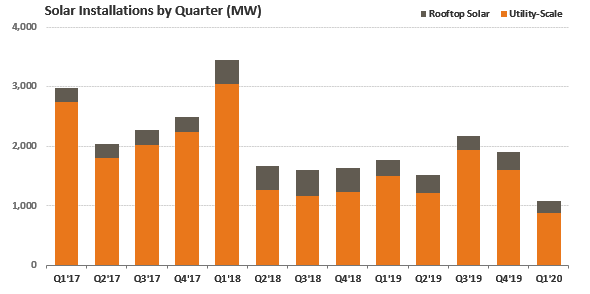

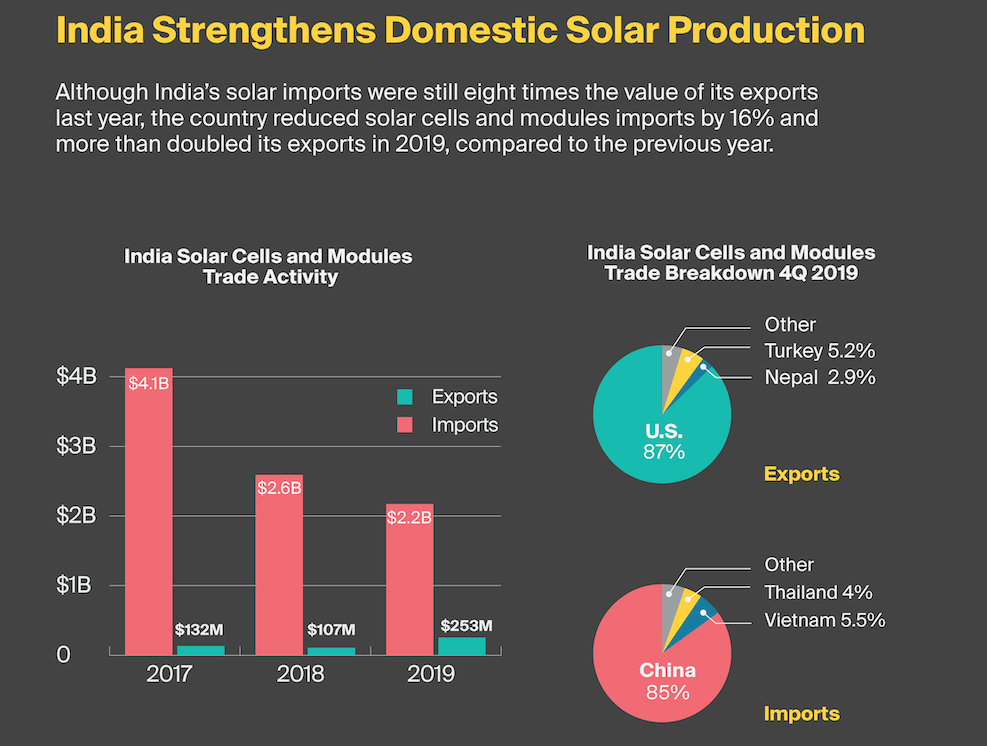

India has a goal of installing 100 gigawatts of solar power by 2022 , or slightly less than 10 percent of the generating capacity of the entire U.S. grid. India currently has 36.8 gigawatts of installed solar capacity with another 36.9 gigawatts in the pipeline. However, it is expected that solar installations will total only about 5 gigawatts this year mainly because of delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Currently, India imports about 85 percent of its solar modules and cells from China. An additional 5.5 percent are imported from Vietnam and 4 percent from Thailand, but those companies are mostly controlled by China. Disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic resulted in India’s first-quarter 2020 solar installations (1,080 megawatts) to be the lowest since 2016, dropping 39 percent from a year earlier (1,761 megawatts).

As a result, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a national strategy called “Atmanirbhar Bharat,” or “Self-Reliant India” to scale up India’s manufacturing capacity. The late start will allow India’s manufacturers to adopt the latest technology to make high-end products, such as high-efficiency solar cells.

In June, India announced that it would impose duties of up to 25 percent on solar modules and a 15 percent tariff on solar cells from China and Chinese-controlled companies. The duties are a continuation of taxes that were levied starting in 2018 to protect domestic manufacturers of solar parts. There are plans to increase these taxes after one year.

China Dominates the Solar Market

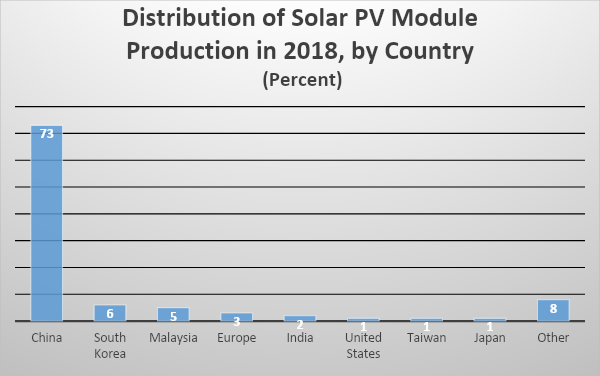

When Chinese companies first began making solar panels, they bought manufacturing equipment from Germany and Japan, gradually replacing it with domestic equipment that performed the same function. They now have supplanted international rivals and command a dominant position in the global market due to massive amounts of investment that have increased production and driven down costs. Eight out of the world’s top 10 solar panel makers are Chinese. China is by far the world’s biggest producer with a 73 percent market share. Second-ranked South Korea has 6 percent of the market.

Longi Solar, the world’s sixth-largest solar panel maker, is based in Taizhou, about 200 kilometers northwest of Shanghai. Because Longi specialized in making the high-performance monocrystalline silicon used in industrial-grade panels for solar power plants, it could channel its revenue from its silicon materials business into solar panel factories, allowing it to become the number 6 panel maker globally in only four years. The company’s 146,000-square-meter (1.57 million square foot) plant began operating in 2016. The plant can turn out 4 million kilowatts worth of panels a year–about 70 percent of Japan’s annual demand. Most of the work at the plant is done by machine, allowing most of the factory’s 600 workers to be engaged in quality control and inspection of the finished products. Longi plans to increase its production capacity about fourfold to 30 million kilowatts by the end of 2021.

In 2011, China introduced a feed-in tariff for renewable energy, which helped to develop its solar panel market. The country accounts for about half of global solar panel demand. China and Japan, however, have largely ended the subsidized rates at which solar energy was sold to utilities, while many industrialized countries continue to provide subsidies for solar power, including the United States and many U.S. state governments. The United States and India have imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels, which has helped to stop the flood of imports from China.

Recent Developments Increased Chinese Module Prices

Prices of China’s solar modules have increased for the first time since 2017 because of the closure of two Chinese manufacturing plants due to an explosion at one and flooding at another. The cost of a single multi-crystalline solar module increased to over $17 Rupee ($0.23 U.S.) from $16-16.5 and the price of a mono-crystalline module increased to between $18 and $19 Rupee from about $17.5. The equivalent tariff impact on new projects is estimated at about 0.07 Rupee per kilowatt hour ($0.001 U.S.). The increase in prices came as a surprise since solar module prices had been consistently decreasing. As with everything else, they were bound to eventually increase, but the Indians found themselves at the whim of Chinese manufacturers on whom they now depend for 85 percent of their solar equipment.

As a result, Chinese module suppliers are reneging on signed contracts unless higher prices are paid.

Conclusion

The solar module supply chain is controlled almost entirely by China, who has 73 percent of the world market, and Indian solar developers are left with no option but to buy from them. The solar industry in India is procuring modules from the Chinese because presently there is no other option. But, India’s prime minister Modi wants to change that and develop a solar manufacturing industry domestically. He has imposed duties on solar modules and cells from China, which may slow the country’s transition to solar energy. Duties are part of a wide range of Indian government actions aimed at building domestic manufacturing and becoming less energy-dependent upon China.