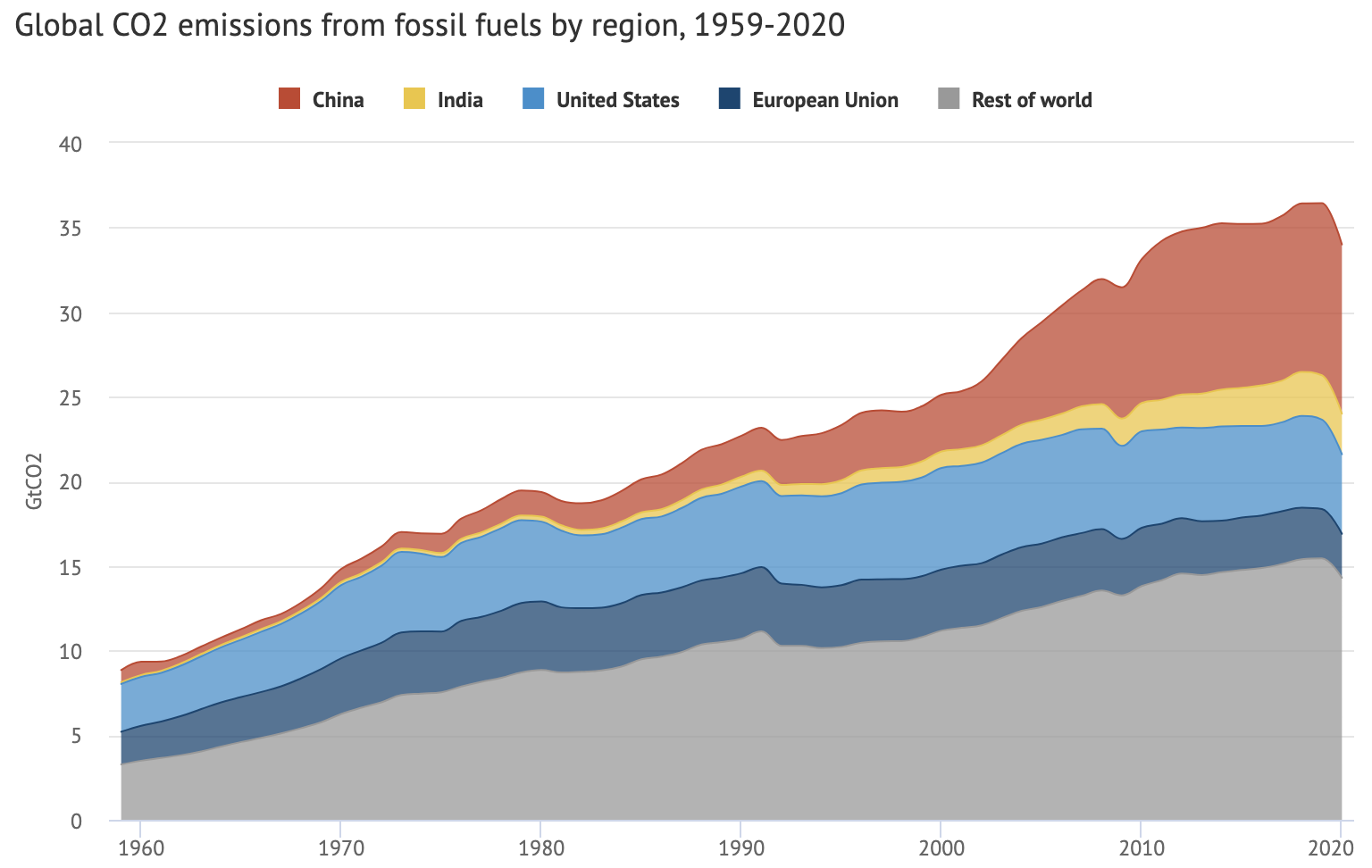

Due mainly to the lockdowns from the coronavirus pandemic, carbon dioxide emissions are estimated to have declined by 7 percent globally in 2020, while U.S. carbon dioxide emissions are estimated to have declined more—by 10.3 percent—to the lowest level since 1990, three decades ago. Despite China’s carbon dioxide emissions falling during the first 4 months of 2020, they are expected to have increased as the country had an increase in its GDP of 2.3 percent in 2020, according to its National Bureau of Statistics—the only major economy to have its economy recover from the coronavirus pandemic. The International Energy Agency’s Birol agrees with this expected increase in China’s carbon dioxide emissions in 2020.

The World

The 7 percent annual decline in global carbon dioxide emissions is the largest absolute drop in emissions ever recorded, and the largest relative fall since the second world war. Carbon dioxide emissions have fallen in most of the world’s biggest emitters, the United States, the European Union, and India. This year has also seen the first fall in global emissions since a 1.3 percent drop in 2009, which was driven by the global financial crisis that started in 2008.

The decline in carbon dioxide emissions in the EU27 is expected to be 11 percent in 2020. Carbon dioxide emissions from oil, natural gas and cement are estimated to drop by 12 percent, 3 percent, and 5 percent, respectively. Consumption of both oil and natural gas, however, have been rebounding in recent years.

A 13-percent decline in emissions is predicted in the UK this year as a result of the extensive lockdown measures introduced in March, plus the second wave of the pandemic. The only country that is expected to have a larger drop in carbon dioxide emissions is France—by 15 percent.

Carbon dioxide emissions in India – the world’s third largest emitter – increased by just one percent in 2019 before the pandemic hit. This was a result of economic turmoil and strong hydropower generation. Despite a trend of growing emissions in India from oil and coal over the past decade – alongside moderate growth in natural gas and cement – the pandemic is expected to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 7 percent, 10 percent, 2 percent and 15 percent, respectively, in 2020 in these four areas. 2020 is the first year in four decades in which emissions in India are expected to decline—a 9-percent overall reduction.

United States

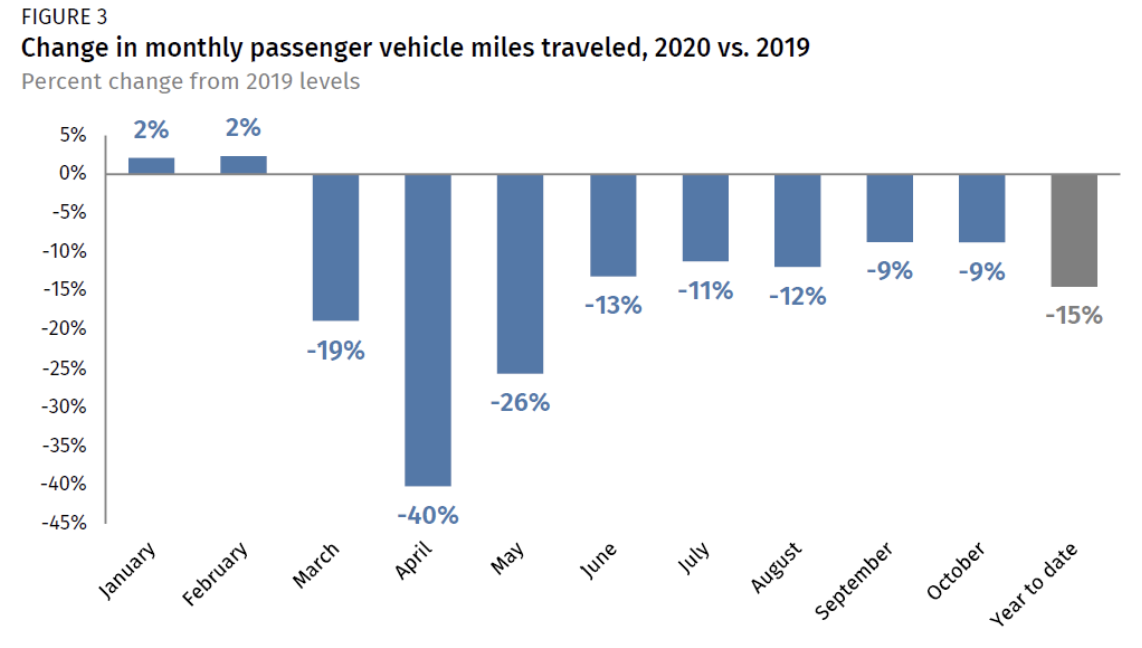

The biggest drop in U.S. carbon dioxide emissions was in the transportation sector. For the first 9 months of 2020, carbon dioxide emissions in the transportation sector dropped 15 percent—similar to air and road passenger travel miles, which fell 15 percent below 2019 levels for the first 10 months of 2020. The steep drop-off in air travel was the biggest contributor, with jet fuel consumption falling 68 percent at the peak of lockdowns in April and May. Gasoline (primarily from passenger vehicles) was down 40 percent in April and May and diesel (used in shipping and trucking) was down 18 percent. Jet fuel demand recovered somewhat bouncing back to around 35 percent below 2019 levels in December based on preliminary data. Diesel spurred by holiday deliveries returned to near 2019 levels in December.

Passenger travel bounced back quickly after travel restrictions were lifted in May and June in most regions. The first round of shelter-in-place orders led to a sharp decline in passenger vehicle travel (measured by vehicle-miles-traveled), dropping 40 percent at its peak in April. But travel recovered quickly by June (down only 13 percent) with a more gradual recovery through October (the last month of available data).

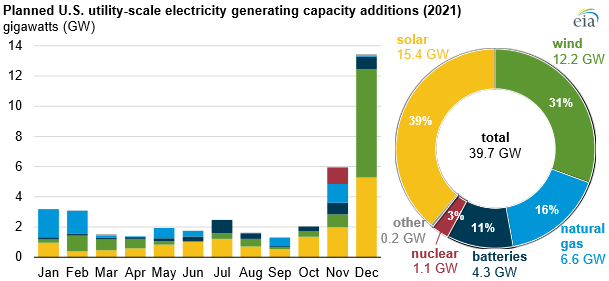

In the U.S. electric power sector, carbon dioxide emissions dropped 12 percent for the first 9 months of the year. The pandemic hastened current trends, with coal use declining and natural gas and renewable energy increasing. Those trends are expected to continue with solar and wind power accounting for 70 percent, 39 percent and 31 percent, respectively, of planned new power installations for 2021 and natural gas accounting for 16 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The new nuclear reactor at the Vogtle power plant in Georgia will account for 3 percent of the new capacity and batteries for 11 percent. Total new capacity announced by utilities for 2021 is almost 40 gigawatts.

Taxpayers will pay subsidies for the solar, wind, and battery capacity coming on line this year. According to EIA, the average capital cost for solar PV is $1,331 per kilowatt. With 15.4 gigawatts of announced capacity, and an investment tax credit of 26 percent, taxpayers will pay $5.3 billion for the solar capacity subsidy in 2021. Battery technology also gets the same subsidy. With 4.3 gigawatts of announced battery capacity at an average cost of $1,383 per kilowatt according to EIA, taxpayers will pay $1.55 billion in subsidies. Wind also gets a tax subsidy; it is on the amount of electricity production from the wind turbines and lasts for the first ten years of their operation.

China

China’s economy shrank 6.8 percent in the January-March period compared with 2019—the first contraction in nearly half a century as travel and business was nearly halted. Since then, the economy has improved steadily, finishing the year with growth of 6.5 percent in the last three months compared to the same period in 2019. Factories across China are filling overseas orders and cranes are busy at construction sites—this boom is expected to drive the economy in 2021.

When Wuhan was still under lockdown, China moved to get manufacturing up and running in other areas. The government provided long-haul buses to get workers from their home villages to factories after the Chinese New Year. State-owned banks extended special loans to factories, while many government agencies gave partial refunds of business taxes that had been paid before the pandemic.

Beijing also ramped up its infrastructure spending. With every major city in China already connected with high-speed rail lines, new lines were added to smaller cities and new expressways crisscrossed remote western provinces. Construction companies turned on floodlights at many sites so that work could continue around the clock.

Despite the trade war and tariffs, American and European companies turned to China for parts and goods when factories elsewhere struggled to meet demand. Factories within China turned to nearby suppliers to replace imports as transoceanic supply lines became less dependable.

Exports and infrastructure fueled much of the growth over the past year. China’s exports grew 18.1 percent in December compared with the same month a year earlier, and were up 21.1 percent in November. Fixed-asset investment in everything from high-speed rail lines to new apartment buildings increased 2.9 percent last year.

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicts that the country’s economy would expand 7.8 percent in 2021. If it does, it would be China’s strongest performance in nine years. With that expansion, the world can expect increased carbon dioxide emissions as China uses mainly fossil fuels to fuel its economy and is increasing their use at a breakneck speed.

Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency, expects China’s oil demand to be slightly higher in 2020 than it was in 2019, and its natural gas demand to be much higher in 2020 compared to 2019. China has been and is being hit with an extreme cold spell that will increase its heating fuel demand.

Conclusion

Most countries are expected to lower their carbon dioxide emissions in 2020 due to lockdowns caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The only exception is China, whose economy grew by 2.3 percent in 2020 and who is taking advantage of the downturn in manufacturing in other countries, increasing its exports tremendously by the end of 2020. It appears China is very serious about spurring its economic growth for its citizens’ welfare and is using more energy—fossil energy—to do so.