A team led by University of Leeds researcher Jefim Vogel has published a new study, “Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use,” in Global Environmental Change. According to the study, to save the planet from climate change, Americans must cut their energy use by more than 90 percent and families of four would need to live in housing no larger than 640 square feet. Public transportation would account for most travel and travel would be limited to between 3,000 to 10,000 miles per person annually.

The team argues that human needs are sufficiently satisfied when each person has access to the energy equivalent of 7,500 kilowatt-hours of electricity per capita, which is the amount of energy that the average Bolivian uses. Currently, Americans use about 80,000 kilowatt-hours annually per capita. With respect to transportation, the average person would be limited to using the energy equivalent of 16 to 40 gallons of gasoline per year and take one short- to medium-haul airplane trip every three years or so.

The average food consumption per capita would need to fall to 2,100 calories per day—about 900 calories short of the daily global average food supply of just under 3,000 calories per person. Each individual is allocated a new clothing allowance of nine pounds per year, and clothes may be washed 20 times annually. The study allows everyone over the age of 10 to have a mobile phone and each household can share a laptop computer.

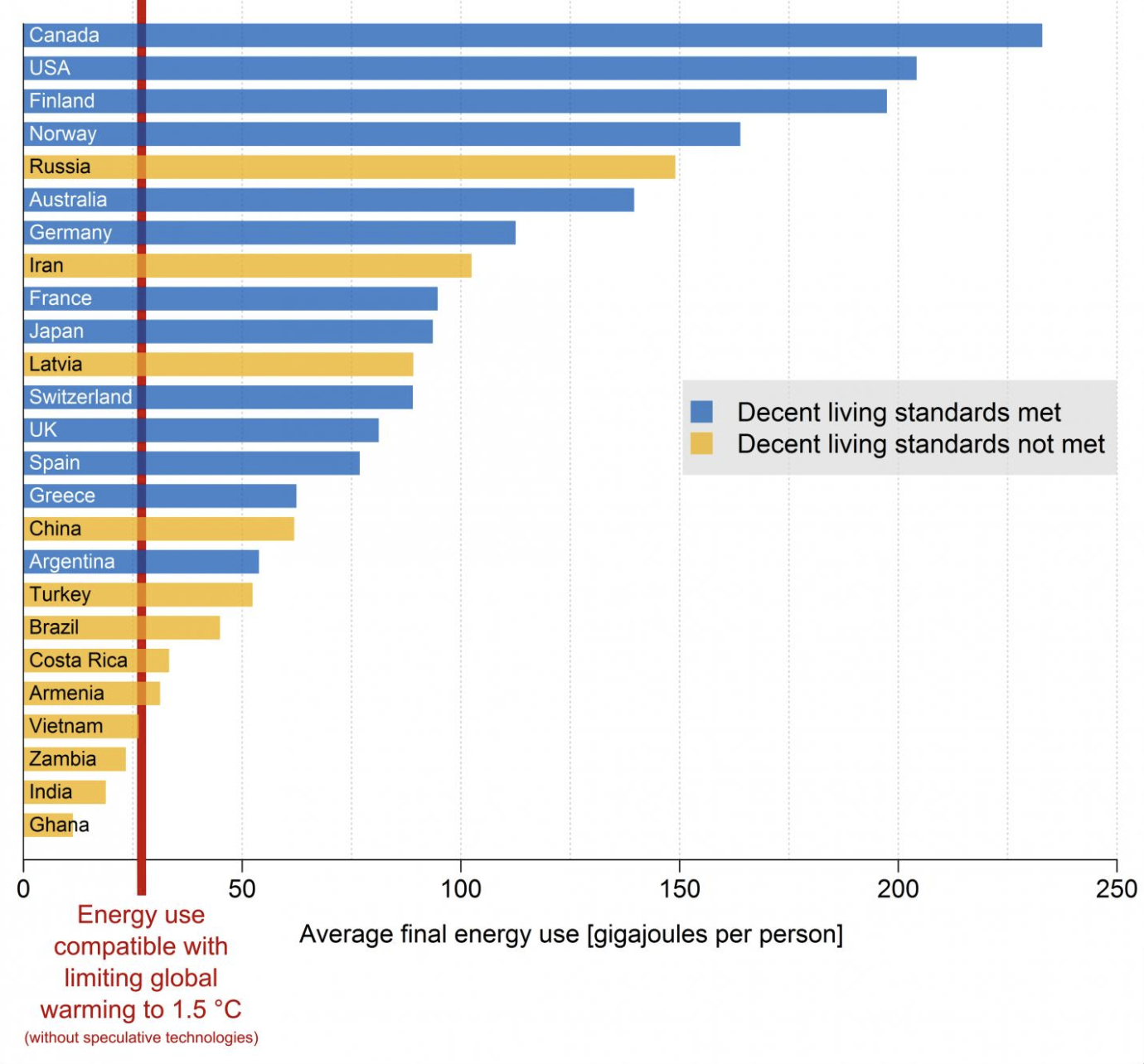

In order to stay below the 1.5°C temperature increase threshold that the Paris climate agreement considers necessary, earlier research calculated that the average person should be limited to using 18 gigajoules per year (equivalent to 136 gallons of gasoline or 5,000 kilowatt-hours) of total energy. The team at the University of Leeds allocated a cap of 27 gigajoules (equivalent to 204 gallons of gasoline or 7,500 kilowatt-hours) per capita annually, which no country in the world with decent living standards has met nor do they come close. (See figure below.) By way of comparison, Algeria’s consumption was 2 times as much per capita in 2019.

When the team set their 27-gigajoule per capita threshold, they ruled out “speculative” technological progress. However, if transitioning to no-carbon energy sources with nuclear, wind, and solar power could be achieved, then going on the strict energy diet the study specified would be unnecessary. But, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, in 2020, the fossil fuel energy sources supplied 83.1 percent of the world’s consumption. Nuclear power, hydroelectricity, and non-hydro renewable energy only supplied 16.9 percent. That’s a long way to go in not too many years to reach a net zero carbon future.

Countries Take New Action against Climate Change

Recently, the European Union unveiled a new plan to control carbon dioxide emissions, China rolled out an emissions-trading system and the United Kingdom released a plan to reduce emissions tied to transportation. Called “Fit for 55,” the European Union’s program is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by at least 55 percent from 1990 levels by 2030. The European Union plans to ban sales of new internal-combustion cars by 2035 and subject aviation to the EU’s emissions-trading system. Another proposal requires vast expenditures to increase energy efficiency. There is a renewable-energy directive, and an update to the regulation on land use, forestry and agriculture that requires, among many other things, planting three billion trees by 2030. The plan also includes a proposal for a carbon tariff, which will put a carbon price on imports of a targeted selection of products to limit ‘carbon leakage’.

China’s new emissions-trading system will initially involve 2,225 companies in the power sector, who are responsible for a seventh of global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil-fuel combustion, according to the International Energy Agency. Under the trading program, emitters (power plants and factories) are given a fixed amount of carbon dioxide they are allowed to release a year. Over the next three to five years, China’s trading system is set to expand to seven additional high-emissions industries: petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials, iron and steel, nonferrous metals, paper, and domestic aviation. Chinese companies will start with allowances that use benchmarks based on previous years’ performances. Companies are expected to compile and submit their emissions data to the provincial branches of the ministry, which is charged with verifying the information and ensuring the system is working as planned. Failure to comply could result in a maximum fine of $4,600 or a reduction in future allowances. This may prove difficult for China, as they accounted for 28.7 percent of the world’s manufacturing in 2019, almost 12 percentage points more than the United States’ share.

The Pushback

The pushback is coming because people do not want to live in a third world country (27 gigajoules per capita is about half of Algeria’s consumption in 2019), nor do they want to spend enormous sums to transition their energy systems to non-carbon fuels. The Swiss last month rejected a referendum to impose a fuel tax and a tax on airline tickets. The British cabinet, which recently proposed major new carbon restrictions for transport industries, is split over previously announced plans to ban gas-fired home heating and the requirement for landlords to boost energy efficiency in rental units. E.U.’s new plan was attacked by furious lobbying in opposition. In France, there have been protests against a diesel tax hike that started in 2018.

In Japan, resolutions codifying aggressive corporate carbon targets were defeated at the three companies where they were proposed— Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo and Kansai Electric Power. In April, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund, the world’s largest with around $1.6 trillion under management, announced it was abandoning ESG (“environmental, social and governance”) investing.

Conclusion

Europe and China say they are progressing with climate change plans. But, certainly, in Europe and in Japan, there has been pushback to the reductions in energy use and/or to the enormous costs involved with reaching a computer projected +1.5°C temperature future. It is time for Americans to understand what President Biden’s net-zero energy system entails and what they will have to give up to get there. It could mean living with half the energy an average Algerian uses.