Recently, India asked its utilities not to retire their coal plants until 2030 and the country plans to institute an emergency law that will require maximum output at coal plants that use imported coal to prepare for record consumption expected this summer. Many Indian coal-fired plants have not operated at full capacity in the recent years because of competition with power generated from cheap domestic coal. Federal power ministry officials intend to work with those involved in debt restructuring of financially stressed power plants to make them functional. India expects its power plants to burn about 8 percent more coal in the financial year ending March 2024 because increased economic activity and erratic weather is expected to continue to increase power demand. India still has tens of millions of people lacking electricity. In 2022, people living without electricity worldwide is expected to have increased by 20 million, reaching 775 million.

Due to expected high electricity demand, India asked utilities to not retire coal-fired power plants till 2030, just over two years after committing to eventually phasing down its use of coal. Last May, India indicated that it plans to reduce power generation from at least 81 coal-fired plants over the next four years, but the proposal did not involve shutting down any of its 179 coal power plants. India has not set a formal timeline for phasing down coal use and this move indicates it will not happen soon.

The Central Electricity Authority (CEA) advised all power utilities not to retire any thermal (power generation) units till 2030 and ensure availability of units after performing renovation and modernization activities. The CEA, which acts as an advisor to the ministry, cited a December meeting where the federal power minister had asked that aging thermal power plants not be retired, and to instead increase the lifetime of such units considering the expected electricity demand.

India is the world’s second largest-consumer, producer and importer of coal, which accounts for nearly three-quarters of its annual electricity generation. Power demand in India surged in the recent months due to extreme weather, rising household use of electricity as more companies are allowing employees to work from home, and a pickup in industrial activity after easing of coronavirus-related restrictions. Peak power demand rose to a record of 210.6 gigawatts on January 18, 1.7 percent above the previous peak of 207.1 gigawatts at the height of an intense heatwave last April that caused India’s worst power crisis in six and a half years.

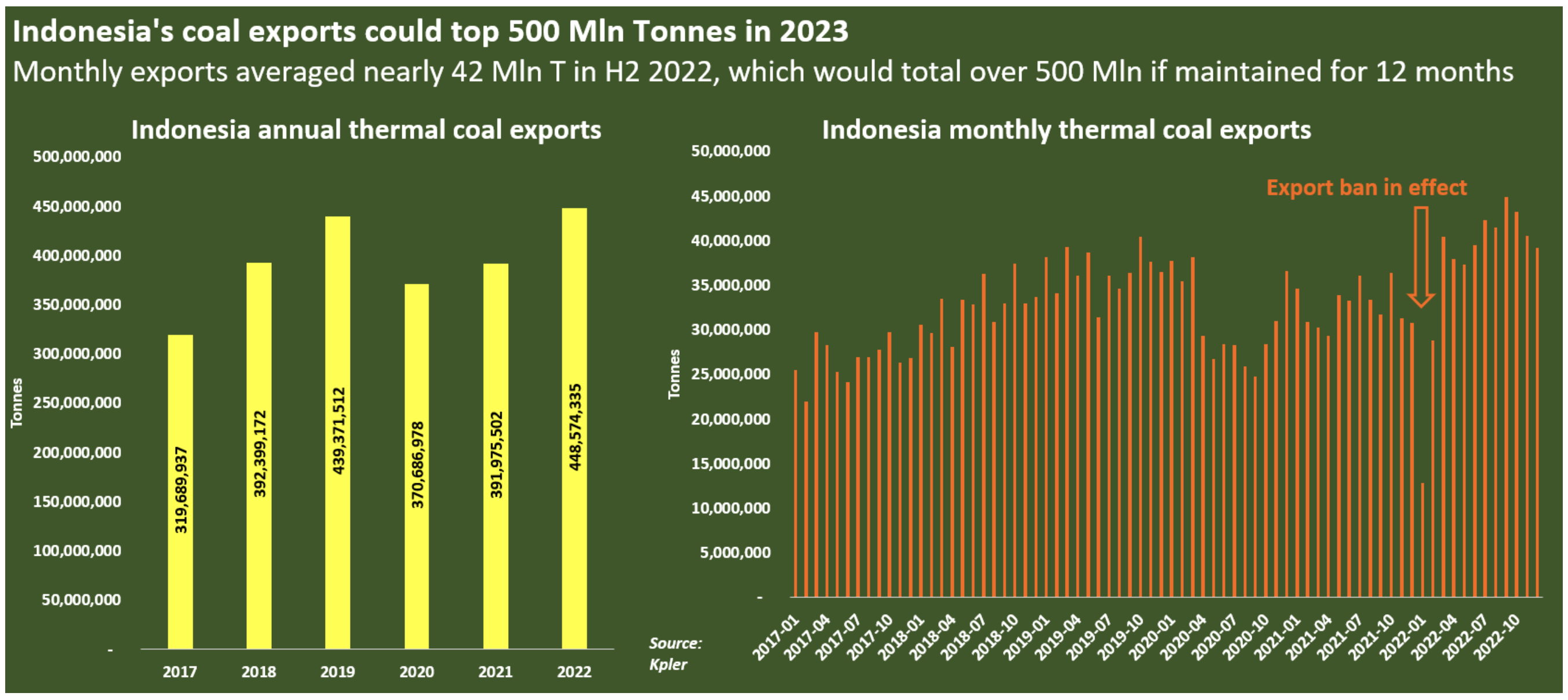

India’s utilities will likely need to increase coal imports this year due to the demand surges, which have made worse by freight bottlenecks that are disrupting domestic coal supplies. India’s coal-fired plants may have to increase imports by 50 to 60 percent from April to December 2023 to “avert a possible crisis.” India depends on imports for nearly a quarter of its coal supplies, 65 percent of which came from Indonesia in 2022. India’s increased buying on the world coal market along with top importer China, who is ramping up industrial activity after it eased its COVID 19-related restrictions, could help increase global coal prices that cooled mainly due to a warmer-than-expected European winter.

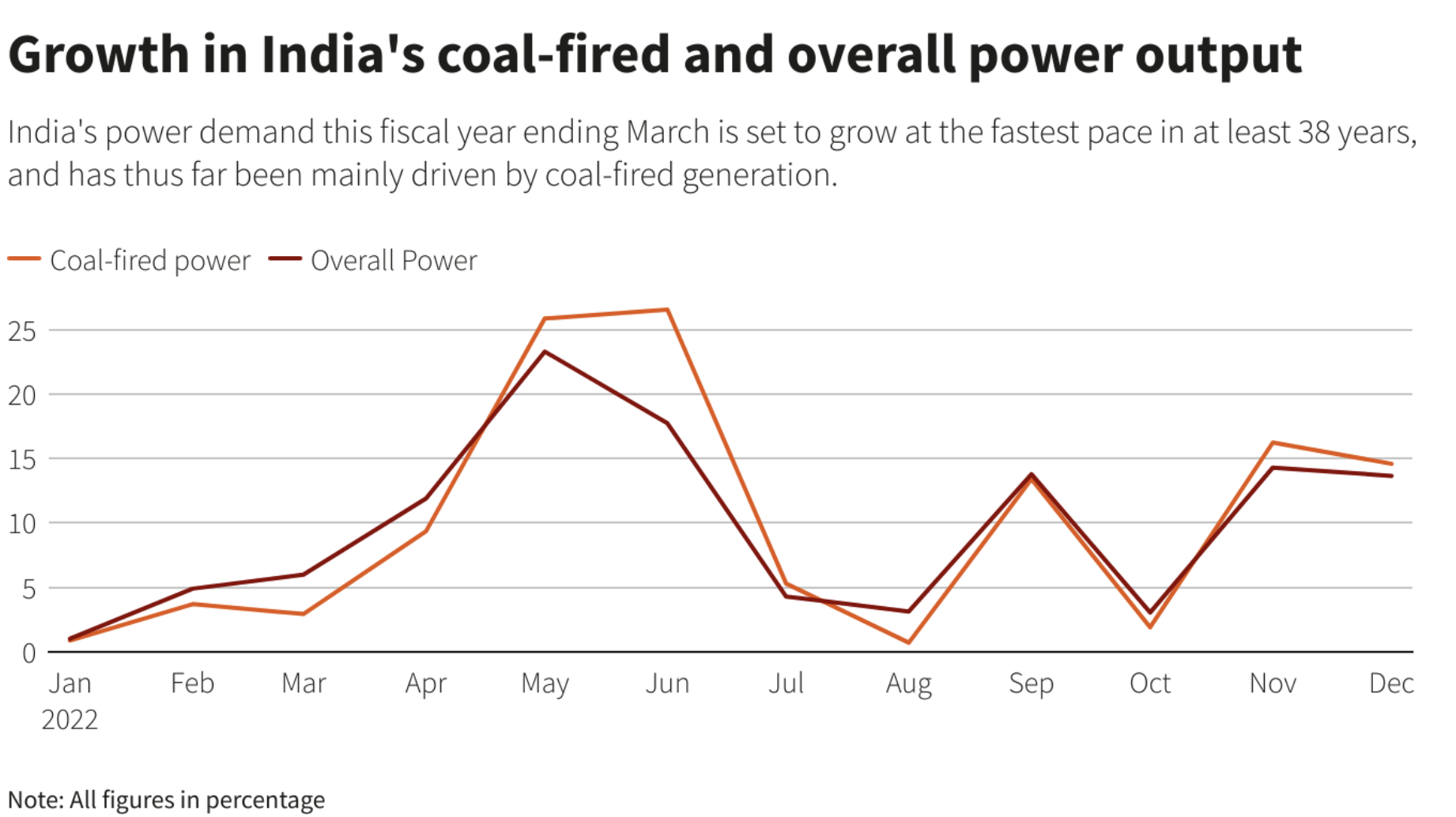

India is one of the best economic performers among the G20 nations and its industrial activity has driven increases of around 14 percent in electricity generation in November and December versus average annual growth of 9.6 percent. Coal-fired generation accounted for most of the increase, rising about 15 percent during the two months.

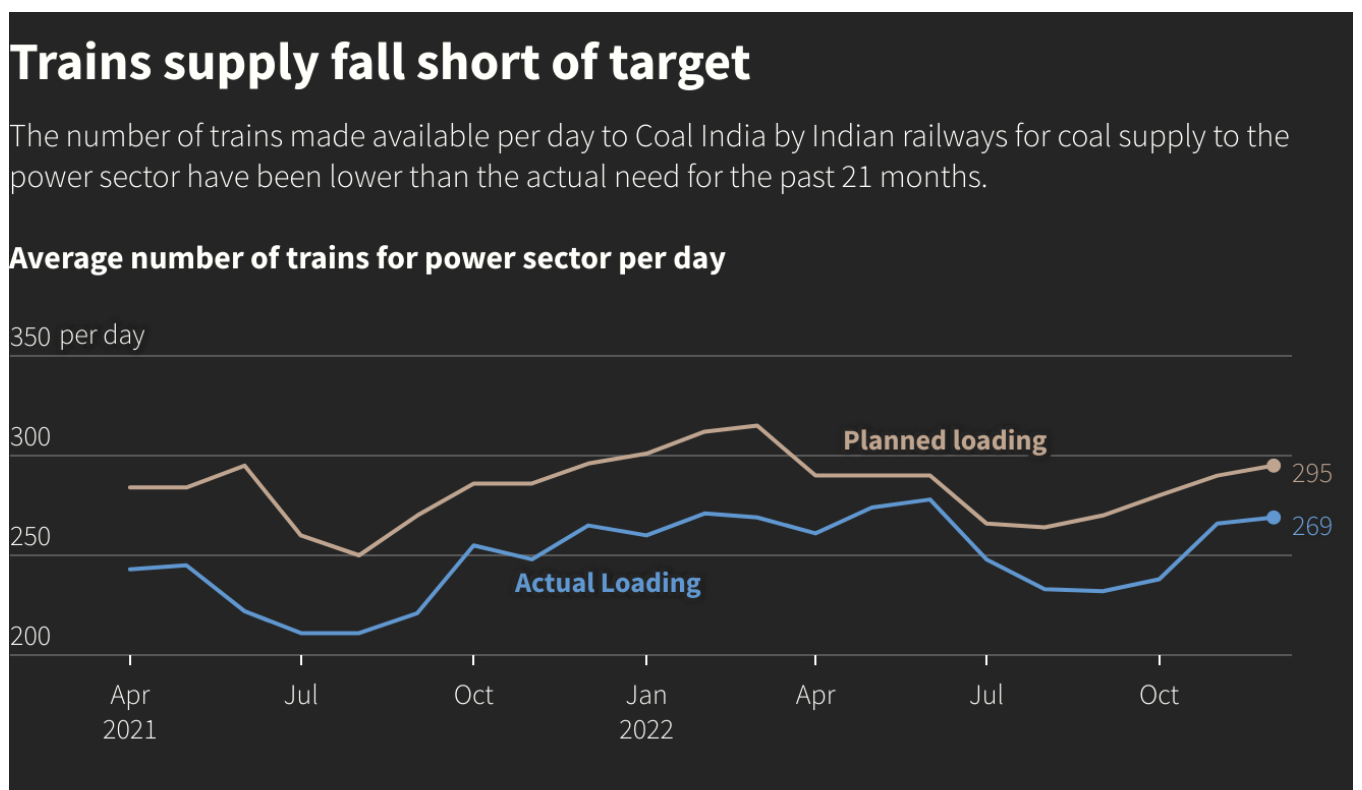

While India increased its domestic coal production, it is still having problems keeping the amount of supply at utilities to the 24-day standard the government wants. The supply at utilities is at 12 days now. Part of the problem is rail car shortages. Trains made available by the Indian Railways to Coal India, which produces 80 percent of India’s coal, have fallen short of monthly targets for at least 21 months despite increasing the number of trains supplied each day.

Indonesia’s Record Coal Export Sales

For 2022, total Indonesian thermal coal exports hit 448.5 million metric tons–a record number that was 56 million metric tons (14.4 percent) higher than the total for 2021. The world’s top thermal coal exporter temporarily banned coal exports a year ago to protect domestic power producers, sending coal prices soaring and kicking off a volatile year for coal and other power fuels. But since then, Indonesia has set a new record pace for shipments that if sustained puts it on course to be the first country to surpass half a billion metric tons of coal exports in a single year. Indonesia’s surprise coal export ban on January 1 last winter forced major importers to scramble for replacement supplies from other exporters such as Columbia, South Africa and Australia. But, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine enabled Indonesia to regain its footing in the coal export market.

Conclusion

India intends to use coal at its electric utilities for at least this decade, despite the push by Western countries to phase out coal use. The country has told its utilities to not shutter any plants before 2030 and has instituted an emergency law that allows coal plants dependent on coal imports to ramp up their output. While India has pushed its domestic coal industry to produce more, higher electricity demand and freight train car shortages have resulted in increased dependency on coal imports. India wants its country to continue to grow economically and realizes it cannot do that without continuing to use its coal plants. While the country is adding wind and solar power, it fell short of its 2022 renewable energy addition target by nearly a third because there is a disconnect between government targets and various operational, financial and regulatory constraints. Also, China is considering reducing exports of solar chips which could further affect India’s solar manufacturing.

Goals and government policies and regulations must be in sync for lofty targets to be met. The Biden Administration is having the same problem with meeting its goals after blocking the Twin Metals mine in Minnesota and the Pebble mine in Alaska that could produce much of the copper and other critical minerals needed for its electric vehicle program and renewable energy technologies. Now that governments have begun to control energy policies, it will be important for people to scrutinize the differences between their plans and their performance. In India, available, reliable and affordable energy seems to be the priority.