One of the problems with a carbon tax is that it hits poorer households particularly hard. By raising the prices of electricity, heating, and transportation—which is the whole purpose, not an unintended side effect—a carbon tax falls disproportionately on lower-income people, not in absolute dollar terms but as a proportion of their monthly budget. The advocates of a carbon tax try to fix this problem by recommending a “rebate” of its proceeds, and in some cases (such as Alberta) they even target the rebate to poorer households. They present calculations showing that poor people “make money” from a carbon tax, and so are allegedly better off.

Even if we accept these figures at face value, they don’t prove what they claim. I explained this fallacy with regard to comparable claims from the U.S.-based Climate Leadership Council (CLC). Namely, even if a particular household pays less in carbon taxes than it receives in dividend rebates, it could still be worse off, because the carbon tax makes energy (and other goods) more expensive. (That’s what taxes do, folks.) A poor household can reduce the amount it pays in carbon tax by changing its behavior, such as using less electricity and taking the bus instead of owning a car. The calculations depicting a household as a “net financial winner” from a carbon tax assess the money flows after the household adapts to the higher prices (particularly for electricity and gasoline) due to the tax.

It’s wrong to think such a household enjoys the same lifestyle as before, plus the bonus money from the government. No, the household is clearly worse off because of the price hikes, and then it’s an open question of how large a financial transfer would be needed to render it whole. Yet neither the CLC nor the Canadian-based fans of a carbon tax even seem to realize that this is the proper consideration.

The Pro-Carbon Tax Case From Canada

Andrew Leach, a carbon tax policy expert based in Canada, posted the following argument and chart on Twitter, which perfectly illustrates the fallacy I have been describing:

Leach made a similar claim in his testimony to FINA (Canada’s federal finance committee), when he said, “Alberta and BC have chosen policies with progressive outcomes – in both provinces, the bottom 40-50% of income-earners were better off with the carbon tax than without.“ (bold added).

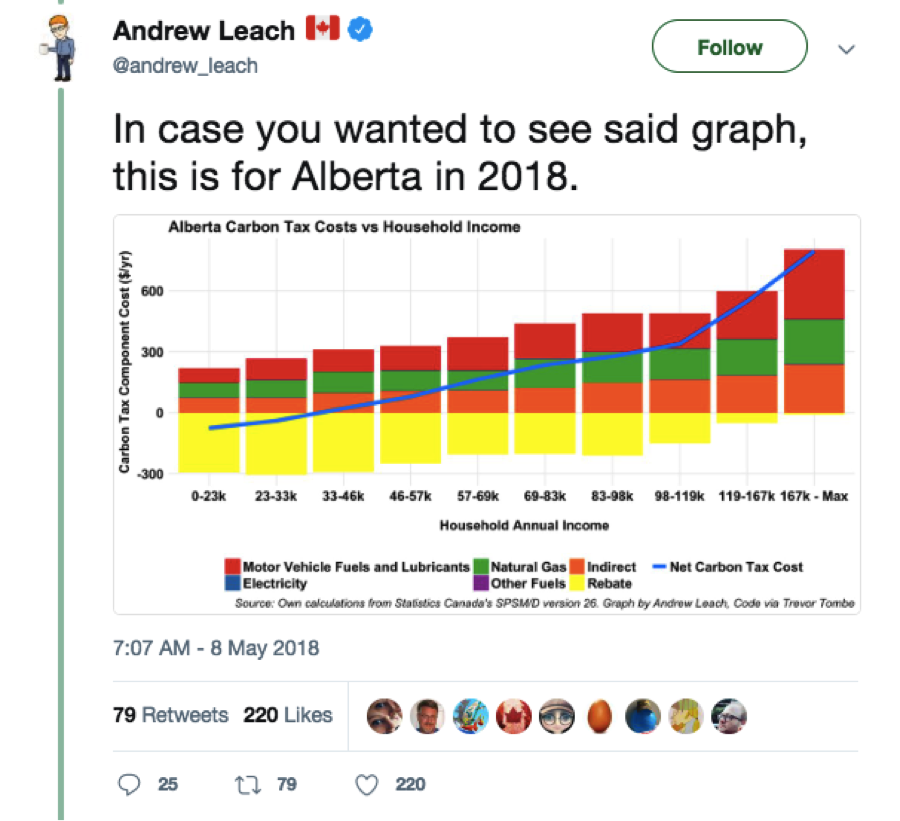

Before we explain what’s missing from Leach’s analysis, let’s make sure we understand his chart above. Because the province of Alberta sends dividend checks (tied to its carbon tax) that are means-tested—meaning that the amount of the check shrinks, the more income the household earns—and because poorer people don’t use as much electricity or gasoline, period, you can have a situation where the poorest households “make money” which is redistributed from the wealthier households that are paying the lion’s share of the total carbon tax receipts.

Just eyeballing Leach’s chart (unfortunately he wasn’t able to provide me with a broader study to elaborate on these calculations), it looks like Alberta households that earned $23,000 or less ended up receiving a “net financial benefit” from the carbon tax of about $90 per year. Specifically, they received the full $300 rebate (the yellow bar) from the government out of the carbon tax proceeds, but they had to pay about $210 per year more for various types of energy and other indirect expenses due to the carbon tax.

For the next income group ($23,000 – $33,000 per year), there is still a “net financial gain” in this sense, but it’s even smaller. Then for the next group, $33,000 – $46,000 in income per year, they are slight “losers” because the increase in their expenses exceeds the $300 annual rebate check.

As we move to higher-income household groups, the situation gets worse, because (a) their rebate check starts phasing out—that’s why the yellow bar shrinks, and (b) they spend more total dollars on various types of energy and other goods that indirectly cost more because of the carbon tax. In particular, the highest-income Alberta households were estimated to be net losers of about $850 per year. (Again, I’m just eyeballing the chart.)

Now that we understand Leach’s point, what’s wrong with it?

A Tax Hurts Even Beyond the Explicit Payment of Revenues

For one thing, the Alberta approach confirms what guys like Oren Cass and I have been saying all along: the case for a carbon tax is a shell game, at least as the debate has played out in conservative circles in U.S. politics. Leach in his commentary thinks he is zinging his own critics for flip-flopping, but I can make an analogous observation: When critics of a carbon tax point out that it will hurt GDP growth, the supporters say, “Don’t worry, we’ll use the money for supply-side tax cuts, like the corporate tax and payroll tax.” Then when critics of a carbon tax point out that it will hit poor households the hardest, the advocates say, “Don’t worry, we’ll impose a giant tax increase on the rich to fund compensation payments to the poor.” Well, you can pick one strategy or the other, but you can’t do all of the above: to protect the poor from higher energy prices, you have to use the money that was earlier earmarked for supply-side tax cuts.

But these are just quibbles. The fundamental problem with the CLC promises and the analysis from Leach above, is that it assumes the full pain of a carbon tax flows merely from the number of dollars a household actually spends because of the tax. Then, Leach thinks if a household gets a bigger dividend check than that magic number, it must be “better off” and that the people warning poor households wouldn’t be “able to heat their homes” somehow have egg on their faces.

Yet this is wrong. (I spelled out the problem using the CLC data in this earlier IER post.) To see why, let’s try something simple. Suppose a household has a minivan to get groceries and take the kids to school, and a sedan for the breadwinner to go to work. Further suppose that each week the household buys 19 gallons of gasoline among the two vehicles, or 1,000 gallons per year. Just to keep the math simple, assume that the price of gas is $2/gallon. That means our household originally spends $2,000 per year on gas for their vehicles.

Now suppose a modest carbon tax is imposed of $5/ton, which only raises the price of gasoline by 4 cents a gallon. Especially in the first year of the new tax, our hypothetical family probably won’t adjust its behavior too much. Just for a baseline, let’s assume they literally don’t change their driving habits at all. Our household thus spends 1000 x $2.04 = $2,040 on gasoline. Someone like Leach would admit, “Yep, the carbon tax has caused this household to spend an extra $40 on gas this year, which we’ll have to compare to its rebate check to see how they did.” And if in fact the household got a rebate check for exactly $40, then Leach would understandably conclude that this household broke even: what it paid in carbon taxes (in the form of higher gas prices), it got reimbursed from the government. The household could use the carbon tax rebate check to afford the same amount of gasoline as before; it could continue with its same lifestyle, and so in that sense it wouldn’t be hurt.

However, this logic breaks down when the household does alter its behavior in response to the new carbon tax. For example, now suppose our hypothetical carbon tax is increased to $57/ton, so that the price of gas jumps up to about $2.50. (In other words, the carbon tax would add 50 cents to the price of gasoline.) If our family persisted in its original lifestyle, consuming 1,000 gallons of gasoline per year, this new level of the tax would translate into an extra $500 in annual expenses just for driving.

However, at this much higher tax rate, our household won’t keep buying the same amount of gas. And remember—this is what the carbon tax proponents WANT to happen. The whole point of a carbon tax is to discourage driving in conventional vehicles. Let’s suppose that at the higher price of $2.50 per gallon, our household cuts back on the number of trips it takes in the minivan, so that it only ends up consuming (say) 900 gallons of gasoline per year, so that it spends $2.50×900 = $2,250 per year on gasoline.

Now here is where things get interesting. I believe (but can’t confirm since I don’t have access to the raw calculations) that the proponents of a carbon tax would report that this household now spends 50 cents x 900 gallons = $450 per year towards the carbon tax. So if the government were to send this household a rebate check for exactly $450, then Leach would conclude the whole thing was a wash—this particular household got back exactly what it paid out in carbon taxes, and so presumably its ability to drive around hasn’t been reduced.

And yet I can show you that that’s not true at all. To see why, consider: Suppose the household tries to go back to its original budget, before the carbon tax was imposed. So it spends the same amount on everything else, leaving the original $2,000 left in the family budget earmarked for driving.

Now on top of the household’s original income, in the carbon tax scenario it has the extra $450 rebate check. So suppose the household throws that into the category for “transportation.” In other words, the household is still buying the same amount on food, rent, entertainment, etc. as it was originally (before the carbon tax), but now it is earmarking a full $2,450 towards gasoline. Even so, at the higher price of $2.50 per gallon, that works out to $2,450 / $2.50 = 980 gallons of gasoline., which is 20 fewer gallons that what the household bought originally.

In other words, with this particular example, we can see that once the dust settles, the household is clearly worse off than in the status quo before there was a carbon tax. In our example, if the household spends the same amount of money on other goods and services, and then tries to use the government’s rebate check in order to maintain its original lifestyle, it won’t work. The math doesn’t add up. Once the household adjusts to the higher carbon tax, even if the government sends a rebate check equal to the “total carbon taxes paid” in the form of higher prices on the units that the household still chooses to buy at the higher price, then the household ends up with a reduced standard of living. Leach’s technique for calculating “winners” from a carbon tax is leaving out a very important consideration. His technique would say that our hypothetical household is neither harmed nor helped by the carbon tax, but we’ve seen it is clearly made worse off: If it tried to maintain its original lifestyle, it would be 20 gallons of gasoline short.

Conclusion

The whole point of a carbon tax is to render certain types of electricity and transportation more expensive, to induce households and businesses to reduce their consumption. After the government imposes a new carbon tax and then lets people adapt, if we then ask, “How many dollars does this type of household pay out-of-pocket because of the tax?” then we are understating the pain it has caused the household. Part of the way to deal with the tax is to minimize liability by getting out of the activity that’s being zapped.

Because of this basic principle, the calculations attempting to assess “winners” (while ignoring the “losers”) from a carbon tax rebate scheme fundamentally mislead the public, whether the proponents are aware of this issue or not. Even if a poor household “makes” $50 or even $100 a year from a rebate scheme, it could still be worse off from the higher energy and transportation prices it must pay due to the carbon tax.