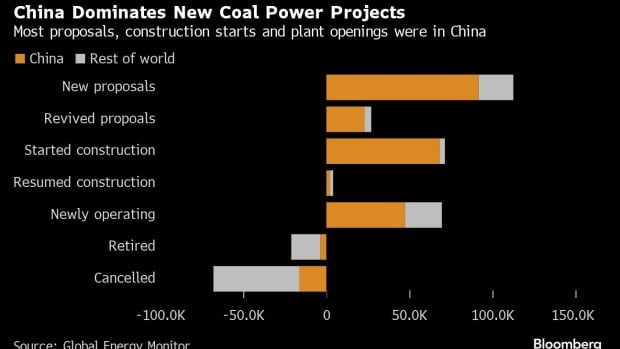

China was responsible for 96 percent of global coal power capacity construction in 2023 and is the biggest coal builder in the world. The country also accounted for 68 percent of new coal generation capacity that came online last year and 81 percent of newly planned coal generation projects. According to China, energy security comes before energy transition. Government officials in China claim that most of the new coal capacity will operate as backup for wind and solar power, which cannot generate electricity round the clock, unlike coal power plants.

This year, India will start operating new coal-fired power plants with a combined capacity of 13.9 gigawatts–the highest annual increase in at least six years. Further, private Indian firms have expressed interest in building at least 10 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity over a decade, ending a six-year drought in significant private involvement in the sector. India’s government cited energy security concerns amid surging power demand and low per-capita emissions to defend its dependence on coal. In 2023, India’s power generation increased by 11.3 percent–the fastest pace in at least five years. Both countries are relying on coal despite meetings held each year by the U.N. Conference of the Parties to phase out coal use, and both use more coal than the United States.

China

China has the highest installed capacity of coal power plants in the world. As of July 2023, it operated coal plants with a combined capacity of 1,108.91 gigawatts, which was more than five times the operational capacity of coal plants in the United States with the third most capacity. During the first half of 2023, China approved more than 50 gigawatts of new coal power–more than it did in all of 2021. Coal power generates 61 percent of China’s electricity and makes up about 70 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions in China. China’s emissions are the largest in the world and over twice as high as those in the United States.

Coal production in China hit a record last year, at 4.66 billion metric tons–2.9 percent higher than production in 2022. Higher demand after the COVID restrictions were lifted and higher domestic coal prices led to record-high coal imports into China, which increased by 61.8 percent to 474.42 million metric tons in 2023. The International Energy Agency expects China’s coal demand to drop this year and plateau through 2026.

In the latter part of 2023, China ramped up coal and natural gas production, imports, and consumption as its electricity demand jumped in the second half and is expected to hit a record-high winter peak demand. China like other areas of the world has suffered from low hydroelectric power output. It has invested heavily in renewable energy accounting for $546 billion, or nearly half, of the $1.1 trillion that flowed into the sector in 2022. But, while it has the world’s largest solar and wind capacity, it recognizes the need for reliable and affordable energy that coal provides.

India

According to India’s power ministry, in the next 18 months, about 19.6 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity is likely to be commissioned that includes the 13.9 gigawatts expected to be commissioned this year. The 2024 capacity increase is more than four times the annual average in the last five years. India added 4 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity in 2023–the most in a year since 2019. In 2023, coal-fired generation rose 14.7 percent, outpacing renewable energy generation growth for the first time since at least 2019, which increased 12.2 percent in 2023.

India did not achieve its goal of adding 175 gigawatts of renewable power capacity by 2022. The planned coal-fired capacity increase in 2024 will exceed its 2023 renewables increase of 13 gigawatts. Since wind and solar power have much lower capacity factors than coal, the increase in output from the wind and solar units will be much less than coal despite similar capacity additions. India’s Ministry of Power wants to add at least 53.6 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity over the eight years ending March 2032, in addition to the 26.4 gigawatts currently being constructed. Coal-fired capacity accounts for over 50 percent of India’s installed capacity of 428.3 gigawatts and a much higher share of its generation (75 percent). Coal-fired power plants in India currently account for about 235 gigawatts, renewables account for 134 gigawatts and hydro accounts for 47 gigawatts.

India’s government is trying to attract private investment to boost its coal-fired capacity by 80 gigawatts by 2032. Adani Power, JSW Group and Essar Power are among the companies that have told India’s power ministry they are interested in expanding old plants or developing stalled projects facing financial stress. Among the new proposals, Adani Power plans to add 4.8 gigawatts and JSW Group 1 gigawatt. Essar Power plans 1.6 gigawatts of new domestic coal-based power generation in Gujarat state by 2029, and Vedanta will add 1.9 gigawatts of capacity.

In the five years to March 2018, private sector investments drove 56 gigawatts— over 60 percent of new coal-fired power, but that decreased to 1.5 gigawatts (5 percent of additions) in the next five years as projects faced financial stress, shifting the investment burden onto state and federal governments. Currently, 24 private sector projects totaling over 23 gigawatts (over 10 percent) of current Indian coal-fired capacity are on hold or unlikely to be commissioned due to financial stress. Higher coal dependence in the last three years due to slower renewable installations, heavy power demand, and new emergency laws enabling higher tariffs have made coal-fired power attractive again, increasing profits and pushing shares of generators to record highs.

India has ramped up its coal production after coal inventories fell to critically low levels in October due to a weak monsoon curtailing hydro generation, which forced the country to rely heavily on coal-fired generation in the summer and autumn of 2023. Inventories recovered strongly in November, December, and January, with record volumes of coal dug and dispatched by rail to generators. Generators are currently storing 38 million metric tons of coal on site, up from 33 million metric tons at the same point in 2023 and 25 million metric tons in 2022. Inventories are sufficient to cover almost 14 days of generators’ minimum requirements up from 12 days in 2023 and nine days in 2022. The country’s mines raised production by 106 million metric tons (12 percent) and the volume delivered to generators increased by 50 million tons (7 percent) in 2023 compared with 2022. As a result, coal-fired power plants were able to generate an extra 11 billion kilowatt-hours (6 percent) in November to December compared with the same period in 2022.

Conclusion

Despite the push by Western countries at COP 28 to phase out coal, China and India are still building coal-fired plants that will last 40 to 50 years for energy security reasons. Despite adding renewable capacity, they realize that wind and solar cannot operate 24/7 and must have back-up. Rather than invest in costly batteries to store excess power from wind and solar units, they are building coal-fired plants that add much more generating capability and flexibility to their power grids. It is also inexpensive power that fuels their economies and has made China a powerhouse in steel and cement production, silicon and solar panel manufacture, and the processing of critical minerals needed for renewable technologies, electric vehicles and weapon production. Western countries, including the United States, would do well to learn from the example they set for reliable and affordable energy.