New England has become heavily dependent on low cost natural gas, which accounts for about half of its power generation as the region has retired many of its coal and nuclear plants. However, because of a lack of natural gas pipelines, New England has difficulty getting sufficient supplies of natural gas from nearby areas, such as the Marcellus Shale formation, especially during the winter months. This past winter, the region had to use dual-fuel power plants, consuming about 2 million barrels of oil during January’s deep freeze, which is over twice the oil consumed in 2016, according to the Independent System Operator for New England. Because the demand for natural gas is growing faster than the infrastructure to deliver it to the region is, electricity prices will need to increase. As it is, the six New England states have the highest regional electricity rates in the lower 48 states—53 percent above the national average. If the infrastructure constraints remain in place, electricity consumers can expect a good deal of price volatility during the winter months.

The Winter Cold Spell

Due to the lack of pipeline infrastructure for natural gas and the preference given to home heating, the generation mix on the grid shifted heavily to oil. On December 24, 2017, oil supplied just 2 percent of the region’s electricity. On January 6, 2018, oil provided 36 percent of the electricity.

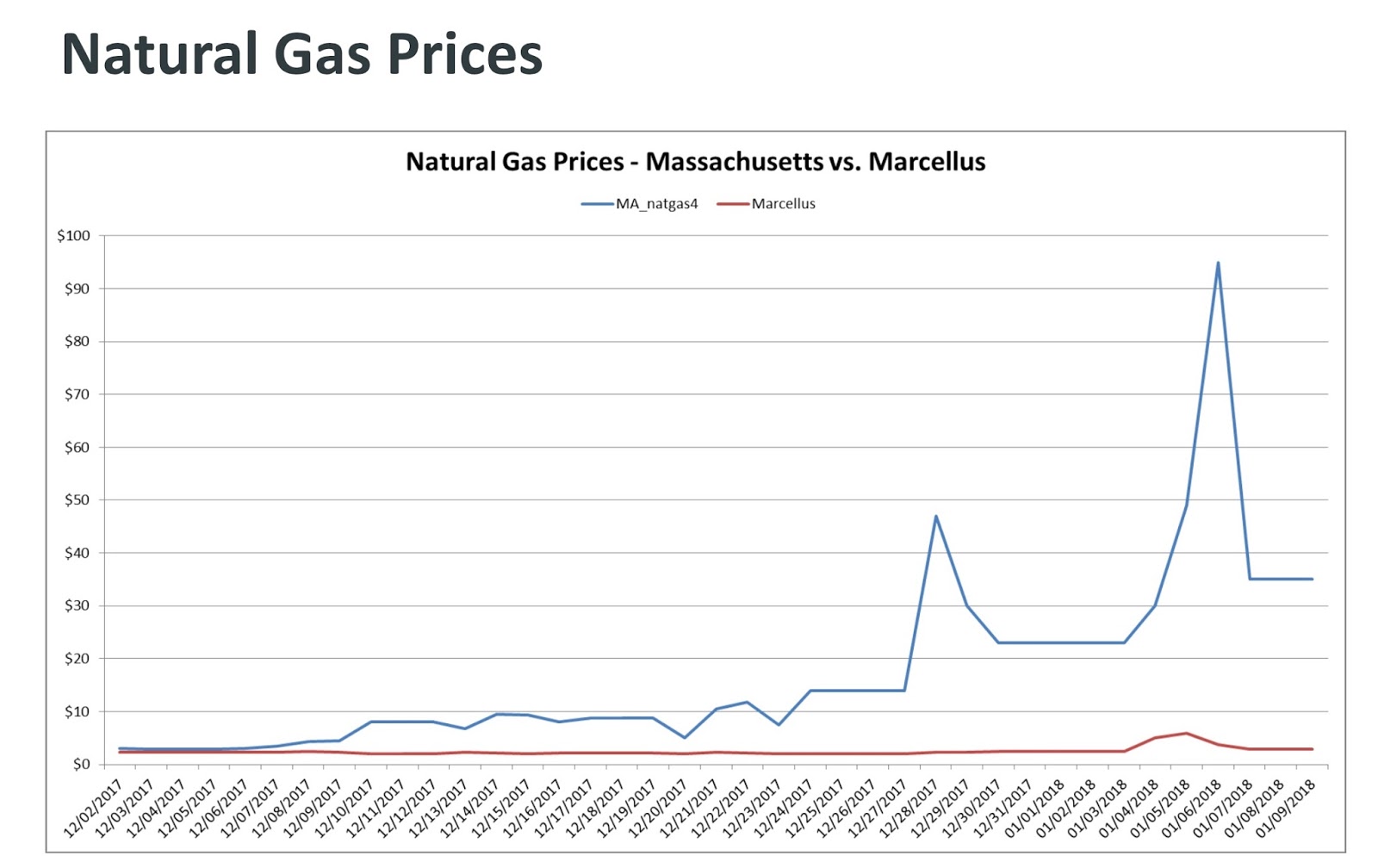

As the graph below shows, during the cold spell, natural gas prices in Massachusetts were vastly higher than the Marcellus Shale prices, which remained fairly steady. Natural gas prices delivered to electric utilities rose about 30 fold (from around $3 per thousand cubic feet to around $90).

Electricity prices followed the trajectory of natural gas prices, but the impact was less severe since generators that could switch to oil did switch when oil became less expensive than natural gas. Due to power plants using the lower-priced oil, electricity prices increased from around $50 per megawatt hour to around $450 per megawatt hour—a nine-fold increase.

However, the region was burning oil far faster than it was replenishing it. On December 1, the region had 68 percent of the maximum oil available to power plants. On January 8, the region had just 19 percent. (See graph below.)

NIMBYism (Not-In-My-Backyard) in New England

In New England, it is very difficult to build energy infrastructure. Major proposed natural gas pipelines have been shelved, including Kinder Morgan’s Northeast Energy Direct and Spectra’s Access Northeast, due to financial and political challenges. Further, New Hampshire’s Site Evaluation Committee rejected the Northern Pass power line project in February, which would import low cost hydroelectric power from Quebec to New England.

All New England states have renewable portfolio standards, requiring utilities to obtain an increasing amount of electricity from renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. Massachusetts, the region’s most populous state, has a 40 percent mandate for renewable energy by 2030. Yet, policymakers in the region have blocked projects that could help meet those targets, such as the Northern Pass power line noted above. Massachusetts wanted to use hydroelectric power from Northern Pass to help meet its renewable portfolio standard.

One Approach to Pipeline Constraints: Supersizing

The concept of supersizing pipelines is beginning to take hold in the United States and Canada to address infrastructure constraints. A larger pipeline along the same route as an older smaller one is cheaper to build than several new small pipelines. Plus, permits and rights-of-way of the old pipeline can be used without obtaining additional new pipeline routes. Increasing the diameter of a pipe increases the flow of natural gas. For example, Enbridge replaced a 26-inch-diameter shale gas line running from Pennsylvania into New England with a 42-inch diameter pipeline. While it is only 1.6 times in diameter larger, the new pipeline can carry many times as much natural gas as the older one. Further, the newer pipe has more flexibility—flows can be reversed, expanded, or optimized.

Conclusion

Clearly, the above figures during this past winter show that New England is on the edge of reliability problems. Because of good operations and probably some luck, the region managed to get through this winter’s cold snap, but it needs a better long-term strategy. The region is placing that strategy into the hands of renewable energy, but renewables did not save the day during this cold spell. The politicians and consumers in New England need to assess whether they want reliable energy or risk overreliance on the intermittency of the wind and sun.