The 18-member presidential commission, headed by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, is set today to vote on its revised plan for reining in Washington’s bloated budget deficits. The commission’s supporters say the plan offers a painful mixture of spending cuts and tax hikes, and is the only responsible path to fiscal sustainability.

The controversy has centered around proposed cuts to Social Security beneficiaries. But one very troubling recommendation that has escaped scrutiny is the proposed 15-cent per gallon hike in the federal gasoline tax. This would be another blow to Americans, especially the working poor and middle-class, and is a counterproductive way to balance the budget.

A Huge Increase in the Gas Tax

Currently the federal government slaps an 18.4-cent surcharge on every gallon of gasoline purchased in America. The proposed 15-cent hike would therefore constitute a whopping 82% increase in Uncle Sam’s tribute every time motorists fill up.

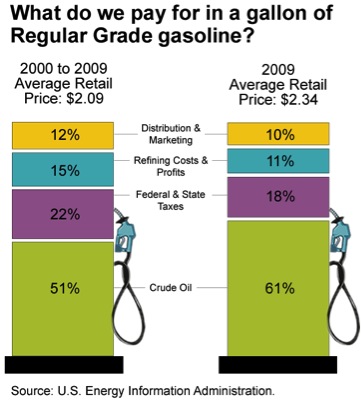

When we include the 23.7-cent per gallon average state tax on gasoline, we find that taxes constitute a large chunk of the total price at the pump:

As of the last week in November, retail gasoline prices averaged $2.91 across the country. Now it’s true, an additional 15-cent hike in the federal tax wouldn’t necessarily translate into a 15-cent rise in retail prices for consumers. The burden would in fact be shared between consumers and producers, the former seeing price hikes and the latter retaining less after-tax revenue per gallon sold.

However, the demand for gasoline—like cigarettes—is relatively inelastic, meaning that motorists will not significantly reduce their purchases, especially in the short run, because of a price hike. That suggests that motorists will bear the brunt of any hike in the gas tax. Inasmuch as fuel costs are a higher proportion of the household budget in poor and middle-class families—especially where one or both spouses drive to work—this proposed tax is just about the opposite of what candidate Barack Obama promised voters during the presidential campaign. It is a new tax that will directly impact the working poor and middle class, while hardly affecting the affluent.

To Balance the Budget, Cut Spending

The need for deficit reduction is real; federal spending is truly unsustainable. (The total unfunded obligations of federal “social insurance” programs was estimated at $46 trillion in present market value in 2009; see the last page of this Treasury report.)

Even so, it doesn’t follow that the country needs massive new hikes. They are unnecessary and actually economically harmful. The proper way to deal with ballooning deficits is for the government to cut spending, not extract yet another pound of flesh from the taxpayers.

Although it defies conventional Keynesian wisdom, even in the short run it makes sense to cut government spending. This returns desperately needed resources back into the private sector, where they can be put to their most productive uses. This recommendation is not mere conservative ideology, either: The European Central Bank (of all places) last summer summarized the case for “fiscal austerity” as a way of stimulating economies that are in the doldrums, listing several case studies of countries that accelerated out of recessions while lowering their deficits. (See pages 81-86 here.) The ECB bulletin specifically mentions that spending cuts—as opposed to tax hikes—were particularly effective.

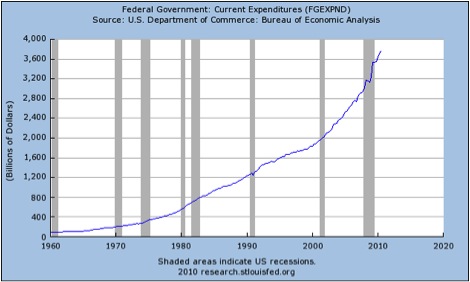

In the long-term as well, it is clear that the federal budget problem is one of out-of-control spending. A glance at the 50-year history in federal spending shows just how much it exploded in the Bush years, and then even more so in the brief time since President Obama took office:

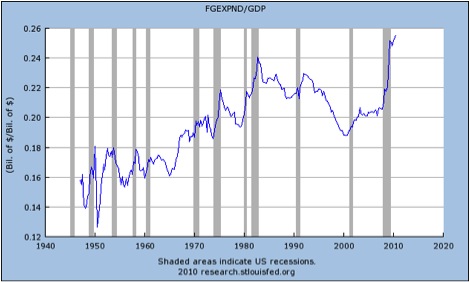

As for those who say that they merely wish to return income tax rates to the levels of the Clinton years, we can say the same thing about federal spending as a share of GDP:

As this last chart illustrates, currently federal spending constitutes about a quarter of the entire U.S. economy, a shocking level not seen since World War II. Federal spending was far lower, both in absolute terms but also as a share of GDP, during the 1990s.

Conclusion

Economies generally grow over time, both in absolute dollar terms but even adjusting for inflation. If the U.S. federal government would merely limit its rate of spending growth to less than the economy’s growth rate, while maintaining the same tax structure, then the string of budget deficits would eventually turn into a string of surpluses. The government’s budget is chock-full of absurdities that could be cut. Once the low-hanging fruit is gone, it’s true that there would be politically difficult choices in dealing with entitlement spending. Yet it’s hardly a consolation to working Americans to “save” Social Security (in part) by jacking up their gas taxes.