A major component of President-Elect Trump’s campaign consisted of promises to boost job and wage growth for average Americans. To do so, one obvious strategy—which Trump mentioned explicitly in speeches and which his campaign economic advisors included in their white paper—would be to remove federal obstacles from the energy sector. Indeed, we here at the Institute for Energy Research have recently released a blueprint for how a new Trump Administration could implement energy policies that achieve his stated goals.

Yet a recent Bloomberg article tries to throw cold water on such optimism. It claims that it will be difficult for revised energy policies to create “millions of jobs”—as Trump has recently claimed—because the labor market is just too tight for that. Yet as we’ll see, there is nothing farfetched about the claims. The IER study authored by Joseph Mason—which the Trump team used as part of its own projections—took into account the state of the labor market. Its estimates included “indirect” effects, and most important the Mason study acknowledged the state of the labor market in its projections.

The striking fact is that the “headline” unemployment rate of 4.6 percent masks a large drop in the fraction of the population that is actually working, with the lowest level since the mid-1980s. Some of this trend is the natural outcome of an aging population, but much of it (I would argue) is due to the misguided policies of the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations.

Bloomberg’s Skepticism

To give a flavor of the Bloomberg article’s skepticism regarding Trump’s promises, here are the opening two paragraphs:

President-elect Donald Trump promises that his sweeping changes to energy policy will create “many millions” of American jobs. Finding all those workers may be the challenge.

World markets are flush with coal and oil, keeping prices subdued and making it difficult for producers to profit from new investments. At the same time, the U.S. labor supply is thinning, meaning that adding millions of jobs in the energy industry alone is a tall order. The entire sector now employs 628,700 people in the U.S., about half of the peak in 1981, according to Labor Department records.

The rest of the Bloomberg piece is more nuanced, citing reasons that perhaps Trump’s claims aren’t so farfetched after all. In the rest of my post I’ll explain why the Trump team’s numbers are plausible.

No Incentive to Produce More Domestic Energy?

First, it is odd that the Bloomberg article argues that world coal and oil prices would keep producers from expanding US output. Producers have made their output decisions based on world prices and existing regulations. If Bloomberg’s pessimism were correct, then repealing the so-called “Clean Power Plan” from the EPA would have no impact, right? But of course if the Trump Administration moves to repeal it, you can bet environmental groups will be outraged. In any event, the Energy Information Agency’s own analysis projects that the “Clean Power Plan” will reduce coal’s share of electricity output from about 38 percent in 2014 down to 25 percent by 2030, while US coal production itself drops more than 30 percent by 2025 (compared to the Annual Energy Outlook 2015 baseline scenario). So the point is, whatever coal and oil prices are, getting rid of federal roadblocks will increase production relative to what it otherwise would have been.

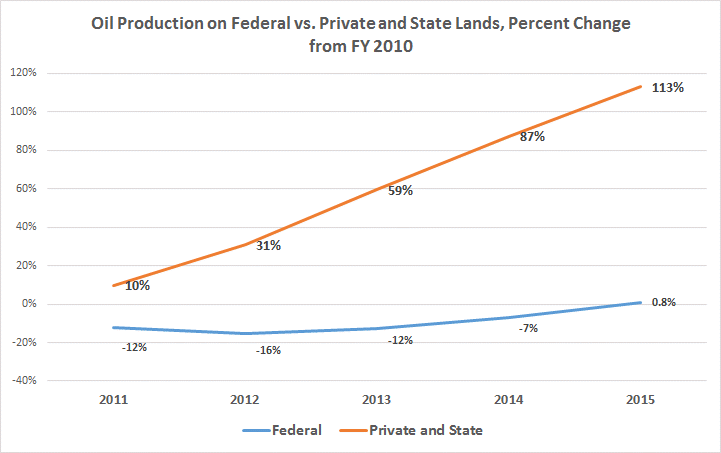

Turning from coal to crude oil and natural gas, there has been a huge difference in development of resources on federal vs. state or private lands under the Obama Administration. (See charts below.) So clearly, energy policy from Washington DC matters a lot.

Source: CRS, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42432.pdf

Source: CRS, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42432.pdf

Pitfalls in “Job Creation” Studies

In general, I share the Bloomberg article’s skepticism regarding large projections of “job growth” emanating from proposed government policies. Often a study uses some type of statistical technique to gauge job growth G in a certain region resulting from a small dose of policy X, and then extrapolates to conclude that a policy of 100X would create 100G of new jobs in the overall economy.

One of the big problems with this sort of naïve extrapolation is that it ignores the possibility that expanding employment in one sector might suck workers out of other sectors, so that the net growth in total jobs is much less than the projections indicate.

Think of it this way: No matter what policy the government adopts, it can’t possibly “create jobs” that exceed the number of total workers. So it’s obvious that simply slapping on an empirically estimated “multiplier” to some policy change is going to break down, when the numbers get big enough.

Furthermore, an even more fundamental problem with many of the “job creation” estimates is that they forget what the whole point of employment is: to transform resources into goods and services that consumers actually want. The mere fact of “creating jobs” by itself is arguably a bad thing if the new “jobs” don’t produce real value. For example, if the government banned the use of backhoes and instead people had to dig holes with shovels, then that might “create jobs” in the construction sector. But it would obviously be a cure worse than the disease, as labor productivity would plummet along with overall standards of living.

IER’s Study on Solid Ground

Fortunately, the Mason study avoids these fallacies. By studying the effects of getting government out of the way of private energy development, we can be assured that workers in the “newly created jobs” are being channeled into their most valuable niches. Thus, they are not filling a job for its own sake, but because employers anticipate that workers in these newly created slots will produce more value for consumers.

Furthermore—and of relevance to the Bloomberg skepticism—the Mason study acknowledges that there are only a finite number of workers in the country. Here’s what the study says: “Over 552 thousand jobs could be created for the next 7 years with almost 2.7 million jobs after that, aiding economic recovery for workers facing historically high un- and under-employment rates” (p. 2).

Headline Unemployment Rate Misleading

The hot news is that the headline unemployment rate of 4.6 percent is the lowest since August 2007. So does that mean the labor market is fixed and a new Trump Administration shouldn’t worry about “good jobs”?

Not at all. The headline number simply reflects the percentage of people who have no work but are actively seeking it. The official number doesn’t reflect the people who are in miserable jobs, or who have dropped out of the labor force altogether because they have given up hope.

To get a fuller picture of the situation facing American workers, consider the following chart of civilian employment-population ratio:

As the chart shows, in the fallout from the Great Recession the fraction of the US civilian population actually working is at the lowest level since the mid-1980s. Yes, there are underlying demographic shifts occurring—in particular, an aging population—but the chart makes it clear that collapse occurred quite suddenly, as a result of the recession.

Conclusion

In the long run, so long as wages are allowed to reach market-clearing levels (which isn’t the case when we consider minimum wage laws), anybody who wants to find a job can get one. The real benefit of wise government policies, in this respect, is to make better-paying jobs, consistent with a higher standard of living. Americans are richer today than Americans in 1916 were, and it’s not because we work more.

However, these long-run considerations are not the only ones relevant at the moment. There have been major structural blows to the US labor market, starting with the dot-com recession but especially during the Great Recession. There are many reasons for the decline in the fraction of Americans who are employed, but unleashing the domestic energy sector will surely be a move in the right direction. It’s impossible to precisely estimate the effects of a set of policies on “total job creation,” but President-Elect Trump’s statements are plausible.