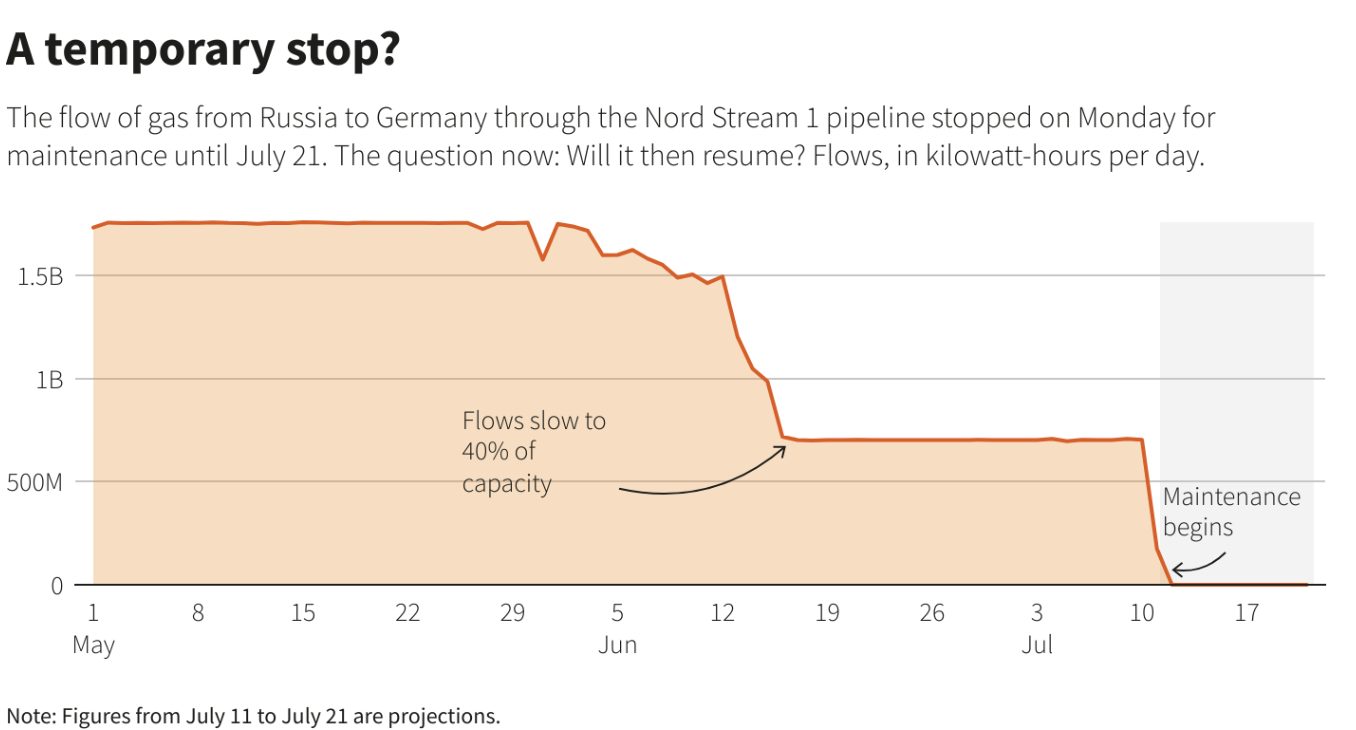

Between July 11 and July 21, Russia will shut the Nord Stream 1 natural gas pipeline for maintenance, as they have done in the past. However, there are new worries in Europe that Russia will not restart the pipeline after the 10-day period. The Nord Stream 1 pipeline transports 55 billion cubic meters a year of natural gas from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea. Last month, Russia cut flows to 40 percent of the pipeline’s total capacity because of a delayed return of equipment being serviced by Germany’s Siemens Energy in Canada. Apparently, Canada has decided to return the sanctioned equipment and the Biden administration supports Canada’s actions. If Russia extends the scheduled maintenance to restrict European gas supply further, Europe will have difficulty in filling gas storage for winter, heightening its energy crisis that has escalated bills for consumers.

Russia has cut off natural gas supplies to several European countries that did not comply with its demand for payment in rubles. While there are other large pipelines from Russia to Europe, flows have been declining gradually and Ukraine halted one gas transit route in May because of interference from Russian forces.

Germany is very dependent on Russian natural gas and has moved to stage two of a three-tier emergency gas plan—just one step before the government rations fuel consumption. Germany’s economy ministry wants Germans to begin servicing their furnaces, installing water-saving shower heads and preparing to lower their heating by at least one degree in the winter to save energy. Germany may need to cut its consumption of natural gas by 29 percent to prevent storage from running dry if Russian gas was permanently cut off. The country’s Parliament will lower the temperature in its offices by two degrees when the heating period begins. Many heated public swimming pools have also reduced their temperatures.

The German government has also warned of a recession if Russian gas flows are halted. The impact to the German economy could be 193 billion euros ($195 billion) in the second half of this year. An abrupt end of Russian gas imports would also have a significant impact on the workforce in Germany with about 5.6 million jobs affected. The impacts would go beyond Germany to the rest of north-western Europe with escalating energy prices. Wholesale Dutch gas prices, the European benchmark, have risen more than 400 percent since last July and an extended shutdown could have an even greater impact.

Europe’s Alternatives

Russia supplies about 40 percent of Europe’s natural gas, mostly by pipeline with deliveries last year totaling around 155 billion cubic meters. The Ukraine transit corridor sends gas to Austria, Italy, Slovakia, and other east European states. Ukraine cut off some of these supplies, closing the Sokhranovka transit pipeline that runs through Russian-occupied territory in the east of the country. Alternative routes to Europe that do not go through Ukraine include the Yamal-Europe pipeline, which crosses Belarus and Poland to Germany, and Nord Stream 1, which runs under the Baltic Sea to Germany and is currently shut down for maintenance. Austria, Germany, Italy, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic receive gas via Nord Stream 1.

The Yamal-Europe pipeline has a 33 billion cubic meter capacity, carrying around a sixth of Russian gas exports to Europe. Natural gas has been flowing eastward through the pipeline from Germany to Poland since the start of this year. Russia, however, placed sanctions on the owner of the Polish part of the Yamal-Europe pipeline that carries Russian gas to Europe. Poland can manage without reverse gas flow on the Yamal pipeline in part because it has reversed plans to reduce coal use in the face of Russian aggression in Europe.

Some countries have alternative supply options and Europe’s gas network is linked so supplies can be shared. Germany, Europe’s biggest consumer of Russian gas that has halted certification of the new Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine, could import any available gas from Britain, Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands via pipelines. Norway, Europe’s second biggest exporter behind Russia, has pushed up production to help the European Union towards its target of ending reliance on Russian fossil fuels by 2027. The Groningen natural gas field in the Netherlands could help neighboring countries in the event of a complete cut-off in Russian supplies.

Britain’s Centrica signed a deal with Norway’s Equinor for extra natural gas supplies to the United Kingdom for the next three winters. Britain does not rely on Russian gas and can also export to Europe via pipelines. Southern Europe can receive Azeri gas via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline to Italy and the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline through Turkey.

Biden has committed the United States to supplying 15 billion cubic meters of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the European Union this year. However, U.S. LNG plants are producing at full capacity and an explosion last month at a major LNG export terminal in Texas has idled it until September and it will operate only partially from then until the end of 2022. Europe’s LNG terminals currently have limited capacity for extra imports. However, some European countries are seeking ways to expand imports and storage. Germany is to build two LNG import terminals in the next two years.

Poland, which meets about 50 percent of its gas consumption with Russian gas (around 10 billion cubic meters), can source gas via two links with Germany. In October, a pipeline with up to 10 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year will be opened between Poland and Norway.

Instead of obtaining natural gas to directly generate electricity, some nations could fill gaps in electricity by importing via interconnectors from their neighbors or by increasing power generation from nuclear, renewables, hydropower, or coal. Nuclear capacity, however, is being retired in Belgium, Britain, France, and Germany and some reactors are facing outages. The German government recently voted to close its last three remaining nuclear reactors by the end of the year. Nuclear power accounts for 6 percent of Germany’s electricity and could help to divert gas for electricity generation to industry that is highly dependent on natural gas as a fuel and feedstock. Germany, however, is betting on wind and solar power despite recent low winds and lack of transmission lines to carry the power from places with good wind and sun to areas with factories and homes that need power.

Since gas is less available, renewables are less reliable, and nuclear remains undesirable, which leaves coal. Since mid-2021, Europe has had to switch some of its retiring coal plants back online despite trying to shutter them to meet their Paris Climate Accord targets. Germany passed a law to bail out utility companies and bring coal-fired power plants back online.

Conclusion

The situation in Europe and particularly Germany, which is 30 percent dependent on Russian natural gas, is dire. Should Russia not open the Nord Stream 1 pipeline after its annual maintenance, it is unlikely that the natural gas storage facilities in Europe will be filled up sufficiently to make it through the winter months. Germany has already instituted stage 2, which is just before rationing, of its plan to conserve natural gas. However, as dire as its situation is, Germany has approved shuttering its last three nuclear reactors by the end of the year. It is placing its bets on wind and solar power despite low wind resources and a lack of transmission lines to move power from good wind and solar areas to demand centers. Many are watching Europe’s experience with renewable energy closely, since it mirrors the plans President Biden continues to push for the United States.