Some forecasters believe $100 a barrel oil is on the horizon in 6 to 12 months. President Biden wants to electrify transportation and he may get his wish, as $100 a barrel oil may push buyers toward electric vehicles sooner than expected, adding to the momentum created by the bans that some states and countries have suggested on gasoline and diesel vehicle sales. California and the United Kingdom, for example, will ban sales petroleum-fueled vehicles beginning in 2035 and 2030, respectively. The world, however, has not seen $100 a barrel oil since mid-2014 when that oil price pushed gasoline prices toward $4 a gallon in the U.S.

Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling at shale basins in the United States brought a renaissance to oil drilling, and oil prices plunged to about $30 a barrel in January 2016. Since OPEC found it could not control the market with the U.S. oil shale boom, Saudi Arabia reached out to Russia and other non-OPEC producers to form the OPEC+ group to take back control of global oil markets. That didn’t work until the coronavirus pandemic hit reducing oil demand and oil production. Now Joe Biden has become president and is doing all he can to put a damper on U.S. oil production giving OPEC+ free rein to control global prices.

OPEC and U.S. Shale Oil

OPEC+ decided to keep a tight limit on oil production next month, sending prices soaring in a market that had been expecting additional supply. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has consistently pushed to tighten the market. The cartel had been debating whether to restore as much as 1.5 million barrels a day of output. But OPEC members agreed to hold steady at current levels—with the exception of modest increases granted to Russia and Kazakhstan. Russia and Kazakhstan are allowed to boost output by 130,000 and 20,000 barrels a day in April, respectively, due to continued seasonal consumption patterns following an extremely cold winter. And, Saudi Arabia made its additional 1 million barrel-a-day production cut open-ended, giving no date for phasing out the voluntary reduction. Overall, OPEC is producing nearly 2 million fewer barrels of oil daily than at this time last year.

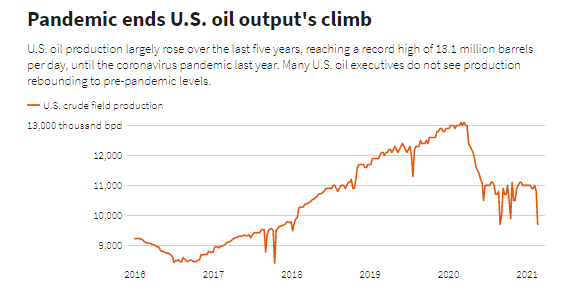

In the past, rising oil prices have enticed shale companies to ramp up production even after they promised prudence, and $60 oil would have once prompted companies to rush drilling rigs and hydraulic fracking fleets back to work. That is not happening now. Private companies are likely to increase oilfield activity, but not enough to meaningfully boost U.S. output, as companies prioritize shareholder returns after a devastating year when oil prices went negative during a unique confluence of COVID-induced demand reduction and overproduction. The severe drop in activity in the United States and the pressure from the investment community to maintain discipline instead of growth means that shale oil will not get back to where it was in the United States, at least not for a while.

In many cases, operators must commit to producing barrels before they know what the price will be. In this case, OPEC can let prices rise and add barrels at its discretion, which provides OPEC a great deal of control and flexibility over oil prices. OPEC can add more barrels on fairly short notice if it believes the market is overheating. OPEC+ has more than 7 million barrels of daily oil output in reserve—about 7 percent of global oil demand. This positions them to boost production much more easily than shale oil players for the first time in years.

Brent oil, a global oil price measure, has already rallied about 30 percent this year to almost $68 a barrel. Throughout the first quarter, OPEC+ kept production below demand in order to drain the oil glut that built up during the worst of the COVID-19 lockdowns. Without additional supply, the cartel believes that the deficit will widen significantly in April, raising oil prices to $70 or $75 a barrel. OPEC+ will meet again on April 1 to discuss production levels for May.

Gasoline prices

Gasoline prices have already reached $4 per gallon in California and are close to $3 per gallon nationally for regular. Gasoline prices topped $3 a gallon on March 14 in nine states and the District of Columbia, part of a steady national rise since November that some analysts expect to hit the $4 mark soon.

California’s higher gasoline prices are in part due to higher state and local taxes and in part to the requirement to use cleaner-burning fuel that was adopted in 1996 and which costs more to make. There are also environmental fees. The state’s cap-and-trade program on greenhouse gases added 12 cents a gallon in 2019 and the “low carbon fuel standard” pushed the price up by about 8 cents in that year. There is also a 2-cent fee to clean up old gas station sites.

Conclusion

In April 2018, former President Donald Trump reacted quickly with a barrage of tweets to the threat of rising gasoline prices, resulting in OPEC+ changing its approach to oil production. The reaction of the Biden administration is vastly different as it moves further toward implementing green policies. Higher prices for fossil fuels help the Biden Administration’s goals. Biden reenrolled the United States in the Paris Agreement and committed the nation to the goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. One of Mr. Biden’s first moves in office was to revoke permits for the Keystone XL Pipeline, which would have carried 800,000 barrels of oil per day from Canada to refineries in the Texas Gulf Coast region. He also issued a moratorium on new oil and gas drilling on federal lands. These are strong market signs that the priority of domestically-produced energy that led in 2019 to energy independence (producing more energy than we consumed) is no longer important to the U.S. government, and is being responded to by the markets and oil producers throughout the world.

Higher oil prices to Biden means a quicker exit from petroleum in the transportation sector and a quicker transition to electric vehicles. As Americans go back to work, they will need to lower their commuting costs in any way possible as higher transportation costs and impending inflation become the norm.