President Biden has announced a much stricter emissions target for the United States than former President Obama did when he committed the country to the Paris Agreement in 2015. Biden’s pledge is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent from 2005 levels by the end of this decade. That pledge represents a near-doubling of the target that Barack Obama committed the nation to, when he vowed to cut emissions between 26 and 28 percent compared to 2005 levels by 2025.

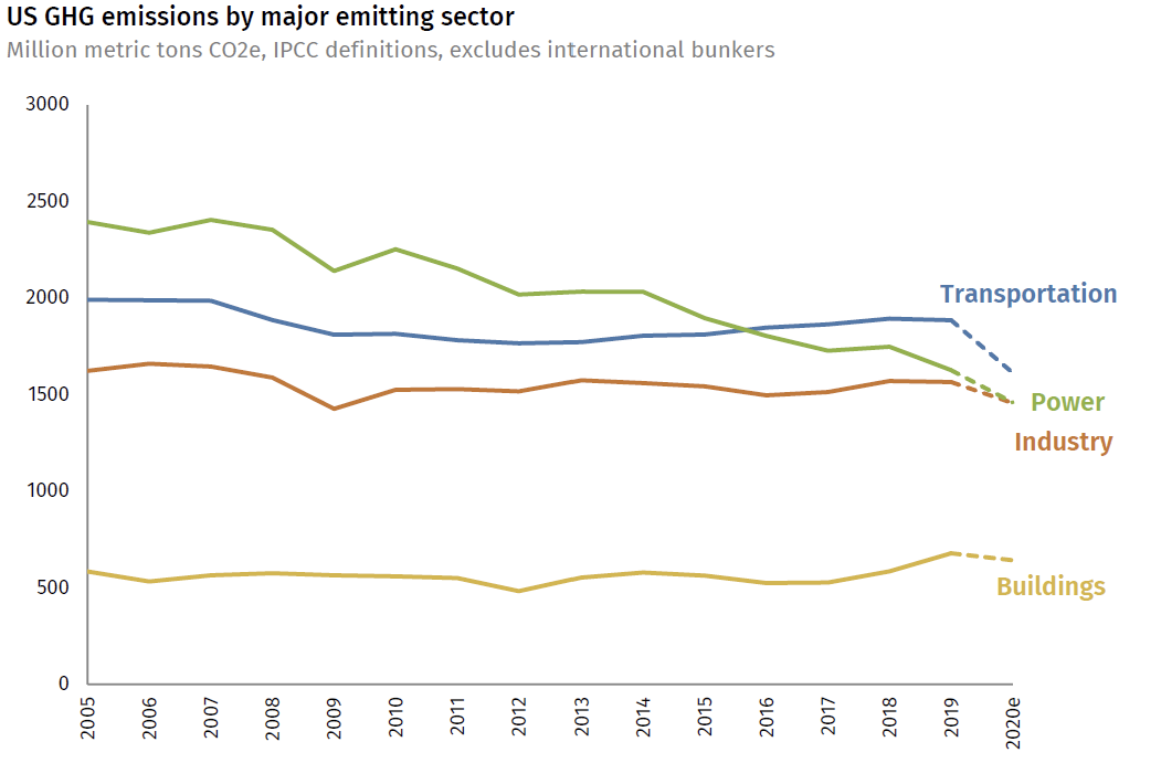

In 2019, the most recent year for which complete data are available, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions were 13 percent below 2005 levels, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 are projected to be down 21 percent from that 2005 baseline, due largely to a slowdown related to the coronavirus pandemic, which means that these emissions will likely increase as the U.S. economy improves. It is important to point out that carbon dioxide-creating fossil fuel sources currently provide 78 percent of total U.S. energy use.

Doubling the target of reductions from Obama’s aggressive targets is a big deal. To get a sense for the magnitude of Biden’s pledge, note that doubling the target by employing a tax would require more than doubling the tax rate on energy because people move away from purchasing highly taxed items. It would also more than quadruple the economic harm inflicted from Obama’s pledge and kill good-paying jobs. The Obama administration, with its regulatory strategy, was inflicting great economic damage in the pursuit of much smaller reductions than Biden’s.

How will the Biden administration pursue its goal? The actual plan has not yet been revealed, but with a target that ambitious, it will not matter what is in the American Rescue Plan, American Jobs Plan, American Family Plan, or any other American plan that Biden throws out there. The growth prospects of the American middle class will be determined and probably undermined by the implementation of his pledge, which will be scoped out and announced later this year. Given that the implementation plan has yet to be designed, it is surprising that Biden can believe such a pledge is even feasible. And further, to believe it is feasible in 9 short years.

In terms of policies to get there, investing in clean energy, resilient infrastructure, electric vehicles and a reliable electric grid are likely to be a few ways to spend taxpayers’ money on unneeded investments. Others will be limiting greenhouse gas emissions from coal and gas power plants and regulating methane emissions from oil and gas fields. However, it will likely take much more than these items to attain a 50-percent reduction. Many see it as a dramatic overhaul of American society.

Biden’s Virtual Summit Meeting Commitments

All 40 world leaders the president invited to the virtual summit attended, including those from China and India. The U.K. and European Union committed to slash emissions by 68 percent and 55 percent, respectively, by 2030.

China, the world’s biggest emitter, vowed to reach peak emissions by 2030 and be carbon neutral by 2060—pledges it has made before. The United States and China have agreed to cooperate on climate change despite division on issues like trade and human rights. However, the Chinese minister, Wang Yi, warned that Chinese cooperation would depend on how the United States responded to Beijing’s policies regarding Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Xinjiang. China’s greenhouse gas emissions come largely from burning coal. China is the world’s largest coal consumer, and it is building new coal plants at home and abroad, even as the United States and Europe are retiring their coal plants.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced an India-U.S. Climate and Clean Energy Agenda Partnership for 2030 and re-confirmed the nation’s vow to install 450 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2030.

Canada vowed to reduce 2005 emission levels by 40 to 45 percent by 2030. Brazil President Jair Bolsonaro vowed to end deforestation in the country by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 if the Biden administration would provide $1 billion to pay for conservation efforts in the Amazon rainforest.

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said the country will pledge to curb emissions by 46 percent by 2030 compared with 2013 levels. South Korea President Moon Jae In said that Korea will end public financing of coal-fired power plants overseas and plans to unveil a stronger emissions reduction pledge.

Russia President Vladimir Putin broadly pledged to “significantly” reduce the country’s emissions in the next three decades and said Russia makes a big contribution in absorbing global carbon dioxide. According to Putin, Russia has nearly halved its emissions compared to 1990 and he called for a global reduction of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

Note, however, that neither India nor Russia made any new pledges to reduce oil, natural gas, or coal. Neither did Australia, Indonesia, or Mexico. Some countries said that they were being asked for sacrifices even though they had contributed little to the problem, and that they needed money to cope.

Conclusion

It is easy to make a pledge. It is harder to implement it. It is also very hard to make others adhere to their pledges upon which your own good-faith pledge is made. China, for example, has made statements of concern about carbon dioxide before, yet continues to massively fund coal plants and will surpass the United States in refinery capacity this year. Words are one thing, but actions speak something else. Making pledges, especially ones that are this monumental, without knowing their feasibility nor their impact is not representative of leadership if it turns out other parties ignore their commitments.

If the U.S. enforces the Biden pledge, energy prices for consumers will increase and most likely be regressive as lower-income Americans spend more of their earnings on energy than higher-income Americans.