San Francisco wants to become carbon neutral by 2045 and is looking at ways to ban natural gas in existing buildings. The city has already banned natural gas use in new buildings, which must be all electric or renewable. Currently, natural gas use in existing buildings generates about 38 percent of San Francisco’s greenhouse gas emissions. In residential buildings, the largest use of natural gas is for appliances: water heaters, furnaces, ovens, laundry dryers, etc. As the U.K. found out, electrifying homes is a monumental challenge. The “key barrier” to achieving an electric retrofit of existing residences is the financial burden. Electrifying existing residences could be accomplished by compelling all property owners by legal mandate to replace all gas appliances with electric at their expense, or partially or fully funding these costs by the city. Rebates and low interest loans could be used as tools to make mandated retrofits less financially burdensome to property owners.

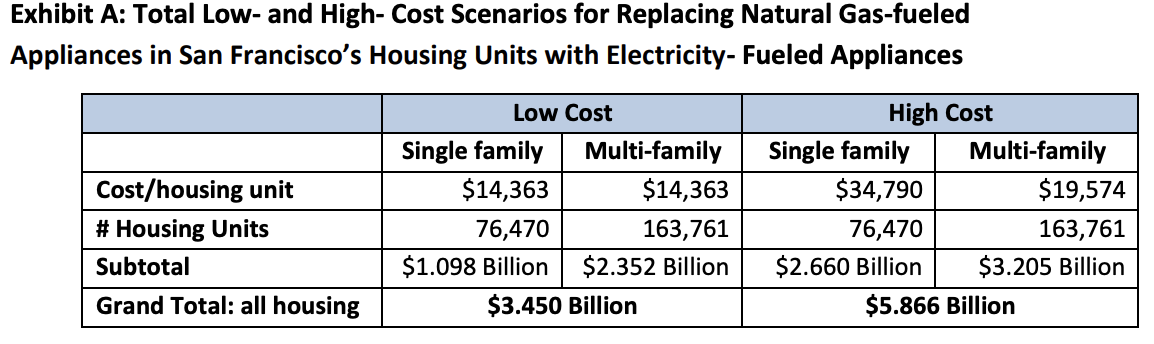

According to the report that the city initiated, the estimated cost of an electrical retrofit of appliances in residences ranges from a low of $14,363 per housing unit up to $19,574 for multi-family units and $34,790 for single-family homes. Costs include disposal of old appliances, purchase of new appliances, labor and electrical panel upgrades. In San Francisco, an estimated 61 percent of the total housing stock (240,231 housing units) use natural gas for some or all of the appliances. That total includes 76,470 single-family homes and 163,761 multi-family homes. Natural gas has been chosen because of its lower cost for consumers and its efficiency as a heating fuel. The cost to replace natural gas appliances with electric appliances is estimated at between $3.5 billion and $5.9 billion for the city.

The main issues for the residential electrification effort are 1) the cost; 2) who would shoulder the cost; and 3) how fast San Francisco wants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings. The city could implement requirements to make electric appliance retrofits mandatory on all residences at the time of a sale or when gas-fueled appliances have to be replaced at the end of their lifetime. Requiring retrofits on the natural replacement cycle could drop total costs to between $642 million and $2 billion. Another possibility is imposing a fee on natural gas buildings, which New York City does for larger buildings. The fee would be lifted once those buildings are converted from natural gas to electric. These approaches could take decades to achieve with gas appliances such as furnaces lasting 20 to 30 years. A way to speed up the effort is having the city fund a retrofitting program through issuing debt.

In addition to the cost of retrofitting, the unit cost of electricity is currently higher than the unit cost of natural gas, potentially placing an additional cost burden on property owners who retrofit. California’s electricity prices are the fourth highest in the nation and they have been escalating. Thus, the total annual energy cost tends to be greater for electric appliances than for gas appliances.

San Francisco could choose to fund a retrofit program, charging residential energy users a tax similar to the one commercial users pay, which could generate $11.5 million a year. Another possibility is rebates: Sacramento’s utility district gives a rebate of up to $13,750 for ratepayers to convert their homes from natural gas to electric. San Jose grant-funds rebates up to $6,000 for low-income and $4,500 for a limited number of others.

Conclusion

Residential buildings are responsible for 23 percent of San Francisco’s greenhouse gas emissions. To achieve carbon neutrality, the city has to decarbonize residential buildings and transition off of natural gas in favor of renewable energy. The City’s Board of Supervisors has already banned natural gas in new buildings last year, but new construction is the low-hanging fruit of electrification that dozens of cities across California have already implemented. The challenge is retrofitting existing buildings and the question is who will pay the huge price, and how the funds will be obtained. Ensuring equality among consumer groups and incomes will also be a challenge. City officials are engaging in ongoing conversations with affordable housing providers, labor leaders and others about how to achieve the city’s goal. One thing is certain: electrification will cost billions of dollars in San Francisco and someone will have to foot the bill.