On Tuesday the Senate is expected to hold a vote on a bill that some Senators claim would raise an additional $20 billion over ten years by removing tax deductions for the five largest private oil companies.

Even among free market economists, the issue of tax deductions and credits is controversial, because it mixes the twin goals of tax simplification and tax reduction. However, what is crystal clear is that the popular arguments used to support the change in tax law don’t stand up to scrutiny. By effectively hiking taxes on oil producers, the government will not reduce oil prices—if anything it will raise them. Furthermore, the facts show that “Big Oil” is already “paying its fair share” in taxes. The sudden debate over tax policy seems more about a cash-strapped government going after deep pockets than about equity in the tax code.

Oil Profits and Oil Prices: Reversing Cause and Effect

Whenever discussing an effective tax hike on oil companies, President Obama and other leading Democrats constantly remind the public that these companies are earning very large profits while the average motorist groans because of the price at the pump. The implication is that the oil companies’ profits are the cause of high oil prices.

For example, in conjunction with introducing a windfall profits tax, Dennis Kucinich (D-OH) declared, “Consumers are being gouged at the gas pump,” and went on to say, “The only thing rising faster than the price of gasoline right now is the skyrocketing profits of the oil companies.”

Kucinich and others have things backward. High oil profits don’t cause high oil prices. On the contrary, high oil prices lead to high profits. Slapping a higher tax liability on major oil producers would certainly reduce their after-tax profits, but it wouldn’t reduce oil prices or what motorists pay at the pump. If anything, squeezing more tax revenue out of major oil companies would increase world oil prices, by reducing supply.

This principle shouldn’t be too hard for environmentalist opponents of oil companies to understand. Whcaat is their suggested tool to get companies to restrict the output of carbon-based energy? Why, to levy a tax on such operations.

President Obama and others who have supported the principle of a carbon tax (or cap-and-trade) can’t have it both ways: If they believe a tax on carbon will cause companies to shift out of carbon-intensive activities, then they should openly admit that hiking taxes directly on oil producers will, if anything, reduce the supply of oil and hence increase energy prices.

Equality Before the Law

Regardless of the other considerations, there is something unseemly when the government edits tax rules to raise $20 billion from five companies. For an analogy, if a local government said, “Motorists can turn right on red, unless their first name is Mortimer,” then this would be a travesty of the rule of law.

The situation is not far different when it comes to the proposed change in the tax code. Part of the changes would deny the (Section 199) Domestic Manufacturing Deduction that was originally put in place in 2004 to encourage American manufacturers to keep jobs in the United States, rather than outsourcing them. If policymakers think that the high deficit trumps these considerations, then by consistency they should eliminate the tax deduction altogether. It only further complicates the tax code by denying that particular tax deduction to five particular companies who had previously been qualified as manufacturers (because they produce oil and natural gas domestically).

In commenting on this episode, Freeman editor Sheldon Richman—hardly a friend of Big Business—wrote:

Discretion is dangerous. Politicians don’t need the traditional power of a central planner to impose economic schemes. All they need is the power to write differential tax policy. Virtually anything that can be done by regulatory decree can be also done by selective tax preferences….When government can shape economic behavior through the tax code, there surely is no free market. Tax neutrality is a chimera, but we should still object whenever the tax writers try to manipulate the economic process.

Putting Things in Perspective

In light of the bombastic rhetoric surrounding this issue, the average American probably believes that (a) the oil industry earns a much higher profit than other industries and (b) oil companies don’t pay much in taxes. Yet it turns out both claims are myths. The following charts are from the American Petroleum Institute (API), an industry trade group. They set the record straight and put things in perspective.

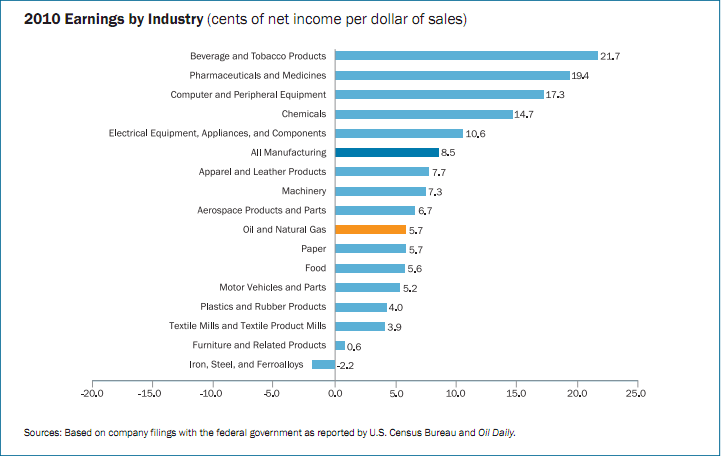

The first chart shows that oil and natural gas companies do not earn an unusually large amount per dollar of sales. In other words, their “markup” is actually much lower than that in many other industries:

The reason large oil companies can have such enormous total profits is that they have enormous revenues: Simply put, the majors such as Exxon and others sell a lot of product to consumers, and so their relatively tame profit-per-dollar adds up to a large total profit. Yet high profits aren’t a sign of bilking the public; on the contrary they are a sign that the company is serving its customers while keeping costs down.

The next chart shows that the major oil and natural gas companies had effective income tax rates in 2010 far higher than the average of the other members of the S&P 500:

The reader should interpret the above chart with care; the income taxes do not all necessarily go to the U.S. Treasury, because multinational corporations have worldwide operations and try to structure them to minimize their tax bite. Even so, the fact remains that oil and natural gas companies in 2010 owed 41.1 percent of their pre-tax income as tax to various governments. (As this Forbes article explains, oil and gas companies are actually at a disadvantage in this respect compared to most other multinationals, because other governments charge relatively high amounts on their activities.)

In any event, the U.S. federal government extracts billions from the major oil companies every year in taxes and other fees. They are huge, profitable companies that generally suffer from a poor reputation among the public. Of course the government has been exacting tribute from them, all along.

Conclusion

In terms of promoting economic growth, to design an efficient tax code from scratch would have low, flat rates and a very wide tax base (meaning few or no deductions or credits). The goal would be to raise the desired amount of revenue with as little distortion as possible to the allocation of resources across different sectors. The government shouldn’t use the tax code to pick winners and losers.

In the present context, policymakers are not starting from scratch, but are working with the tax code as it currently exists. The proposal to deny certain provisions of the tax code to a handful of rich companies is hardly an effort in tax simplification. Moreover, much of the rhetoric behind the proposal is based on myths. Hiking taxes on oil companies won’t reduce oil prices, and these companies already pay large amounts to the U.S. and other governments.