According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the renewable fuel standard (RFS), a federal program requiring the use of biofuels in gasoline supplies, has not lowered gasoline prices at the pump nor significantly reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Most of the biofuels meeting the standard are composed of corn-based ethanol, which has few environmental advantages compared to gasoline. Further, gasoline prices outside of the Midwest, where most of the corn is grown, likely increased by a few pennies a gallon because of the Renewable Fuel Standard, while declining slightly in areas with ethanol plants. GAO indicates that those price effects diminished over time as refiners installed equipment to meet the fuel-blending requirement of the RFS “that, over time, reduced refining costs for gasoline.”

The Renewable Fuel Standard

Congress enacted the RFS as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and expanded it in the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA). The RFS mandates that gasoline and diesel sold in the United States contain increasing amounts of biofuels. The most common biofuel currently produced in the United States is corn-based ethanol, which is distilled from the sugars in corn. Congress passed the RFS to increase energy independence and security and to increase the production of renewable fuels, which it saw as a way to decrease greenhouse gas emissions.

The RFS in 2005 required that a minimum of 4 billion gallons of biofuels be blended into gasoline in 2006, increasing to 7.5 billion gallons by 2012. The 2007 law expanded the amounts of biofuels to be blended into gasoline from 9 billion gallons in 2008 to 36 billion gallons in 2022. Those requirements were divided between corn-based ethanol, which was set at 15 billion gallons, and advanced biofuels, which was set at 21 billion gallons in 2022. Advanced biofuels emit less greenhouse gas emissions than corn-based biofuels but were not commercially available at the time of the legislation.

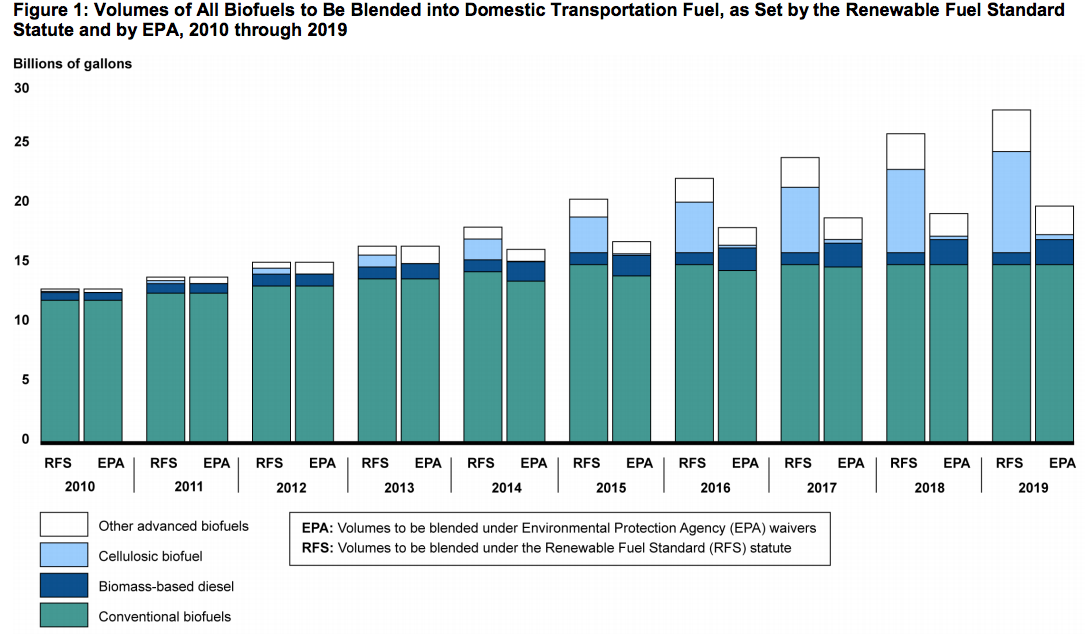

Unfortunately, the original advanced biofuels requirement was never met because the technology never reached full commercial availability due the high-cost of production. As a result, the Environmental Protection Administration reset the levels of advanced biofuel production required each year to levels that were more feasible to achieve. The graph below compares the levels of conventional biofuels (corn-based ethanol) and advanced biofuels (biodiesel, cellulosic ethanol, other advanced ethanol) required by the RFS and required by the EPA for each year between 2010 and 2019.

Compliance with the program was tracked through the use of renewable identification numbers (RINs) associated with biofuels blended with petroleum-based fuels. Unsurprisingly, there were numerous problems associated with the RINs, including possible fraud, their effect on small refiners, price volatility, and the location of the point of obligation.

Analysis and Findings

Because the reduced demand for transportation fuels and volatility in the global price for crude oil affected the retail price of gasoline, GAO could not measure the effect the RFS had on gasoline prices nationwide. As a result, the agency developed an econometric model and analyzed various state RFS programs. The state-level analysis isolated the effect of ethanol mandates on retail gasoline prices in five states—Hawaii, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, and Washington—and used the other states to control for other factors that influenced retail gasoline prices over time. GAO also interviewed experts.

The agency found that the nationwide RFS was associated with modest price increases outside of the Midwest. Variations in the gasoline prices outside of the Midwest depended on state-by-state variation in the costs to transport and store ethanol. The Midwest had lower transportation costs and the necessary storage infrastructure because it was already producing ethanol, while other regions began blending ethanol later due to the RFS requirements. These regions incurred new transportation and storage infrastructure costs, which resulted in slightly higher gasoline prices (a few cents per gallon) compared to those in the Midwest states.

GAO also found, through interviews with experts, that the RFS has had a limited effect on greenhouse gas emissions and that it is unlikely to meet the greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals envisioned for the program through 2022.

Other Recent Studies

The EPA published a report last year indicating that corn-based ethanol and soybean-based biodiesel are hurting water quality and that the RFS may be increasing the number of acres being planted for biofuels. More recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released a study in April that found corn-based ethanol’s greenhouse gas emissions were 39 percent lower than gasoline over the entire life cycle—from the production of raw materials to processing to combustion in vehicles.

Conclusion

The RFS became law in 2005, was modified by legislation in 2007, and has required increasing use of biofuels annually. The enactors believed that greenhouse gas reductions would come from increasing non-corn-based ethanol. That was not the case because advanced technologies for biofuels did not become economic, causing EPA to have to reset the required volumes from those in the legislation. The early expectation was that gasoline prices at the pump would decline, but that was also not the case because of transportation and infrastructure costs related to ethanol. Further, issues arose regarding RINs that indicated possible fraud and unfairness to small refiners, among other issues. Additionally, ethanol use in boats, lawn mowers, and other small motor applications caused major problems, frequently requiring large repair costs.

Energy independence and national security were the arguments used for the passage of the initial ethanol mandate in 2005 and its 900-percent increase two years later. It was believed that the United States needed to displace foreign oil imports with domestic fuel for our economic and national security. As it turned out, the combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing vastly changed the United States and the world and turned the foreign oil dependency of 2005 and 2007 into a moot point. The United States is now the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas, and is becoming an exporter of both. Further, ethanol was already being used by refiners as an oxygenate and fuel extender; forcing mandates for additional ethanol use at levels far greater than the demand for transportation fuels could handle did an injustice to the American public.