As crude oil prices continue their upward march, American motorists are understandably anxious to know the reasons. In previous posts I have explained the role of the Federal Reserve’s loose monetary policy. Yet another significant part of the story is the world’s spare oil capacity—which can become razor-thin when supply is disrupted in volatile regions such as Libya.

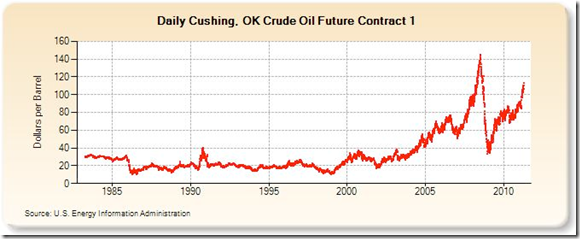

Oil Flirting With Previous Highs

As the chart below shows, oil prices are on their way to surpassing the previous peak set back in the summer of 2008:

No one knows the future, and the trend may of course reverse itself, particularly if the global economy should fall back into recession. Yet most analysts predict that oil prices will continue to rise (as they typically do) into the summer months, possibly surpassing the record levels of $145 a barrel (for a futures contract) set in July 2008.

The Significance of Spare Oil Capacity

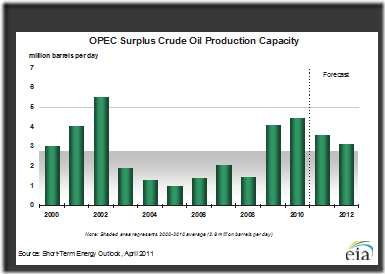

Industry analysts often use the metric of spare oil capacity as an important factor in price movements. The following chart from EIA shows the surplus crude oil production capacity of OPEC nations, which is effectively the spare capacity of the entire world (since other major producers are operating nearly at full capacity):

The fit is not perfect—there are obviously other influences at work—but the chart of spare capacity mirrors the first chart of oil prices. After the dot-com recession began in the early 2000s, oil prices dropped and spare capacity increased. Then by 2003 the economy had picked up steam, leading to rising oil demand, falling spare capacity, and higher oil prices. From 2005 – 2007, spare capacity increased somewhat, and oil prices oscillated in a narrow band. But then in 2008, spare capacity began dropping again, which occurred as prices skyrocketed. As the global economy went into severe recession in late 2008, prices crashed and spare capacity shot way up again. Now, the trends are going the other way, with prices rising and spare capacity falling.

An important qualification to the EIA graph of spare production capacity is that it is calibrated in absolute physical amounts—millions of barrels of oil per day—when the economically relevant figure is spare capacity relative to world consumption.

For example, the EIA’s estimated spare capacity for 2010 is slightly higher than the figure for the year 2001. On the face of it, this might suggest that oil prices (adjusted for price inflation) should have been lower in 2010 than they were in 2001.

However, we need to account for the fact that world oil demand grew strongly over the past decade. In 2001, world oil production was 77.7 million barrels per day. By 2010, average daily oil production had grown to 86.3 million barrels per day.[1] Thus a safety margin of a particular number of barrels per day in spare capacity would be less reassuring in 2010 versus 2001.

The Danger of Disruption

With the world as a whole operating on a fairly tight margin, market prices are pushed upward to reflect the dangers of imminent supply disruptions. For example, many analysts attribute some of the recent price hikes in oil to the disturbances in the Middle East.

In the abstract, Libya’s 1.7 million barrels per day of output might seem too small to induce large swings in world oil prices. But Libya’s output represents more than a third of the world’s total spare capacity. Even more sobering is the fact that Iran’s daily output of more than 4 million barrels per day translates to more than 90 percent of the world’s spare capacity.

In short, the world oil market can handle one major disruption in supply from the volatile Middle Eastern producers (Iran, Iraq, Libya, etc.), but only one. Beyond that, the world would be physically incapable of producing enough barrels of oil to satisfy the current levels of consumption. In such a scenario, the market price of oil would have to rise very sharply in order to ration the available barrels among potential buyers.

Because the production and consumption margin are so thin, the market price has already risen as the situation unfolds in the Middle East. Although people decry “the speculators” for making gasoline more expensive, this is exactly what we want markets to do. The higher price brings forth supplies from other sources, and it leads to lower current consumption allowing for the build-up of inventories.

What Policies Can Help?

If the problem is that world oil production is having a hard time keeping up with growing demand, then one obvious solution is to remove government constraints on further development of oil resources. There are many billions of barrels of oil that could be extracted from regions controlled by the U.S. federal government, if only it would give producers the green light.

What of policies designed to limit consumption? Should the government impose taxes on gasoline, or give subsidies to non-petroleum fuels, in an effort to reduce the world demand for oil?

From an economic perspective, the answer is no—this would be a cure worse than the disease. Market prices automatically ration the available quantity of oil to the people who want to use it. The purpose of opening up ANWR and the Outer Continental Shelf to development is that doing so would make petroleum fuels more affordable for consumers.

In contrast, the government doesn’t help consumers by artificially making gasoline use even more expensive (through tax hikes), or by taking funds from where private investors would put them, and instead channeling them into unprofitable “green” energy lines. After all, Americans always have the “option” of not using gasoline and other petroleum-based products, if they become too expensive. The government doesn’t do them any favors by forcing them to restrict their use.

Conclusion

The inexorable rise in the world demand for oil, coupled with the political upheavals in the Middle East, underscore the narrow margin of spare production capacity. If policymakers want to ease this situation—and thereby take pressure off of oil prices—they should remove legal and regulatory obstacles to further oil production.

[1] Oil production data are available (after adjusting the settings) at this interactive EIA table.