The coronavirus pandemic has forced some airlines into bankruptcy and others may be nearing bankruptcy. Business and leisure travel both have dropped significantly, and pilots are flying nearly empty planes around the United States and Europe. Before the coronavirus took its toll on international air travel, 37,826 aircraft were flying on November 5, but by March 31, just 26,217 planes were active—a decrease of 31 percent. The International Air Transport Association (IATA), a trade group of nearly 300 airlines worldwide, indicated that airline revenue would decline by $252 billion in 2020 with recovery not likely until 2021. The trade association estimates that 1.1 million flights will be cancelled through June 30. Many airlines are operating flights that are only 20 or 30 percent full, despite significant cuts in service and despite the low level of passengers. And, flight crews are worried about catching the virus and bringing it home to their families.

The decrease in flights has resulted in less consumption of jet fuel, resulting in decreasing margins at refineries, and requiring other uses and/or storage for existing volumes of the fuel.

Airlines are retiring older planes and finding places to park them. Qantas and KLM will retire their 747 planes—a model that KLM had operated for 49 years and planned to retire in 2021. In Copenhagen, airport authorities are closing taxiways to house some of the Scandinavian Airlines fleet. Lufthansa is using a new airport in Berlin that has not yet opened and a runway in Frankfurt to park its planes.

U.S. Airline Industry

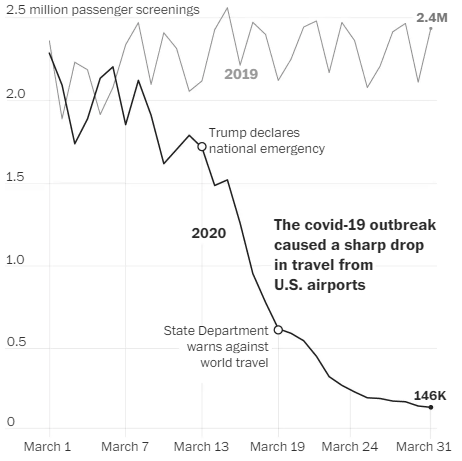

The U.S. airline industry employs 750,000. Before the coronavirus outbreak, U.S. carriers were transporting about 2.5 million passengers daily. In January, 61.2 million passengers flew domestically, and 9.1 million flew internationally. But, on March 31, the TSA screened just over 146,000 passengers at U.S. airports—a 94 percent drop from 2.4 million on the same day last year. That downturn is depicted in the chart below. By the end of March, the TSA screened just over 35 million passengers at U.S. airports during the month—a 50 percent decrease from more than 70 million at the end of March last year. A week later the situation got worse. The number of people flying in the United States dropped to below 100,000 on April 7—95 percent below the level a year ago.

Source:

The outlook for this summer is not much better. Newly revised federal rules will let the airline companies decrease some routes by as much as 90 percent through September and eliminate others altogether to avoid flying nearly empty planes. A carrier that served a city less than five times weekly would need to provide just one flight a week under the new Department of Transportation rules on minimum domestic flying levels through September 30. A company with more than 25 weekly flights would be able to scale back to just five. On some routes, the decrease in service could be around 90 percent.

U.S. airlines are also retiring their older planes, and flying their newer, more efficient planes during the downturn. The first planes to be retired are the wide-body jumbo jets, relatively old and inefficient models, such as the Boeing 747 and the Airbus A340. American Airlines is accelerating the retirement of its Boeing 767 and 757s. It is putting planes in the parking lot at its maintenance facility in Tulsa and is flying its fleets to storage in Mobile and Birmingham, Alabama, and Roswell, New Mexico.

Delta Air Lines is retiring its McDonnell Douglas MD-88s and MD-90s. Because of the need to downsize due to the lower demand in flights, Delta is also parking its efficient, smaller jets, including its Boeing 717 fleet, and newer long-haul planes, such as the Airbus A350.

Airlines have also offered early retirement to their pilots. Over 600 American Airlines pilots close to retirement age took a “voluntary permanent leave of absence” the airline offered to delay furloughs and layoffs. The retiring pilots will receive 50 hours of pay per month through age 65 and keep their benefits.

Coronavirus Relief Bill

The $2.2 trillion economic recovery bill that President Trump signed into law will temporarily prevent mass layoffs and furloughs at major domestic airlines through the end of September. About $50 billion is earmarked for passenger carriers, half in direct payments and the other half in loans and guarantees. The bill stipulates the companies have to use the grants exclusively for employee wages, salaries, and benefits. The companies also have to temporarily stop stock buybacks and dividend payments to receive the aid. The bill also provides $8 billion for cargo carriers, half in direct payments and the other half in loans, and $1 billion to $3 billion for the health costs of airline contract caterers.

In initial discussions on the relief package, Congressional Democrats wanted the airlines to purchase offsets for all of their carbon dioxide emissions in exchange for federal aid, but President Trump indicated that the relief package was not to add new costly requirements such as efficiency improvements or other “Green New Deal” provisions; it was to help regain the health of the industry.

Jet Fuel Demand

Global jet fuel demand has dropped by about 20 percent from its average of 7.5 million barrels per day. U.S. refineries produced about 35 percent less jet fuel in the last week in March compared to a year earlier. Gulf Coast jet fuel prices were at their lowest level seasonally since at least 2011, the earliest year that data are available. Some projections show that global jet fuel demand could drop by up to 70 percent, especially in the second quarter of 2020 as an increasing number of countries apply travel quotas to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Major oil companies including BP and Shell are preparing to take the unusual step of storing jet fuel at sea. Because jet fuel is sensitive to contamination and degrades more quickly than other refined fuels, after a few months, it cannot be used for aviation. The industry generally expects products will be used within three months of being produced. Storing refined products is more difficult than storing crude oil due to concerns about oxidation, stability, and moisture content.

The oil market could see a record build in supply in April that could overwhelm storage capacity within months. BP has provisionally booked the 60,000-tonne Stena Polaris tanker to store jet fuel for 40 to 60 days at a rate of $25,500 a day. Royal Dutch Shell has provisionally booked Torm Sara to store jet fuel for 90 to 120 days.

Some refiners are shifting to diesel because of the poor margins associated with jet fuel production. Diesel is currently more profitable and farmers stock up their supplies in the spring. A small amount of jet fuel can be added to diesel in crude distillation towers, which separates raw crude oil into products with different boiling points. Refiners can also choose to adjust their fluid catalytic cracking units to yield less gasoline and more distillate.

Conclusion

The airline industry is suffering from the coronavirus pandemic and may not be able to recover this year due to the uncertainty of containing the virus. As the coronavirus outbreak continues to spread across the world, countries impose further travel restrictions, and airlines continue to cancel thousands of flights, jet fuel demand will also be hit hard, requiring companies to employ unusual methods to store the fuel. The coronavirus relief package offers qualified aid to the airline industry with the intention of positioning it to meet the demand for travel that is pent-up in America and throughout the world when the coronavirus passes.