Breathe a Little Easier is part of our ongoing effort to explain the role that energy has played in improving human living standards over the past two centuries. This project examines trends in air quality in the U.S. in order to push back at the doom-and-gloom narratives that dominate so much of our thinking about energy and the environment today.

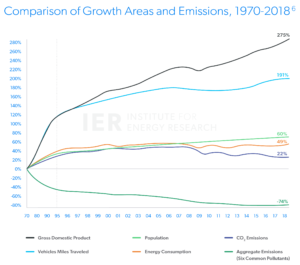

One of the best pieces of evidence supporting the Environmental Kuznets Curve and the Environmental Transition Hypothesis can be seen in air pollution in the United States. As the chart below shows, between 1970 and 2018, U.S. gross domestic product increased 275 percent, vehicle miles traveled increased 191 percent, energy consumption increased 49 percent, and U.S. population increased by 60 percent. During the same time period, total emissions of the six principal air pollutants dropped by 74 percent.

About the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) & The Environmental Transition Hypothesis (ETH)

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) argument is an application of economist Simon Kuznets’ observations on income inequality to environmental quality. Originally, the EKC purported to show that as economies grow from a pre-industrial state into what we know as a developed state, economic inequality initially surges, but eventually levels off and finally falls. The resulting curve takes the form of an upside-down “U.” The extension of the Kuznets Curve to environmental quality is that as economies grow from a pre-industrial state into what we know as a developed state, environmental degradation initially surges, but eventually levels off and finally falls.

The extent that this is an observable pattern, much can be said about its causes. One clear aspect is industrial efficiency gains driven by profit and loss. Using less to achieve more is part and parcel with profitability, so it would make sense that as firms and industries mature, they become better at maximizing their production and minimizing waste. Another causal factor is human-environmental tolerance and its status in a values hierarchy. In keeping with Kuznets’ inequality curve, it is argued that people are very tolerant of environmental degradation early in the economic development process, but that when income allows for baseline human needs—food, clothing, shelter—to be met, concerns for environmental quality are expressed. This turning point begins the environmental restoration process. At some point consumers become rich enough to use some of their growing income to implicitly “buy” cleaner air, more nature preserves, etc.

The Environmental Transition Hypothesis (ETH) observes the same increase, flattening, and then decrease in environmental degradation. There is an abundance of data that supports the EKC and ETH. What distinguishes the ETH is that it is not income per se that initiates the environmental transition, but rather the availability of technology.

Technology can proliferate and positively influence environmental outcomes in countries that may lag behind in economic development allowing them to bypass stages of environmental harm that befell early industrializers.

Because of such improvements the human population has risen drastically in the past half-century without the costs to the earth that were in vogue in the 1970s. Thanks to innovation, today human beings live healthier, wealthier lives without the effects on the land, water, and air quality that earlier generations precipitated.

One of the best pieces of evidence supporting the Environmental Kuznets Curve and the Environmental Transition Hypothesis can be seen in air pollution in the United States.

Standard explanations attribute this progress to regulations like the Clean Air Act and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), but it is important to understand that the trend started decades before Congress passed the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970.

In their 2007 book, Air Quality in America, Joel Schwartz, and Steven F. Hayward demonstrated that air quality had been improving long before the EPA was established in 1970.

The data indicate that thanks to technological gains, the improved servicing of human wants and needs does not require ever-expanding resource consumption and waste. Further, it suggests that pessimism about our environmental future is unwarranted. Wealth creation and technological improvements have enabled human beings to minimize waste while expanding production.