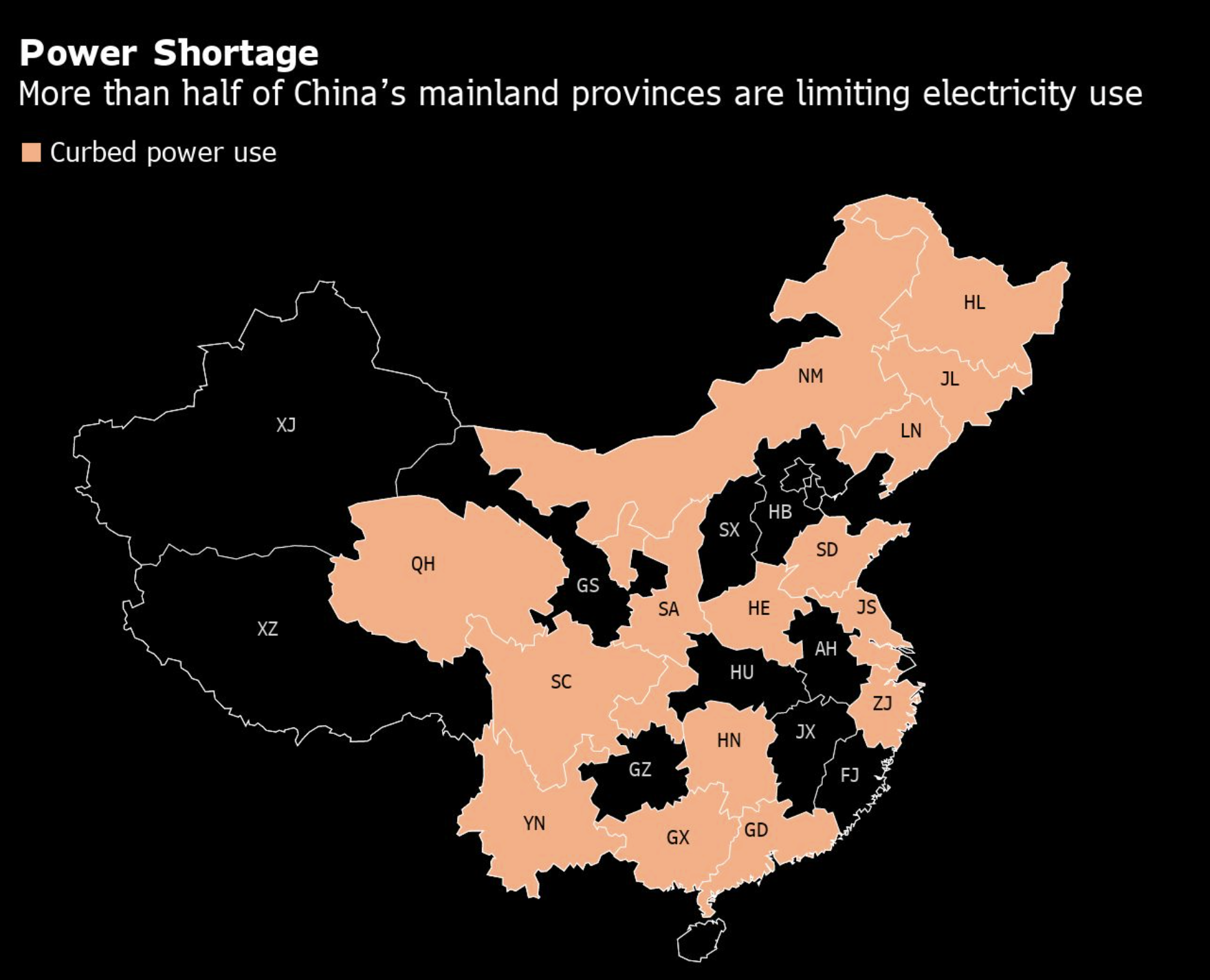

Recently, China’s Vice Premier Han Zeng ordered the country’s top state-owned energy companies to secure supplies for this winter “at all costs.” China is running low on fuels to get them through the winter, as is Europe. In China’s case, however, its energy crunch was mainly in response to a global surge in demand for consumer goods, many of which are produced in China. The result has been an increase in China’s electricity demand. Rather than upping production, however, China’s coal fired plants reduced production because they could not increase power rates commensurate with coal price increases, due to China’s official caps on electricity prices. This coincided with central government direction to reduce power plant emissions for the Beijing Olympics which begin in February. The resulting power crunch compelled multiple provinces in China to implement power rationing, with factory operation hours limited and power usage capped. Factories across various industries, including furniture, food and chemical production, had to suspend operations and reschedule production.

The price of coal in China surpassed 1,000 yuan (about $154) per metric ton, reaching a record high for the past 20 years, more than doubling costs. In the first eight months of the year, China’s power consumption went up 13.8 percent, while electricity capacity increased 9.5 percent. Aggravating the power crunch is a drop in renewable generation. For example, wind power generation in Liaoning fell to 70,000 kilowatt hours in September due to poor weather conditions, in contrast with the region’s installed wind power capacity of 10 million kilowatt hours.

China is making an all-out effort to ensure the nation’s power supply through better electricity pricing mechanisms and improved energy structures. Experts have called on the government to reform the sector to better reflect power costs, set higher electricity rates for peak hours, and further diversify its coal-based energy structure.

China’s National Development and Reform Commission urged the use of mid- to long-term coal supply contracts for power generators and heating suppliers in an effort to secure sufficient coal for the sector, especially for household use this winter. In late September, key power producers and heating suppliers in northeast China, where recent power outages occurred, signed supply contracts. The country’s top state assets regulator required key producers to ramp up coal production and scale up imports.

Trade Issues with Australia

Late last year, China stopped buying coal from Australia, which used to be the biggest exporter of coal to the country because Australia backed a call for an international inquiry into China’s handling of the coronavirus. As a result, China turned to Indonesia, Mongolia, Russia and other countries to make up for the shortfall. Last year, China signed a $1.5 billion supply deal with Indonesian coal miners. The irony, however, is that India, faced with an acute shortage of coal, purchased nearly 2 million tons of Australian thermal coal located in Chinese warehouses for months due to the tensions between Australia and China. Indian companies plan to buy more of the Australian coal from China. They are buying coal at $12 to $15 a ton discount compared to new shipments from Australia.

But now, China has decided to release Australian coal from bonded storage, despite the nearly year-long unofficial import ban on the fuel. An estimated 1 million metric tons of Australian coal (about one day of China’s coal imports) were in bonded warehouses along China’s coast, uncleared by customs, because of Beijing’s unofficial ban imposed last October. Although many cargoes had already been diverted to markets like India, some of the Australian coal started to be released domestically at the end of last month. The demand for coal had simply gotten too large to ignore millions of tons stored in China.

While China has urged top miners to boost output and told power operators to step up coal imports in “an orderly manner” to ease the supply crunch, it has refrained from directly resuming imports from Australia. In recent years, Australia has supplied an average of 85 million metric tons of coal annually to China, more than Canada’s yearly output. One-third to half of coal from Australia used to be exported to China.

Australia’s Newcastle thermal coal, a global benchmark, is trading at $202 a metric ton, three times higher than at the end of 2019. Global production of coal, which generates around 40 percent of the world’s electricity, is about 5 percent below pre-pandemic levels. Ramping up coal production can take nine months to get new mining trucks and even longer to install new equipment at mines.

China’s coal imports from other key suppliers, such as Russia and Mongolia, had been curtailed by limited rail capacity, while shipments from Indonesia had been hindered by rainy weather. That led some utility operators to recently import thermal coal from Kazakhstan. China’s first imports of U.S. coal were in June and July. China imported 197.69 million metric tons in the first eight months of 2021, down 10 percent for the year, despite August coal imports rising by more than a third. Coal imports from Russia roughly doubled year-over-year in the first eight months to 21 million metric tons. Coal from the U.S. quadrupled to 5.7 million tons in the period.

Conclusion

China’s power shortages are due to a combination of factors, including a shortage of coal, a flawed electricity pricing mechanism, the instability of renewable energy, and surging production activities due to increased demand resulting from the global economic recovery from coronavirus lockdowns. Also affecting power consumption is China’s public relations campaign to reduce coal generation during the lead-up to the Beijing Olympics. The supply problems related to the power crunch, however, has made China realize that it needs to make changes to provide more domestic coal production, institute mid- to long-term supply contracts for coal imports, and provide a better pricing mechanism for electricity. Despite releasing Australian coal in bondage at China’s ports to make up for their shortfall, China still refuses to import coal from Australia.