As I wrote in April at National Review, the global energy and emissions discussion has become too narrowly focused on China and the United States.

China is the world’s largest cumulative emitter, yes, and the U.S. is number two (with higher per-capita emissions), but other countries are, or will become, significant users of fossil energy as well.

The candidate for discussion that often comes up next is India, and rightfully so, as its enormous population and miniscule energy consumption augur significant emissions increases as it gets richer. But regularly overlooked is Southeast Asia.

Ten countries compose the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). They are, in order of population, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Singapore, and Brunei. Together they have a population that’s roughly double that of the United States.

ASEAN is a promising economic market, and it is one that is generally younger and less developed than China. Resultantly, it’s expected to experience faster economic growth than China over the coming decades at around 5 percent per annum.

ASEAN is sometimes divided into three economic cohorts: the rich group (Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore), the frontier group (Myanmar, Laos, and Brunei), and the emerging group (Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam).

The rich group—especially Singapore—is as developed as anywhere on the planet and is embarking on emissions reduction programs. The frontier group is at this point neither large enough nor developed enough to merit much attention. The emerging group, though, is where significant cumulative emissions increases from energy consumption are likely to occur.

The emerging group is made up of the region’s three largest countries. Indonesia has a population of 265 million, the Philippines has a population of 105 million, and Vietnam has a population of 95 million. For those keeping score at home, that’s almost half a billion people total.

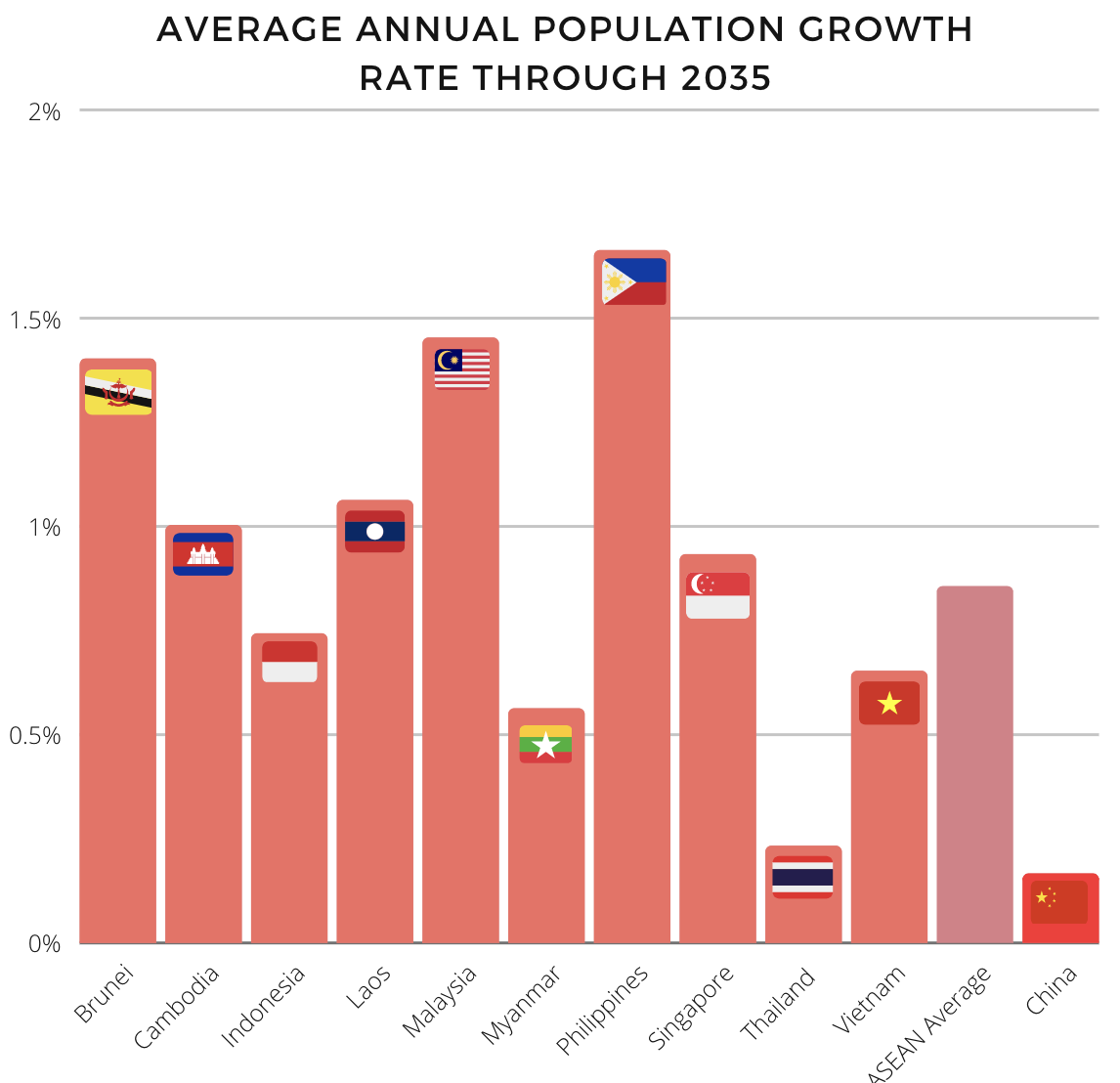

While China finds itself scrambling to avoid a demographic decline, Southeast Asia is still growing. The region puts up an average population growth rate of 0.85 percent annually through 2035, according to forecasts, which is at least five times higher than China’s, which in the early 2020s may already be negative.

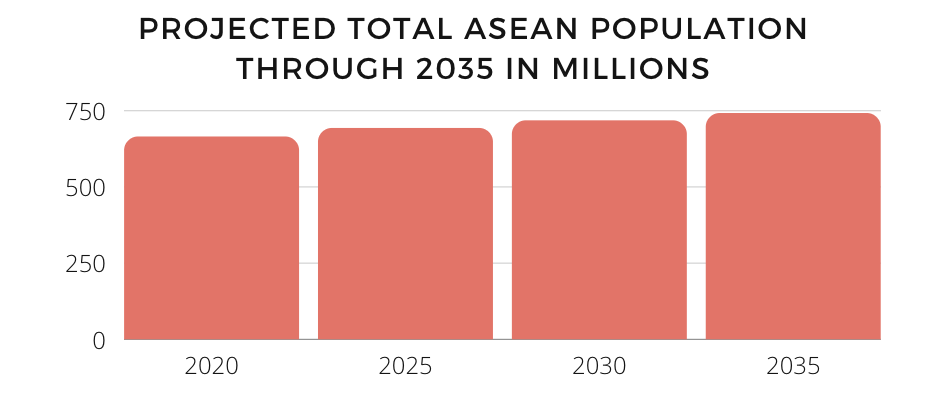

The ASEAN population is currently around 650 million—almost exactly half of China’s. By 2035 that figure could well be at 750 million.

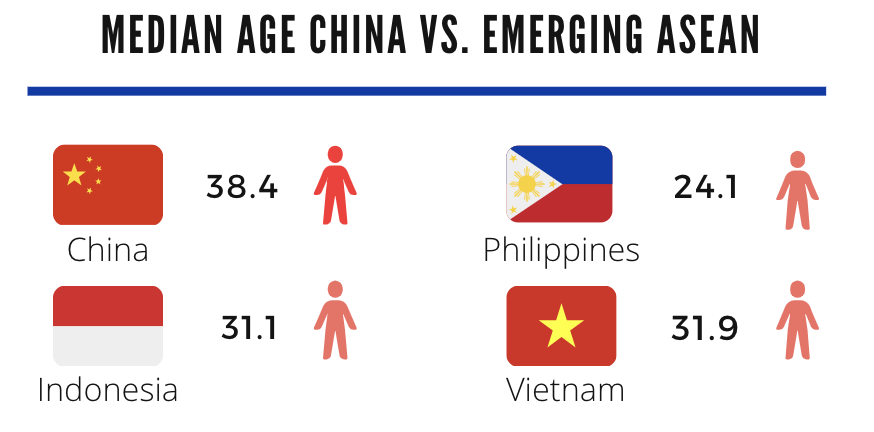

A big part of this story is that the emerging ASEAN cohort is younger than China’s population.

Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam had respective median ages of 31.1, 24.1, and 31.9 years of age in 2018, compared to China’s of 38.4. ASEAN will add 40 million potential workers this decade, while China’s WAP slips quickly into decline.

It is because of this emerging economic trio that the World Economic Forum (WEF) describes ASEAN as “on the cusp of a tremendous leap” in socio-economic progress.

According to the World Bank, 115 million Indonesians alone are poised to enter the middle class. As they do so, they will purchase more energy-intensive goods, like refrigerators, automobiles, air conditioners, and water heaters. This will add to a trend which has seen Indonesian middle-class consumption increase by 12 percent annually since 2002. In the Philippines and Vietnam, many of the same processes are underway.

Across all of ASEAN, WEF projects that there will be a regional near-doubling of high- and upper-middle income households, which currently number 30 million.

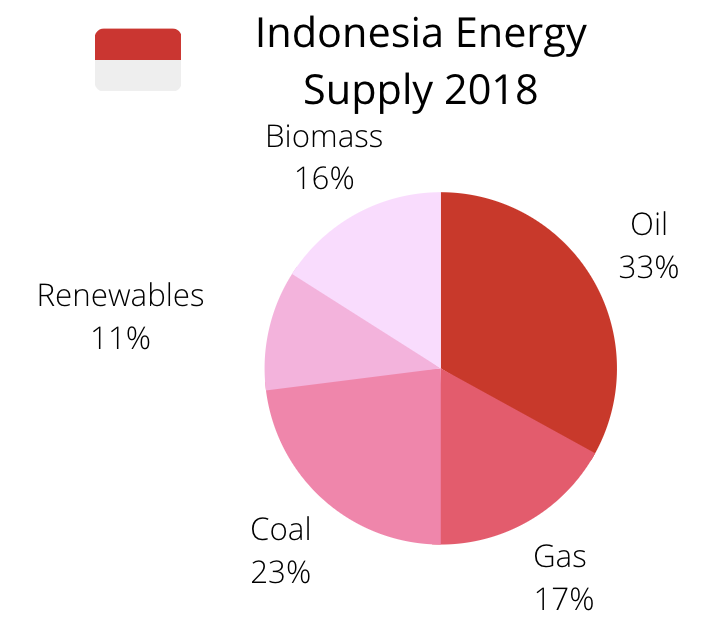

These economic and demographic trends indicate that the region’s energy consumption will rise. Because coal, oil, and natural gas are the region’s dominant fuel sources, emission will rise as well.

Indonesia gets about three-quarters of its energy from fossil fuels. Though at first blush, Indonesia’s production and use of biofuel would appear climate-beneficial, the country faces widespread international condemnation for the forest-clearance practices it deploys to produce the palm oil it turns into biodiesel. Further, Indonesia has been accused of polluting the region’s air with toxic haze from its forest fires. The emissions policy watchdog group, Climate Action Tracker (CAT), calls Indonesia’s plans highly insufficient for meeting Paris climate accord goals.

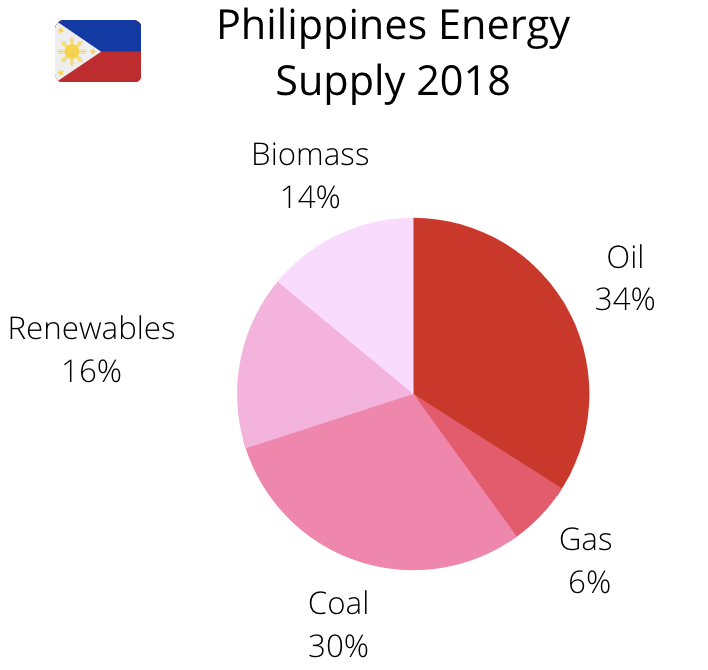

The Philippines gets almost two-thirds of its energy from oil and coal.

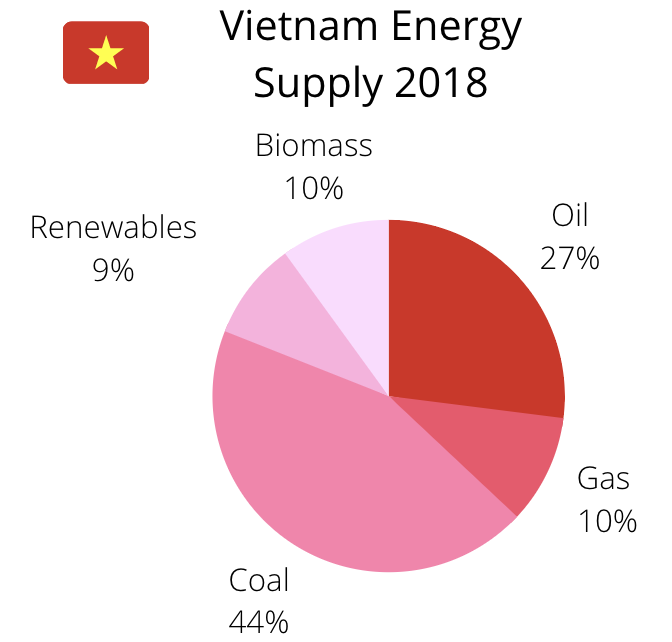

Vietnam uses coal for more than half of its electricity generation and three-sevenths of its total energy, with fossil fuels cumulatively making up four-fifths of it. According to CAT, Vietnam “lacks policy action for a green economic recovery, and has not focused efforts on emissions reductions.”

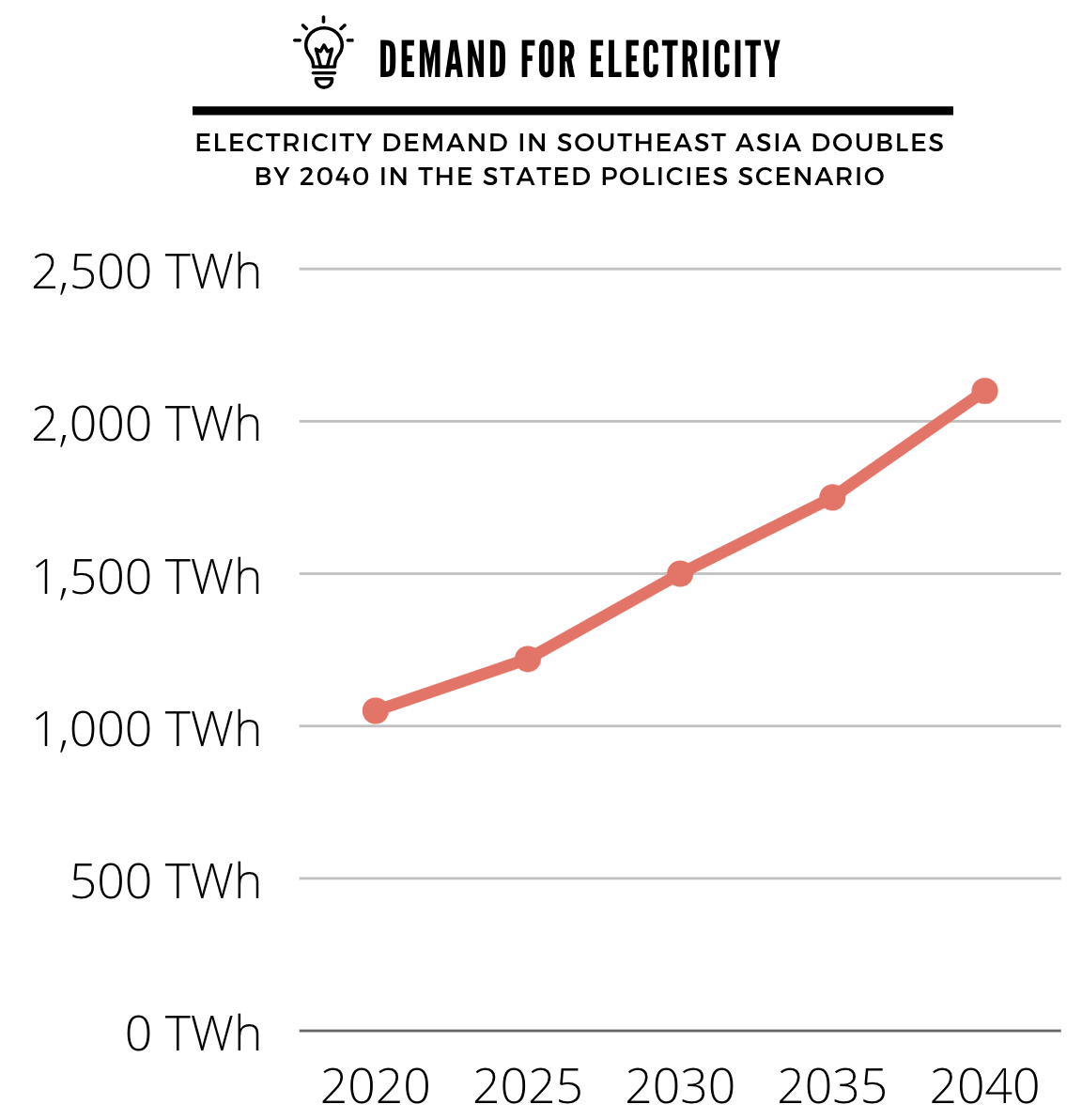

Led by Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, Southeast Asian electricity consumption will double by 2040, the International Energy Agency projects. Much of this new demand will be met by fossil fuel sources, contributing to significant emissions increases.

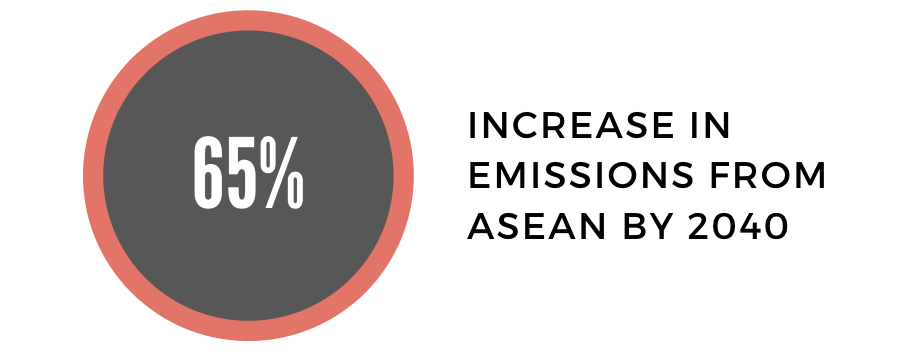

If the three emerging ASEAN countries follow similar energy patterns to reach levels of development comparable to Malaysia and Thailand it would mean a doubling of per capita emissions. Even in the stated policy scenarios (i.e., scenarios that may not be achieved) the International Energy Agency expects the Southeast Asia region to increase its emissions from around 1,500 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent to over 2,300 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2040.

China and the U.S. are the major players in energy and emissions (and just about everything else), but as this series of graphics shows visually, there’s more to the game than the world’s two titans.