Oren Cass of the Manhattan Institute has published a fascinating critique of some recent studies that vastly overstate the danger of climate change. In this post I’ll walk through one of his strongest points, where he demonstrates that the climate change studies under review ignore the obvious ability of humans to adapt to a warming climate. Specifically, these studies assume that northern cities in the U.S. won’t be able to deal with “hot days” by the year 2100, as well as southern cities can deal with them right now.

Cass Explains the Technique

Here’s how Cass explains the procedure by which some recent estimates generated enormous human costs due to climate change by the end of the century:

The EPA estimate of costs due to additional heat deaths in 2100 relies on [the study] Mills. Mills studied the effect on mortality rates from days of “extreme” heat (or cold) in 33 cities…

Using climate models, the researchers then estimated for the years 2000 and 2100 a distribution of daily temperatures for each city. In 2000, the climate model’s simulation of Pittsburgh had fewer than five extremely hot days; for 2100, it had approximately 70, each of which Mills assumed would have the elevated mortality level associated with extremely hot days in the past.

Overall, Mills estimated that extreme-heat deaths in the 33 cities studied would rise from fewer than 600 in 2000 to more than 7,500 in 2100, even if their populations remained constant.

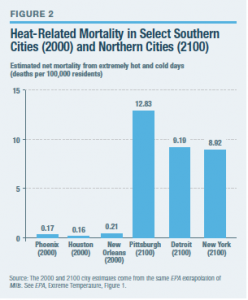

EPA employed the Mills methodology but used a different climate model…and accounted for population growth over the century. In the EPA model, Pittsburgh’s annual death rate from extreme temperatures increases 30-fold, from 0.4 per 100,000 people in 2000 to 12.8 in 2100. Across all cities, excess fatalities by 2100 would exceed 12,000. [Cass p. 7, endnotes removed.]

To paraphrase, the EPA’s estimate of (some of) the costs of climate change first calculated how many people died in cities like Pittsburgh on extremely hot days, which occurred only a handful of times in the year 2000. Then, using computer simulations of climate change, the number of extremely hot days in the year 2100 was expected to rise to around 70. It was assumed that the impact of such days on fatalities would be the same in 2100 as it was in 2000, but since there would be so many more such days, the mortality rate exploded.

The Flaw

The tremendous flaw with this method, of course, is that it assumes humans will not adapt to the warmer climate, even though they have eight decades to do so (and will be far richer in 2100 than we are now). But it is well known that if, say, someone moves from the north down south, that his or her body eventually adjusts. Beyond this physiological adaptation, there are obvious changes in building design and work routines that could reduce mortality rates from extreme heat.

This isn’t speculation. Oren Cass provides the following, absolutely devastating argument against the absurdly high predictions coming from these particular studies:

To repeat, the alarmist estimates of “damages from climate change” are driven by predictions that northern cities will suffer huge increases in heat mortality by the year 2100. Yet as Cass’ Figure 2 shows, these warnings assume that northern cities in the year 2100 will have mortality rates from “extremely hot days” that are forty to seventy-five times as high as what southern cities experienced in the year 2000.

A Snow Analogy

It might be difficult for the reader to understand just how silly this is, so let’s use an analogy. (Cass himself used the same one.) People from up north are used to driving in the snow: They know how to handle their vehicles better, and the authorities have more plows, salting trucks, etc. to deal with a major storm. Consequently, if a snowstorm of a given magnitude hits a city like Boston, it doesn’t cause nearly as many fatalities as if the same storm were to hit Atlanta.

But suppose that over the course of decades, people living in Atlanta got hit with as much snow during a typical year as Boston experiences right now. In that case, the people of Atlanta would begin to exhibit Bostonians’ resilience in the face of Mother Nature. They too would learn how to drive better in the snow, and the local governments would buy the appropriate equipment to keep the roads operable. It would be foolish to look at the spike in traffic fatalities in Atlanta during the worst snowstorm it got in the year 2000, and assume the experience would stay the same even if Atlanta got hit with 70 such storms during the year.

Conclusion

Oren Cass’ new paper shows how several recent studies have grossly exaggerated the potential harms from climate change. In this blog post, I outlined one of the most obvious problems in the techniques used. Specifically, these studies looked at extreme weather events in the past, and assumed that even if such events became commonplace by the year 2100, that humans would be unable to adapt and reduce their vulnerability during the 80 years in between.

Cass’ paper has many other excellent points. I encourage those interested in the climate change policy debate to read it in its entirety.