- China and India – both considered “developing countries” by the IPCC – are burning record amounts of coal and using more kinds of energy to keep energy prices affordable and increase the standard of living for their people.

- Wind and solar energy in China and India are complements, not substitutes, to their massive growth in energy, particularly in fossil fuels.

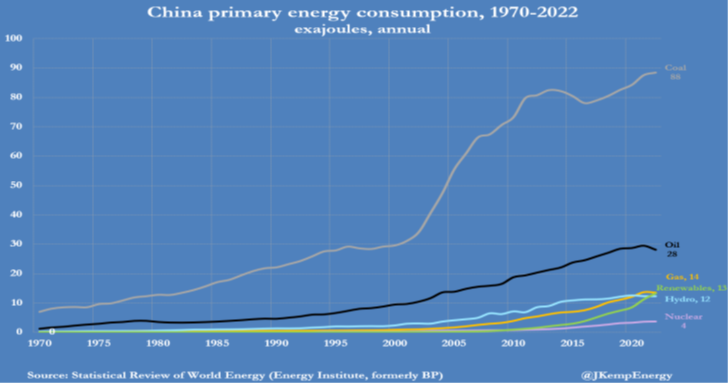

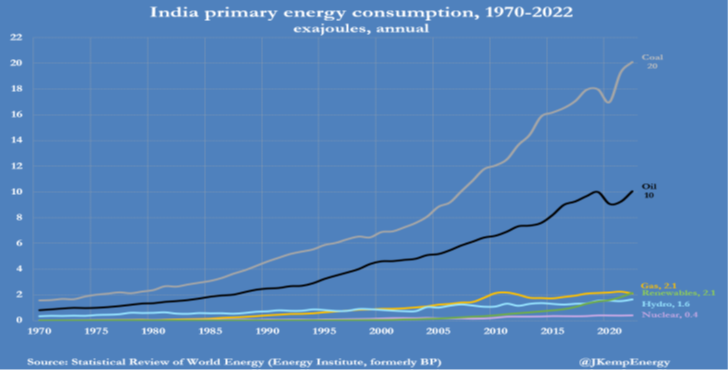

- Fossil fuels provided 82 percent and 88 percent of China and India’s energy, respectively, in 2022.

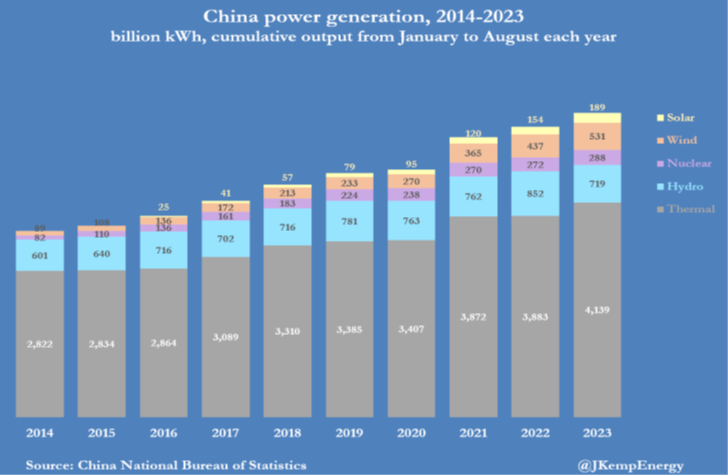

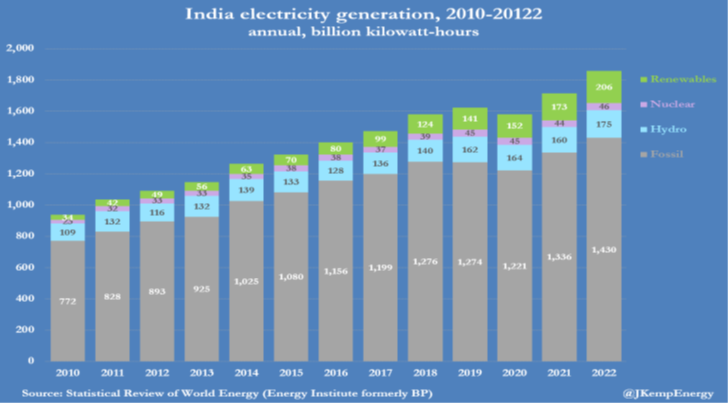

Both China and India are experiencing rapid growth in energy use for services such as air conditioning, heating, cooking, lighting, power and transport as they attempt to raise living standards closer to those in the advanced economies. Both countries depend heavily on coal for their electric power generation. In China, domestic coal production is at a 6 month high; in India, declining coal inventories are requiring more coal to be imported. Growing demand for energy services is so vast that both fossil fuels and renewable energy are increasing and acting as complements rather than substitutes. Further, both China and India are likely to consume far more electricity in the next few decades as their populations seek to reach the same living standards as North America and Europe. Unlike developed countries, both China and India want to ensure energy remains affordable and reliable for their people and industries. China and India are increasing their use of indigenous coal even as they import more oil and gas, build and use more nuclear power, and invest in renewable generation from wind, solar and hydro.

In 2022, the populations of China (1.43 billion) and India (1.42 billion) were each similar to the total for countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (1.38 billion). Total primary energy consumption, however, in China (159 exajoules) and India (36 exajoules) was far lower than in the OECD (234 exajoules). (One exajoule is roughly energy equivalent to 174 million barrels of oil.) In China, consumption per person in 2022 was 66 percent of the energy their counterparts in the OECD demanded and in India, the figure was just 15 percent. Both countries, however, and particularly China export a high proportion of their energy-intensive manufactured output to the OECD, which makes the dichotomy on a per person basis even larger. The off-shoring of manufacturing by countries of the OECD simply transfers the energy consumption there.

China’s and India’s Electric Generation

In 2022, fossil fuels accounted for 82 percent of primary energy consumption in China and 88 percent in India, with fossil fuels providing 70 percent of electricity generation in China and 77 percent in India. While the share of fossil fuels used in electricity generation remains high, renewable capacity has increased in both countries. Since 2018, China’s solar generation capacity grew 26 percent per year and wind generation capacity by 18 percent per year, while thermal capacity grew by 4 percent per year. In India, solar generation capacity grew by 25 percent per year, wind grew by 5 percent per year, and coal grew by 1 percent a year. Of course, renewable capacity growth in both countries occurred from low amounts resulting in the large percent increases, while the opposite is true for thermal capacity. Despite policymakers from OECD countries wanting China and India to speed up their transition from fossil fuels to zero-emission alternatives, the reality is that both governments have prioritized increasing access to energy services and ensuring energy remains affordable and reliable, which follows the historical pattern of the OECD nations. China and India also welcome manufacturing, which has been transferred from OECD countries, and its associated jobs.

The global problem of transitioning from affordable and reliable fossil fuels to non-zero carbon alternatives will only get worse as sub-Saharan Africa continues growing in population and energy needs. Its population increased to 1.20 billion in 2022 and is forecast to rise to 2.17 billion by 2050 and 3.57 billion by 2100. The region’s urbanization, industrialization and energy consumption per person now is lower than China and India, but has commensurately greater potential to increase in the future.

China’s Coal Consumption and Production

In 2022, China’s coal consumption grew by 4.6 percent to a new all-time high of 4.5 billion metric tons–nearly 9 times higher than the United States, and it is expected to be higher yet this year.

China’s September coal output increased 0.4 percent from August to the highest level since March, due to rising power demand as economic activity picked up. In September, coal production was 392.98 million metric tons (13.1 million metric tons per day), compared with an average of 12.71 million metric tons per day so far this year. For comparison, the United States consumed 513 million short tons of coal in all of 2022. Economic activity picked up in China after the summer due to several economic stabilization measures.

China’s coal-fired electricity generation increased by 2.3 percent year-on-year in September, while power demand increased by 9.9 percent. Coal output over the first nine months of 2023 was 3.44 billion metric tons, up 3 percent compared with the same period last year, and putting China on track for another year of record coal production. In 2022, China produced 4.496 billion metric tons of coal—a record. Production is expected to continue to increase in the fourth quarter as mines have resumed normal operations following accidents, and state-owned miners are increasing production to ensure sufficient supply during the winter.

The production of coke used in steelmaking increased 3.6 percent in September to 41.44 million metric tons, with year-to-date output reaching 368.31 million metric tons, up 2.6 percent.

India Imports More Coal

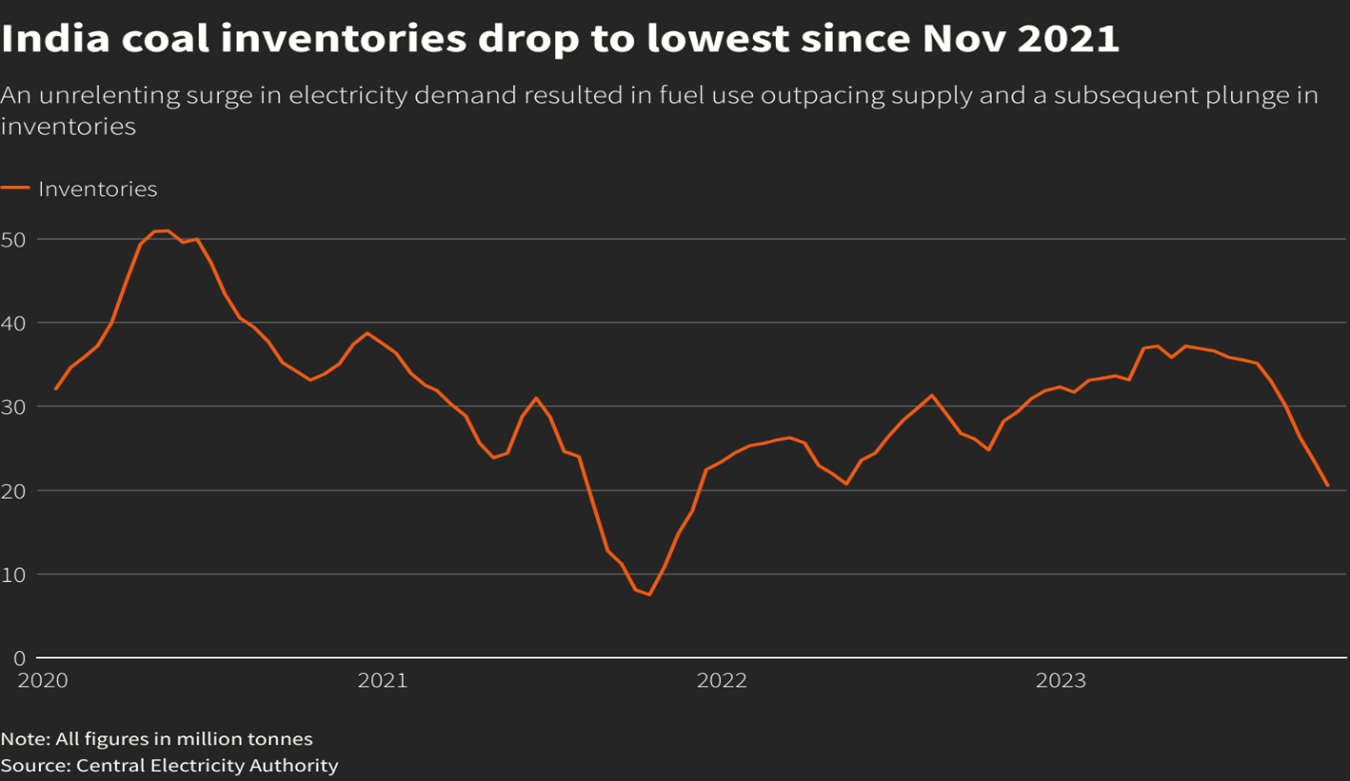

As electricity demand increased in October, India had to increase its coal imports because fuel use outpaced domestic supply. Coal inventories held by power plants fell by 12.6 percent to 20.58 million metric tons in the sharpest decline since the second half of September 2021. Stocks fell to their lowest level since November 2021 despite state-run Coal India, the dominant domestic supplier, increasing supplies to power plants by 6 percent year on year to 23.5 million metric tons. India-bound shipments of thermal coal are expected to increase to 19.35 million metric tons in October, the highest level since June 2022.

India’s coal-fired power generation increased 33 percent year on year in October – much faster than the 21.6 percent increase in September. Unusually dry weather, decreasing hydropower output, a decline in renewable generation, and an increase in economic activity increased coal consumption in October. Power demand increased 20.4 percent, while hydropower output declined by 26.8 percent. The share of generation from renewable sources (wind and solar power) fell to 10.1 percent in the first half of October from 12.1 percent in September. Natural gas-fired generation also increased almost three-fold in the first half of October to 1,993 million kilowatt-hours, up from 700 million kilowatt-hours a year earlier.

Conclusion

To the disappointment of politicians in the developed world, the developing world is not transitioning from fossil fuels to non-zero carbon energy. Rather, the developing world is using renewable energy as a complement to traditional generating technologies, not as a substitute. Using it as a complement avoids the need for costly batteries to back-up intermittent and weather-driven wind and solar power. The developing countries want to reach the living standard of North America and Europe and see fossil fuels as the most affordable and reliable way to get there, despite what western politicians say about it.