It is not enough that Congress and the Environmental Protection Agency have legislation and rules to reduce flaring and methane leaks, but now the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is adding its own rules to the list. BLM’s proposal would tighten limits on gas flaring on federal land and require energy companies to better detect methane leaks. The rule would impose monthly limits on flaring and charge fees for flaring that exceeds those limits. The EPA rule that President Biden recently announced in Egypt covers methane emissions from existing oil and gas wells nationwide, including smaller drilling sites that will be required to find and plug methane leaks. Besides the EPA rule, the so-called Inflation Reduction Act imposes a fee on energy producers that exceed a certain level of methane emissions. That fee is set to rise from $900 per metric ton in 2024 to $1,500 per metric ton of methane emissions by 2026. The BLM will accept comments on the proposed rule through early February, with a final rule expected next year.

Oil drillers usually flare (burn-off) natural gas produced as a byproduct to oil when they lack pipelines to move it to market or when prices are too low to make transporting it worthwhile. Other reasons to flare natural gas include safety concerns and connectivity issues. However, it is always in the best interest of an oil and gas producer to capture and sell the supplemental natural gas on the marketplace when at all possible, and that is what oil companies do. A new study of the flaring of natural gas from wells in the United States by consultant Rystad Energy for the Environmental Defense Fund determined that infrastructure capacity limits are the greatest use of flaring gas that cannot be captured, but the Biden Administration has been proposing to make it even more difficult to build pipelines.

BLM estimates that its new rules on methane will cost oil and gas companies around $122 million per year to implement and they will receive $55 million per year in sales of recovered gas. That gas will also increase royalty revenues paid to the U.S. government by $39 million per year.

Permitting Reform Needed to Handle the Problem

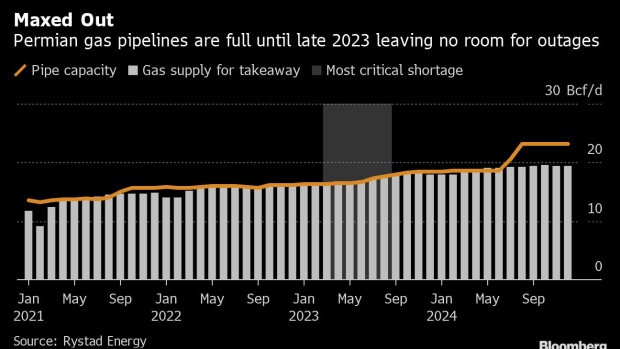

Operators in America’s biggest shale oil basin, the Permian, are expected to significantly increase the amount of natural gas they flare because of a lack of pipeline capacity to ship it. Natural gas pipelines in the Permian are effectively maxed out until the latter half of next year when several pipeline expansions come online to ease the shortage. Producers that have not obtained space on existing pipelines must either reduce gas production halting more valuable oil production or continue to pump oil and burn off the excess gas. Doing the latter would threaten to undo much of the progress achieved in the last few years to address the industry’s flaring situation.

The Permian basin’s gas production has increased by more than 30 percent since the pandemic compared to an increase in oil output of 12 percent, creating the issue. Gas takeaway capacity is expected to be tight for most of next year and probably into 2024 when some major pipelines come on-line. With pipelines effectively full, it is likely that operators may already be increasing flaring. If unscheduled outages should occur, the gas has nowhere to go.

Pipeline companies like Energy Transfer LP or Kinder Morgan Inc. typically prefer to build or expand pipelines when they are confident there will be enough oil or gas to fill them. If they build a pipeline too early, there is a risk of not securing enough flows to repay the high upfront cost. But building them too late results in transportation shortages increasing the need to flare. Further, it is easier to get flaring permits from the Texas Railroad Commission than pipeline permits from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in Washington, D.C.

Biden’s Pledge to Cut Methane Emissions Does Little for Temperature Change

At the U.N. Conference of the Parties last year in Scotland (COP26), the United States pledged to cut methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030 from 2020 levels. But, few realize that large increases in the concentrations of greenhouse gases cause very small changes in the heat balance of the atmosphere. Doubling the concentration of methane – a 100 percent increase, which would take about 200 years at the current growth rates – would reduce the heat flow by only 0.3 percent, leading to an average global temperature change of only 0.2 °C, which is less than one-quarter of the change in temperature observed over the past 150 years. That is, even if regulations on U.S. methane emissions could completely stop the increase of atmospheric methane, they would likely only lower the average global temperature in the year 2222 by about 0.2 °C–a trivial amount.

Given that consumption of fossil fuels is likely to increase over the next few decades as developing countries pull themselves out of poverty, restrictions on U.S. oil and gas production will simply shift production to autocratic nations such as Russia, which have much higher methane-emissions rates than U.S. producers do. Also, if the Biden administration is successful in promulgating regulations on oil and gas producers, it will expand those efforts into ranching and agriculture, which emit about the same amount of methane as energy production. This potential vast expansion of federal control into essential economic functions is why some believe actions targeting energy production and use are a convenient excuse for broadening government control.

Conclusion

President Biden is using Congress and every agency in the government to regulate methane flaring, leaks and emissions, even taxing methane emissions as in the Inflation Reduction Act, which he signed into law this summer. This is consistent with his promise to “end fossil fuels.” The latest Biden administration attack on methane is a new proposed rule from BLM for methane flared or leaked on federal lands. It is important for Americans to realize that these rules increase the cost of oil and natural gas production, which are passed onto the products Americans use, that there is limited takeaway capacity to offer the natural gas for sale, and that the temperature change from the reduced methane emissions is trivial—just 0.2 °C over 200 years.