The federal mandate to blend corn-based ethanol into the U.S. vehicle fuel mix is an economically absurd practice. On a level playing field, conventional gasoline would be used for the foreseeable future, as it is the most efficient method (all things considered) to deliver energy to U.S. vehicles. At most ethanol would have a small share of the market in the absence of federal government support.

However, a recent study from Iowa State University argues that the growth in ethanol production from 2000 – 2010 has suppressed gasoline prices by an average of 25 cents per gallon and 89 cents per gallon in 2010. The study also warns that if ethanol production were suddenly halted, gasoline prices could rise a shocking 41 to 92 percent.

As we’ll see, these figures are very misleading, because they look at the history of conventional gasoline refinery capacity (in the face of government-supported ethanol output) and assume it wouldn’t have been any different over the last ten years, had the government never supported ethanol. Once we realize the trick involved, the study’s pro-ethanol conclusions fall away.

The Iowa Study’s Claims

The study is heavy on econometrics jargon; quoting portions of it would be virtually useless in conveying to the layperson how the study actually gets its results. The closest to a plain English explanation comes in the authors’ discussion of their final result:

In the scenario in which ethanol is totally eliminated from domestic supply, the system [of equations] specified [earlier in the paper] is used to simulate the gasoline price responses after taking into account (i) the gasoline stocks at the level of 2010, and (ii) the full utilization of the spare capacity of US oil refineries in 2010. Three sets of simulation results are generated under different levels of elasticities (high, medium, and low). The results summarized in Table 4 indicate that if the ethanol supply were eliminated from the domestic gasoline market, wholesale gasoline prices may change by 41%– 92% in the short run depending on the sensitivity of producers and consumers to prices. (“The Impact of Ethanol Production on U.S. and Regional Gasoline Markets: an Update to May 2009,” [.pdf], p. 5.)

As this quotation explains, the study takes as a given that U.S. refining capacity and gasoline stocks start at their actual values for 2010, and then combines them with traditional measures of how gasoline prices move in response to increases in demand, in order to estimate the impact of a sudden disappearance of the entire ethanol industry. Not surprisingly, such an unexpected and massive event would lead to massive spikes (in the short run) of gasoline.

Does the Iowa Study Justify Government Favoritism for Ethanol?

Clearly the groups promoting this study want the reader to draw the inference that the U.S. government’s preferential tax treatment of ethanol is good for U.S. consumers. Yet the study doesn’t prove this at all. The reason conventional gasoline refining capacity is at its current level, is the existence of such a massive program of support for ethanol over the years.

If the U.S. government didn’t give special tax treatment and other mandates to guarantee ethanol a fraction of the market, gasoline would have filled the gap. In other words, government policies have displaced conventional gasoline from the market, and that’s why a sudden removal of all the ethanol would lead to a temporary shock in the gas market. Yet the fact remains that consumers would have been better off, had the government never intervened to support ethanol in the first place.

For an analogy, suppose Chick-fil-A begins running commercials touting the advantages of eating white meat over burgers. In response, the burger joints put out statistics claiming that if all the McDonald’s and Burger King franchises magically disappeared next Tuesday, then there wouldn’t be enough chicken sandwiches to feed Americans at lunchtime. Therefore, the burger joints would conclude, Americans should disregard the Chick-fil-A ads, because clearly there aren’t enough chickens to go around.

Such an argument would be absurd. If American consumers stopped eating burgers and switched to chicken, then McDonald’s and Burger King franchises would close down (or revamp their menus) and be replaced by Chick-fil-A and other such restaurants. The nation’s cattle ranchers would lose business, but the chicken farmers would see growing business. The market would switch over to cater to what consumers wanted.

A similar process would occur if the government treated ethanol the same way it treated gasoline. On a level playing field, it would be unprofitable for refiners to blend billions of gallons of ethanol into their mix, certainly in the long run. The market would gradually adapt to what made economic sense, namely the refining of oil into conventional gasoline. The share of ethanol would shrink, and ultimately consumers and taxpayers would be richer than they otherwise would have been.

While ethanol would have likely penetrated the market without government subsidies, its production would not have reached the levels that were mandated by the government by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007.

Explaining the “Regional Effect” of Ethanol Production on Gasoline Prices

The best way to see that the ostensible benefits of ethanol are due to its displacement of traditional gasoline refining, is the regional effect noted by the paper. The authors note in the abstract:

This report…concludes that over the sample period from January 2000 to December 2010, the growth in ethanol production reduced wholesale gasoline prices by $0.25 per gallon on average. The Midwest region experienced the biggest impact, with a $0.39/gallon reduction, while the East Coast had the smallest impact at $0.16/gallon.

The wording in the quotation above is extremely misleading. The reader gets the impression that gasoline prices were zooming upward, only to be held back by the farsighted politicians who fortunately kickstarted an ethanol program.

In particular, since the “Midwest region experienced the biggest impact” of 39 cents per gallon, while the East Coast “had the smallest impact” at only 16 cents, the innocent reader might get the idea that over the period in question (from January 2000 to December 2010), gasoline prices increased more in the East Coast than in the Midwest. After all, the quotation above makes it sound as if ethanol “helped” drivers in the Midwest 23 cents more than it helped drivers on the East Coast.

Yet the data don’t show this at all, as illustrated in the following table (constructed from EIA’s interactive database) of average refiner prices (through retail outlets) of regular gasoline over the period and regions in question:

[table id=39 /]

As the table above demonstrates, motorists in the Midwest got nowhere near the ostensible 23-cent relative advantage from ethanol, compared to the poor saps on the East Coast. In reality, the roughly 4-cent advantage held by the East Coast (in terms of cheaper wholesale gasoline prices) prevailing on January 2000, had been whittled away to basically zero by December 2010. Looking at the data from a different angle, wholesale prices increased about 5 cents per gallon more in the East Coast, than they did in the Midwest, over the period in question. (The two approaches are yielding apparently different numbers—namely 4 cents in the bottom row versus 5 cents in the far-right column—because of rounding. The two approaches actually give the same number.)

When we step back and think about it, the result reported by the Iowa study couldn’t possibly be right—at least not in the way most casual readers would have interpreted it. If the boost in ethanol production really held wholesale gasoline prices in the Midwest down by 39 cents, versus a smaller impact of only 16 cents in the East Coast, then retailers in the East Coast would have wanted to buy Midwest-produced gasoline because of the 23-cent-per-gallon advantage. Special environmental regulations particular to each region would not have permitted that purchase directly (i.e. East Coast gas stations can’t literally use gasoline currently produced for Midwest specifications), but if the price discrepancy were large enough, it would make sense for the Midwest refiners to cater to the East Coast market. Competition between regions would still tend to suppress the large gaps in wholesale prices implied by the Iowa study results..

As the data in the table above show, the alleged 39-cent versus 16-cent savings of ethanol don’t exist out in the actual price histories. So where do these numbers come from, and why is the “advantage” to the Midwest so much higher than for the East Coast?

As we explained in the previous section, the study generates its estimates by looking at conventional gasoline refining capacity, inventories of gasoline, and other factors for a certain region (or the country as a whole), and then simulating what would happen if the ethanol production in that region (or country) disappeared.

The reason the effect appears so much more dramatic in the Midwest—thus giving rise to the high 39-cent figure, versus the low 16-cent figure on the East Coast—is that there is naturally more ethanol production in the Midwest. Consequently, industry in the Midwest adapted over the period 2000-2010 to the ethanol availability, which only existed because of federal support. That’s why the Iowa study’s technique spits out the “fact” that ethanol production has held down gas prices more in the Midwest than anywhere else in the country, because the conventional oil refining system there has been relatively displaced by the (artificial) growth in the ethanol sector.

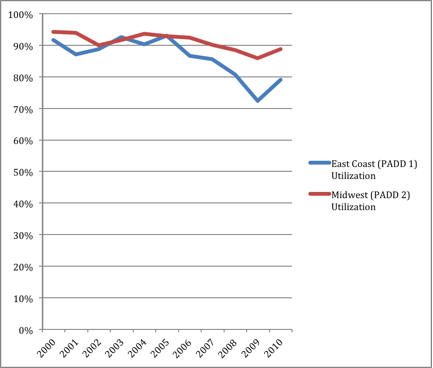

One way to see this in the data is to look at the change in refining utilization rates between the Midwest and the East Coast over the period in question:

Utilization of Crude Oil Refinery Operable Capacity

Source: EIA

As the chart shows, since 2005 oil refinery utilization rates have dropped more in the East Coast than in the Midwest. Loosely speaking, when it comes to refining oil into gasoline, the situation in the Midwest is much “tighter” than on the East Coast.

More investigation would be needed to determine exactly how these different paths of adaptation played out. Yet the numbers show the sense in which the Midwest currently has less “room for error” with respect to conventional refining of crude oil. This factor is partly responsible for the Iowa study’s regression results, showing that ethanol “held down” gas prices more in the Midwest than on the East Coast.

To reiterate the most important point: When the Iowa study says ethanol “held down” gas prices, it is very misleading. The actual wholesale prices between the two regions have stayed within 5 cents of each other over the decade. Rather, what happened is that the development of the (federally supported) ethanol sector retarded the development of the rest of the market, either in capacity or its ability to import gasoline produced elsewhere (such as Canada). We should not conclude that if the government had never supported ethanol, then drivers in the Midwest would currently be paying 39 cents more per gallon.

Conclusion

The recent Iowa State study claiming that ethanol production has suppressed the growth in gasoline prices is very misleading. It takes for granted the current refinery capacity and other infrastructure that industry uses to deliver gasoline to motorists, without realizing that federal policies over the years have distorted the development of these markets. Ethanol only survives in the market place at its current levels because it is propped up by artificial mandates and preferential tax treatment.

The regression analysis of the Iowa study doesn’t accurately capture the timeline that would have occurred had the free market been allowed to operate. Of course a sudden disappearance of all ethanol would cause a bigger price spike in the Midwest than in the East Coast. That’s because the artificial federal support has displaced the development of oil-based gasoline delivery in the Midwest more than in other regions. The fact still remains that ethanol (at its current market share) is very inefficient. Taxpayers and consumers would be richer if the government dropped its support programs for it.