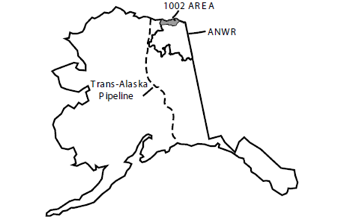

In the 1970s, the United States built the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) to provide greater access to large reserves of domestic oil in Alaska. Built at a cost of $8 billion (equal to over $39 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars), TAPS moves oil 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope to Valdez, a southern port in Alaska.[i] Thirty-three years after start-up in 1977, the pipeline, originally designed to move 2.1 million barrels per day, has a current flow of only 0.68 million barrels per day[ii], less than a third of its capacity due to the production decline at oil fields in Prudhoe Bay and other North Slope areas. There are far more domestic oil resources that could flow through the pipeline, but the federal government continues to deny Americans access to these energy resources.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), for example, could be producing oil but for U.S. government actions to prohibit drilling there. The U.S. government in its wisdom is also not allowing drilling in offshore areas of Alaska. Recently, Shell Oil was not able to garner the final of 35 permits to drill for oil in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Alaska. At the same time that Shell was denied a drilling permit by the U.S. Government, Russia is making deals with oil companies to drill for oil off its coast in the Arctic Ocean.[iii]

Alaska’s Oil Resources

Prudhoe Bay and surrounding oil fields. The Prudhoe Bay oil field is located on state lands 400 miles north of Fairbanks, Alaska, and is the largest oil field in the United States.[iv] It was originally estimated to contain 25 billion barrels of oil. Production started in June, 1977 at the completion of TAPS. Production from Alaska’s North Slope peaked in 1998 at 2 million barrels per day, and has since fallen to less than a third of that amount. It is expected to decline further, falling below 0.3 million barrels per day by 2030, according to forecasts from the Energy information Administration.[v]

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). ANWR is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska consisting of 19.3 million acres on Alaska’s North Slope. It was first protected by the federal government in 1960 by president Dwight D. Eisenhower, but allowed oil and gas activities. Currently, ANWR requires Congressional approval to drill for oil.[vi] In 1980, 1.5 million acres of ANWR was designated as the “1002 area” and estimates of its natural resources were mandated. The U. S. Geological Survey conducted surface and seismic exploration and estimated that ANWR contains 10.4 billion barrels of oil and 8.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.[vii] Congressional approval was granted in 1995 to drill in the 1002 area, but vetoed by President Clinton as part of the 1995 budget controversy that led to a government shutdown.[viii] Opponents of exploration are concerned with the possible harm that finding and developing oil may have on natural wildlife, particularly on migration of caribou. The drilling experience in Prudhoe Bay, however, has shown it to have negligible impact. Based on the Alaska Fish and Game’s census, the Central Arctic Caribou Herd’s numbers in the Prudhoe Bay fields have increased from 5,000 in 1977 to 31,000 in 2002 to approximately 67,000 in 2009.[ix]

Senator Lisa Murkowski is introducing two different bills to allow oil production from the 1002 area of ANWR. One of the bills would require the government to lease 200,000 acres of the area for infrastructure including roads, pipelines, drilling equipment and other facilities within two years of the bill’s passage. Revenues from oil production would be used for environmental mitigation, federal deficit reduction, renewable and alternative energy development, and for environmental programs. The second bill would allow oil and gas production from the coastal plain through directional drilling from facilities on state lands bordering ANWR.[x] Alaska’s Don Young, the sole representative for Alaska in the House of Representatives, has introduced a similar bill to allow drilling on ANWR’s 1002 area.

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A). The NPR-A is a 23 million acre area (about the size of the State of Indiana) in northern Alaska that contains an estimated 10.6 billion barrels of oil. In 1923, President Harding set aside this area to be used as an emergency oil source for the U.S. Navy. In 1976, the administration of the reserve was transferred to the Bureau of Land Management in the Department of the Interior. While the BLM has held lease sales for oil production in the NPR-A, no oil is being produced there because of lawsuits filed by environmental organizations and the need for a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to construct a pipeline. Because the oil deposits in the NPR-A are spread out over its 23 million acres, drilling for oil in ANWR where the oil resources are concentrated would be more economic and probably should be pursued first.[xi]

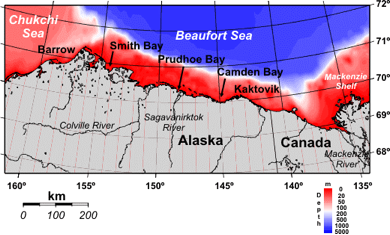

Offshore Alaska and Arctic Ocean areas. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated the amount of oil and natural gas in areas north of the Arctic Circle in 33 geological provinces. The mean estimates of the oil and gas resources in those 33 provinces total 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids, of which 84 percent is in offshore areas. [xii] Alaska’s outer continental shelf is estimated to contain 25 billion barrels of oil, approximately equivalent to the reserves of Angola, a member of the Organization of Petroleum Producers.[xiii] However, it is important to note that very few areas offshore Alaska have been explored, and therefore, the estimates could be smaller or much larger.

Shell had plans to drill for oil in the Beaufort Sea off Alaska’s northern coast, but the final air permit issued by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was appealed to the Environmental Appeals Board by environmental groups and the board overruled the EPA, invalidating the permit.[xiv] The company has invested more than $3 billion in exploration off the coast of Alaska in the Beaufort Sea and paid $2.2 billion for leases off the northwest coast of Alaska in the Chukchi Sea. Shell was planning to begin drilling in 2010, but its efforts were suspended after the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in April when the government put a moratorium on offshore drilling. Its current problem with obtaining permits from EPA has made the company suspend its drilling program offshore Alaska until at least 2012 when it hopes to procure the necessary final permit. Moving the equipment and making other necessary preparations would cost more than $100 million for a season (105 days) of energy exploration.[xv] According to Alaska Senator Mark Begich, “Their foot dragging means the loss of another exploration season in Alaska, the loss of nearly 800 direct jobs and many more indirect jobs. That doesn’t count the millions of dollars in contracting that won’t happen either at a time when our economy needs the investment.”[xvi]

A new study has estimated the economic effects of producing the nearly 15 billion barrels of oil in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas over a 50 year period to generate an average of 54,700 new jobs; 91,500 jobs at peak employment; $145 billion in payroll; and $193 billion in government revenue based on $65 a barrel of oil. Government revenues reach $263 billion when oil is priced at $100 a barrel, closer to today’s market price. The study also predicts that oil development in the Arctic would decrease our reliance on imported oil by 9 percentage points over a period of 35 years from its current level of 60 percent, increasing greatly our national security and moving closer to energy security.[xvii]

In the House of Representatives, Representative Don Young of Alaska added an amendment to the federal spending bill for 2011 that would prevent EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board from blocking air pollution permits needed for offshore drilling. The amendment states that no funds in the bill “may be used by the Environmental Appeals Board to consider, review, reject, remand, or otherwise invalidate any permit issued.” Shell’s permit was remanded in a decision by the board last December. The vote was 243-185 in the House, but the Senate and the President must also agree, a task much harder to achieve.[xviii]

Meanwhile, Russia has signed a deal with BP to explore its Arctic waters, and other western companies are pursuing oil interests in Russia as well. BP’s joint venture with Rosneft, Russia’s state-owned oil company, covers exploration in three sections in the Kara Sea, an area north of central Russia. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the Arctic holds one-fifth of the world’s undiscovered, recoverable oil and natural gas, with 43 of the 61 significant Arctic oil and gas fields located in Russia. The Russian side of the Arctic is rich in natural gas, while the North American side is richer in oil.[xix]

Russia is not alone in exploring for oil and gas in the Arctic. Norway is preparing to open new Arctic areas for drilling and Greenland has already begun exploratory drilling with a Scottish firm and other western countries are expected to take part in drilling off Greenland’s coast in the next few years.[xx]

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS)

TAPS has transported over 15 billion barrels of crude oil[xxi], but because it is now carrying oil at about a third of its capacity, increased risks of corrosion and leaks can be expected according to experts.[xxii] Some experts have estimated that flows down to 200 to 300 thousand barrels per day[xxiii], which the Energy Information Administration expects it to reach within 20 years, would be the minimum for viability. But even levels below 600 thousand barrels per day would require modifications to make the pipeline economically viable to maintain oil production. And further modifications would be needed once flows reach 300 thousand barrels per day because it would result in a greater decrease in oil temperature, causing an increase in oil viscosity and wax problems that are expensive to correct. Obviously, the determination of when TAPS would no longer be viable is when the costs of maintaining and refurbishing it are no longer counter balanced by the economics of the oil it carries.[xxiv]

Conclusion

Countries around the world are investing in oil exploration in offshore and Arctic areas while the United States government has virtually shut down new oil exploration citing safety and environmental concerns that are making them withhold leases and permits. These issues are not stopping Russia, Norway, Greenland and other countries, who know that jobs and economic growth are based on their oil resources.

Alaska holds over 45 billion barrels of oil, over twice our current oil reserves[xxv], that are just waiting for approval to drill from the Department of Interior and/or the EPA. Those 45 billion barrels – worth a staggering $4.5 trillion at today’s prices — would provide over 6 years of oil for this country if it were all used at once to satisfy U.S. oil demand, but in reality it would be spread over many more years of productive use. The $4.5 trillion would be spent at home, rather than abroad, helping adjust the balance of trade with the rest of the world. In fact, the underutilized capacity in TAPS is enormous, more than the oil produced in Texas. [xxvi] If TAPS were run at full capacity today, oil imports would be reduced by over $51 billion per year at $100 per barrel.

While our government is putting new requirements on oil exploration and effectively banning companies from producing new oil to transport to US consumers, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System is in a critical situation where its viability is dependent on oil flow which is quickly dwindling from oil resources on Alaska’s North Slope. Because it takes 5 to10 years to get through the permit process and to start producing oil, action is needed now. The longer the government waits to allow energy jobs and development to add supplies to the pipeline, the greater and longer the threats to American energy, economic and national security.

For Sources, please download the following PDF: U.S. Government Shuts Out Increased Alaskan Oil Production