President Trump’s pursuit of energy dominance is being challenged not just from the production of energy, but from the transport of it as well. With the greater production of oil and natural gas comes the need for more pipelines to economically ship the fuel to homes, businesses, refineries and export locations. The shortage of natural gas pipelines is well understood during the winter months in New England when electricity and natural gas prices have skyrocketed due to weather conditions increasing demand and hindering the availability of supplies. But, there are pipeline shortage problems in other areas as well. In Texas, there is a shortage of pipelines to move oil from production areas to markets. And, in Canada, oil producers suffer discounted prices due to a shortage of pipelines to move oil sands to markets.

Northeast

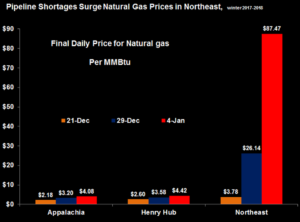

Natural gas prices in some parts of the Northeast (New England, New York, and New Jersey) increased by 60 to 70 times their normal rates because of the lack of pipeline capacity in the region. Natural gas is used in the Northeast for generating electricity and heat, providing over half of the power in the region. Due to a lack of pipeline capacity, heating oil was forced to make up about 35 percent of New England’s electricity this past winter, raising electricity prices. Annual residential electricity rates in the Northeast are over 50 percent higher than the national average–about 19 or 20 cents per kilowatt hour, compared with the national average of 12 to 13 cents.

Texas—Permian Basin

Oil producers are producing record volumes from the Permian basin in Texas–the source of most of the nation’s shale oil production—while the region’s energy infrastructure is being sorely strained. Pipelines from west Texas to the Gulf Coast are full, and new lines will not be completed until next year. While rail has been an alternative to pipelines, they are mostly dedicated to bringing needed supplies (such as sand) to shale oil producers. These shipping bottlenecks could limit the rate of growth of future shale oil production, and result in lower oil prices to producers as pipelines fill to capacity. Consumers do not share in these lower prices, however, as the differential is absorbed by using less efficient transportation such as trains and trucks.

Currently, Permian basin oil is selling at a discount of $13 to $16 a barrel below similar contracts. For example, while U.S. crude futures were trading at around $71 a barrel, Midland, Texas-based shale oil was selling at around $58 a barrel. The lower price has made East Coast refiners eager to purchase the Texas crude, raising Gulf Coast to East Coast oil trade to three-year highs. In the December-to-February time period, an average of 2.8 million barrels was shipped from the Gulf to the East Coast per month–the highest three-month average since the same time period in 2015, forcing some refiners to turn to the sea for crude oil shipments. Monroe Energy and Phillips 66 have both used U.S. tankers to bring Gulf Coast crude to the East Coast.

It is estimated that the pipeline capacity out of the Permian basin could be short by about 750,000 barrels a day by September 2019, when Permian production is estimated to hit 4.25 million barrels per day. However, several pipeline projects are being developed, with at least 1.5 million barrels per day of new capacity expected by late 2019. For instance, Plains All American Pipeline is building the Cactus II pipeline system with an initial capacity of 585,000 barrels per day to carry crude from the Permian Basin to Corpus Christi, Texas for $1.1 billion, which is expected to open around the third quarter of 2019. The Gray Oak Pipeline, being built by Phillips 66 and Enbridge, is expected to move 700,000 to 1 million barrels per day from West Texas to the Corpus and Houston region during the second half of 2019.

There are currently 15 rail loading terminals in the Permian region with the ability to load 500,000 to 600,000 barrels per day. A ramp-up in rail shipments would require additional infrastructure, including cleaning rail cars, which rail companies may not want to invest in due to the uncertainty of how long the price differential and shipping bottleneck may last. In the last seven years, only 46,000 barrels of crude have been shipped by rail to the East Coast from the Gulf region–all in June 2017. Crude deliveries by rail may not be able to increase quickly enough to meet the short term demand.

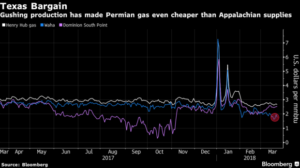

Not only is the Permian Basin constrained by oil pipeline capacity, but natural gas pipeline capacity is also having an impact on the region. About a third of the output from the Permian Basin is natural gas. Natural gas pipeline capacity has not kept up with the increases in natural gas production there. The pipeline shortage resulted in Permian natural gas prices recently being at the lowest price of any major U.S. hub—over 30 percent lower than Henry Hub. Permian gas could average $1.85 per million British thermal units this year. (See chart below.)

If natural gas production has no outlet due to pipeline constraints in the Permian Basin, drillers may be forced to curtail oil production. State regulations limit the amount of gas that can be burned off (flared). Further affecting natural gas production is spring weather, which lowers the demand for natural gas as a heating fuel, and wind generation, which picks up in the spring, displacing gas-fired power plants.

Mexican demand has helped a bit, but even that outlet is limited by pipeline capacity, mostly in Mexico. Natural gas exports to Mexico could stagnate at approximately 4.3 billion cubic feet per day as a result of bottlenecks and delays in several key pipeline construction projects, two of which traverse the U.S.-Mexico border while eight are within Mexico. These pipeline projects are facing delays due mainly to right-of-way disputes or social/indigenous protests.

Canada—Oil Sands

Alberta’s oil sands production needs more pipelines to get its oil to export markets. Despite being in the national interest, Prime Minister Trudeau is having problems getting the Trans Mountain pipeline built to the west coast because British Columbia does not want it running through its province. The C$7.4 billion ($5.9 billion) expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline would link Alberta’s oil sands to the Pacific Coast. Kinder Morgan halted work on Trans Mountain pipeline in April and set a May 31 deadline for a resolution. That led to an announcement May 29 that the Canadian Government would purchase Trans Mountain for C$4.5 billion ($3.5 billion), in order to ensure its construction. Opposition and uncertainty led to this development. Expanding Trans Mountain — in operation since 1953 — would transport an additional 590,000 barrels a day from Alberta’s oil sands to a terminal near Vancouver.

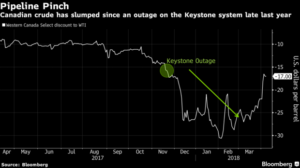

According to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Canada’s oil production growth could surpass pipeline capacity by the mid-2020s. An outage on TransCanada’s Keystone system last year caused Western Canada Select crude’s discount to West Texas Intermediate to its widest point in four years. At current levels, discounts to Canadian crude primarily due to pipeline bottlenecks could cost producers roughly C$15.6 billion ($12.4 billion) a year. Opponents of more oil and gas exploration know these costs steer investment away from the areas with transportation bottlenecks, and therefore see opposition to pipelines as a way to stop more oil and gas exploration and development.

Conclusion

Both oil and natural gas pipeline capacity is being limited, resulting in bottlenecks that either raise prices when demand is high such as in the Northeast during cold winters or cause supply prices to be discounted, which is occurring to producers in the Permian Basin in Texas and the Alberta province in Canada. Pipeline capacity is being constrained due to environmental protests to limit oil and natural gas production or due to right-of-way issues. Without sufficient pipeline capacity, consumers could face energy shortages and skyrocketing prices.