As the world waits to see whether or not Israel and Hezbollah will adhere to the recently agreed upon (and already violated) cease-fire, it is important to analyze what threats remain and how further escalation could impact the regional war and global energy markets. Israel’s long-awaited retaliation for Iran’s October 1st ballistic missile barrage commenced well over a month ago on Saturday, October 26th. The attack involved precision strikes on approximately 20 targets, including several military installations where Iran produces fuel for their ballistic missiles and the air defenses over Iranian oil and nuclear facilities.

When Iran broke away from their traditional strategy of proxy warfare and attacked Israel with a barrage of 180 ballistic missiles from Iranian territory, they provided Israel with legitimate grounds for retaliation; Israel’s most recent attack on sovereign Iranian territory has now provided them with the same. Tehran declared that, “the response of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the Zionist regime’s aggression will be definitive and painful,” and, even though some time has passed, Iran’s Foreign Minister stated that, “[Iran has] not given up our right to react and we will react in our time and in the way we see fit.”

If Iran responds and attacks Israel, what that attack entails will leave Israel with the difficult decision of whether or not to adhere to their traditional defense policy, which calls for a disproportionate response aimed at making any further conflict prohibitively destructive for their adversary. If that happens, an Israeli disproportionate response could include more direct attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities and or oil fields and refineries, which could impact oil markets and threaten China’s industrial capacity since they remain Iran’s largest oil importer.

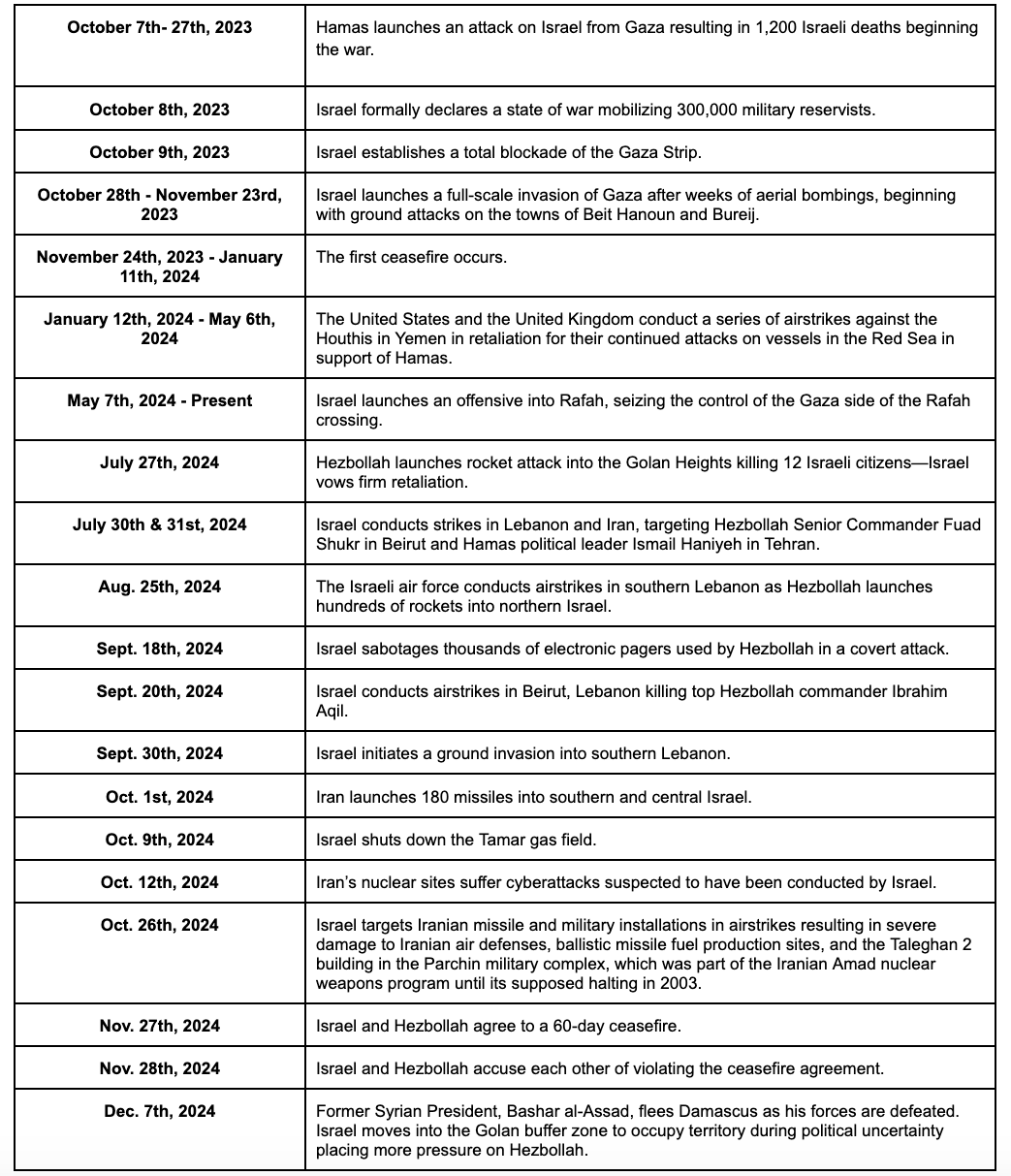

Timeline of Key Events of the Israel-Hamas War

Iranian Nuclear Program & Facilities

The Iranian nuclear program traces its roots to the U.S. Atoms for Peace program. It was initially developed to free up oil from its vast reserves to increase its global market share and export revenue. Beginning in 1953, after President Eisenhower’s speech to the United Nations announcing Atoms for Peace, the program began to allow for the lease of enriched uranium to mostly developing nations for non-military nuclear energy production. Iranian participation in the program began in 1957 and ended with the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The overthrow of the Shah of Iran led to the immediate end to the supply of American-enriched uranium, as the new theocratic totalitarian regime posed, and still poses, a direct threat to regional and global stability.

As of this year, Iran still has only one active nuclear reactor, Bushehr-1, with three under construction. Located in the port city of Bushehr, the reactor is operated by the Nuclear Power Production & Development Co. of Iran. Bushehr-1 has been commercially operable since September 2013, after construction was completed with the help of Russia. As of 2023, the reactor produces 915MWe of power per year and has produced a total of 58.03 TW.h of energy over its lifetime.

Any country that has enriched uranium has the basis for developing a nuclear weapon. This is the primary concern with Iran as they have remained a regional threat for decades—proven so by their consistent violent rhetoric and their direct involvement in the expanding Israel-Hamas war. Iran currently has two enrichment facilities, located in Natanz and Fordow, and has plans to install 6,000 new uranium-enriching centrifuges, significantly expanding their ability to quickly enrich uranium. Although Iran has relayed that they only intend to enrich to a low 5 percent, given the ongoing regional hostilities, the move has been met with concern. Support for the modern Iranian nuclear energy program came in part from the Joint Comprehensive Action Plan (JCPOA). Under this plan, Iran agreed to limit the extent of its nuclear operations and to open nuclear facilities to international inspections in exchange for extensive sanctions relief.

In January 2016, after the JCPOA was in place, the International Atomic Energy Agency confirmed that Iran had supposedly taken the necessary steps to ensure that its nuclear program would be entirely peaceful. At that time, Iran had a stockpile of enriched uranium and upwards of 20,000 centrifuges, which could have been used to make a total of 8 to 10 nuclear weapons at a pace of one weapon every 2 to 3 months. Currently, Iran is estimated to have 8,004 advanced centrifuges and has continued to produce 60 percent enriched uranium. Additionally, an anonymous diplomatic source disclosed to Reuters that, “these measures have no credible civilian justification and could, on the contrary, directly fuel a military nuclear program if Iran were to take the decision.” Furthermore, according to Rafael Grossi, head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 60 percent is a high enough percentage to create an effective nuclear device.

Citing the deal as being entirely one-sided and lacking any real mechanisms for ensuring regional peace, President Trump withdrew the United States from the JCPOA on May 18th, 2018. After implementing a series of harsher sanctions to pressure Iran back to the negotiating table, the Iranian economy was in a tailspin until President Biden’s administration began to ease up on sanction enforcement. Additionally, while speaking at the Aspen Security Forum in July of this year, Secretary of State Antony Blinken blamed the problem of the Iranian nuclear threat on President Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA, deflecting from the current administration’s lack of sanction enforcement, and claimed that, “instead of being at least a year away from having the breakout capacity of producing fissile material for a nuclear weapon, [Iran] is now probably one or two weeks away from doing that.”

The moment the Iranian regime acquires a nuclear weapon, the geopolitical calculus for power balancing and political leverage changes overnight. Engaging with a politically hostile and unpredictable nuclear power in a conventional military manner is both tactically and strategically illogical. This concern is part of the core reason why Israel would consider a disproportionate response targeting Iranian nuclear energy and research facilities. Decimating their capability to continue any form of nuclear research or uranium enrichment would be in Israel’s strategic interest since they are now engaged in a proxy war with Iran. Furthermore, it is in the geopolitical interest of the world that Iran does not acquire nuclear weapons because such an acquisition would be sure to set off a nuclear arms race in an already destabilizing region— Saudi Arabia would be highly likely to pursue a nuclear weapon rapidly upon Iran developing them.

Israel’s Major Gas Fields: Tamar & Leviathan

First discovered in 2009, the Tamar gas field is a natural gas field located in the eastern Mediterranean within Israel’s exclusive economic zone. With extraction beginning in 2013 and an estimated 10.2tcf of gas and one million barrels (mmbbl) of condensate as of 2023, Tamar has made Israel less of an energy net importer by producing 7.1 to 8.5 million cubic meters of gas per day. Accounting for 70 percent of Israel’s domestic gas demand, primarily for electricity production, Tamar has enabled Israel to be less reliant on coal and oil imports. Furthermore, after years of development, Tamar has also become a vital asset to Egypt which relies on substantial natural gas imports from Israel to sustain their severely impacted domestic market—shortages that continue to force rolling blackouts throughout the nation.

Israel’s Offshore Oil & Gas Fields

In addition to Tamar, Israel has control of its much larger neighbor, the Leviathan gas field. Discovered in 2010, Leviathan is the largest natural gas field in the Mediterranean and is estimated to hold 1.7 billion barrels of oil and 122tcf of technically recoverable gas. After years of construction and planning, resource extraction began in 2019 and has become a vital resource for Israel, Egypt, and Jordan. Like Tamar, Leviathan is located within Israel’s exclusive economic zone, and the combination of the two has significantly increased the nation’s political leverage in the region.

Leviathan Gas Field & Export Routes

Since the beginning of the war, production at Tamar and Leviathan has been shuttered twice, both from attacks or the threat of an attack—the latest taking place on November 5th with a drone attack near Tamar and the oil refinery in Haifa. The continued fighting has led Chevron, a majority shareholder of the Leviathan reservoir, to postpone the expansion of infrastructure until April 2025. Such delays will hinder much of the anticipated resource extraction, limiting Israel’s regional and global export potential, and compound Egypt’s current natural gas crisis, which has led to electricity shortfalls. As Iran weighs its options for retaliation, it is possible that either Tamar or Leviathan could be targeted given the importance that each plays in Israel’s domestic electricity generation, economic output, and diplomatic leverage.

Iranian Oil Production

Oil plays a key role in Iran’s economy and historically allowed the country to be one of the world’s largest energy producers and exporters. Although Iran is a member of OPEC, they, along with Libya and Venezuela, remain exempt from any agreed-upon production cuts due to the severity of sanctions and political uncertainty. Despite sanctions, Iran has some of the world’s largest proved reserves of oil and gas: Iranian oil reserves accounted for 24 percent of all oil reserves in the Middle East and 12 percent of global reserves. Even though it faced challenges from sanctions and regional instability, Iran was the fourth-largest OPEC producer of oil in 2023 and the third-largest natural gas producer in the world in 2022.

Heavy sanctions have limited Iran’s export potential, which is deemed necessary to hinder their funding of terrorist organizations like Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon, and the Houthis in Western Yemen. Sanctions have led them to export covertly to countries outside of America’s sphere of influence. Of the numerous refineries that Iran has, there are 10 of significance, the largest three being Isfahan, producing 370,000 barrels per day (b/d), Abadan, with 360,000 b/d, and Bandar Abbas, at 320,000 b/d.

Iran’s Oil Fields & Refineries

Before the expansion and enforcement of sanctions, in 2017, Iran had a diverse portfolio of oil importers including European nations, China, India, and South Korea. As of 2023, China is the main destination for Iranian oil importing, receiving an astounding 91% of all oil leaving Iran—this information is known primarily through ship tracking as none of Iran’s oil exports are cataloged transparently due to ongoing sanctions.

Targeting Iran’s oil production would certainly hurt their economy, since oil accounts for 40% of Iranian export revenue and 23% of overall GDP, however, it would also have the unintended consequence of disrupting China’s industrial capacity. As the majority purchaser of Iranian oil, China has become accustomed to the pleasure of purchasing heavily discounted oil from Iran and, although it does not account for the majority of Chinese imports, heavy sanctions on Iran and Russia have slashed the price of oil for those willing to circumvent sanctions to purchase it. For this reason, although China has begun shrinking its oil imports due to refinery capacity issues, losing access to discounted Iranian crude would force China to pay more from legitimate exporters or become more reliant on Russia for cheap oil. Either way, the negative impact on China’s industrial capacity would be of strategic value to the national security objectives of the United States as the Chinese Communist Party would most likely force manufacturers to absorb the higher cost of production due to their reliance on export revenue.

Conclusion

The ongoing Israel-Hamas war has, for the most part, been regionally contained. However, with direct Iranian involvement, the world is still waiting to see how Iran will respond to Israel’s latest retaliatory strike. Both Israel and Iran have vulnerable energy resources and infrastructure that, if damaged, would be detrimental to their respective economies. Israel has extensive natural gas reserves that Iran may decide to attack and Iran enjoys some of the largest oil reserves in the world that fuel a sizable portion of their economy. Any coordinated attack on these resources, regardless of the logistical difficulties, would be an extreme escalation of conflict and would have a high probability of engulfing the region in a direct war between Israel and Iran. Such a war would cause untold damage to the region, its inhabitants and allies, and the vital energy infrastructure that provides fuel to millions.