As debate intensifies around the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed carbon dioxide rule, EPA’s supporters are pushing back against claims that the economic costs of the rule outweigh the climate benefits. For instance, in a recent opinion piece for the Arizona Republic, University of Arizona law professor Kris Mayes claims that a widely cited study by NERA Economic Consulting fails to account for “energy efficiency investments that save money for consumers.”

This criticism of NERA is unfounded. In fact, as NERA and others explain, it is EPA who has failed to accurately calculate energy efficiency and other impacts, resulting in dramatically underestimated costs. Even the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office (GAO) has criticized EPA for using data that is more than two decades old, resulting in cost-benefit analyses that are “limited in their usefulness.” Furthermore, EPA’s analysis of energy efficiency is flawed because the agency assumes that even though energy efficiency measures help people, the only way people will implement these measures is if EPA mandates them through regulation.

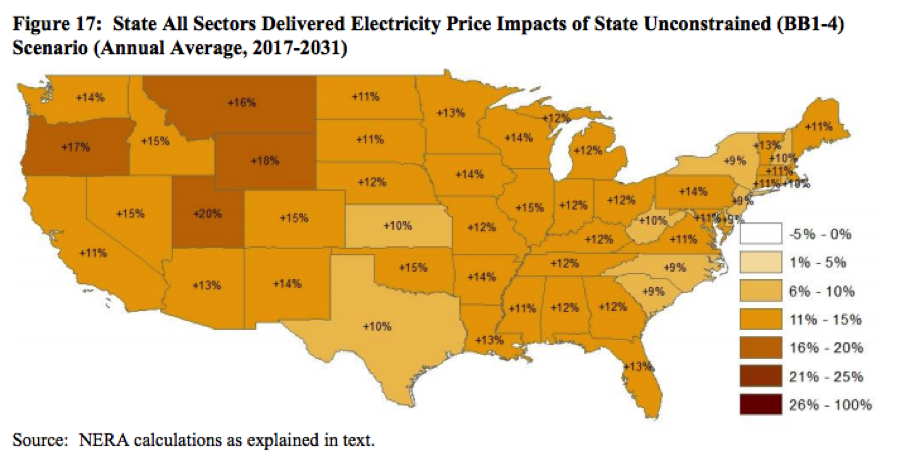

Below we review two major studies highlighting the economic costs of EPA’s proposed rule. First, a study by NERA finds that residents in 43 states would see double-digit electricity rate hikes under EPA’s plan. NERA also criticizes EPA’s flawed methodology on energy efficiency, which means “the potential impact to the economy is likely understated.” Second, a study by Energy Ventures Analysis (EVA) shows that EPA’s Clean Power Plan, along with other agency rules, would increase electric and natural gas bills by 35 percent. EVA also discusses EPA’s flawed assumption about electricity demand, which puts EPA at odds with the Energy Information Administration (EIA), resulting in “less severe” cost impacts “than they would be under a more realistic” methodology.

NERA Economic Consulting

In October 2014, NERA Economic Consulting released a report analyzing the economic impacts of EPA’s carbon dioxide rule for existing power plants. The report found that the rule would cost least $366 billion by 2031 and that residents in 43 states would see double-digit percentage increases in their electricity bills. Meanwhile, the benefits of compliance are miniscule: the rule limits global warming by just 0.02 degrees and lowers sea level rise by just 0.01 inch, according to EPA’s models. The following chart shows percent rate hikes by state:

Some claim NERA underestimates the value of energy efficiency, which results in an overestimation of costs. For example, EPA claims its rule will result in only modest, short-term electricity rate hikes and actually save consumers money long-term due to energy efficiency measures.

There are reasons to doubt EPA’s cost-benefit analysis. Last year, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office (GAO) criticized the methods EPA uses to conduct regulatory impact analyses. In one instance, EPA measured employment impacts for a particular rule using economic data that was more than 20 years old and may not have even applied to the industries being regulated. According to GAO, “Without improvements in its estimates, EPA’s RIAs may be limited in their usefulness for helping decision makers and the public understand these important effects.”

In Appendix C of its report, NERA explains why its energy efficiency calculations differ from EPA’s, resulting in dramatically different cost-benefit estimates. Essentially, EPA assumes that energy efficiency measures would be adopted in full under its proposed rule but not at all in the absence of the rule. This is illogical, as EPA also claims that these energy efficiency measures are beneficial to consumers without the rule. Thus, if energy efficiency is beneficial regardless of EPA’s regulation, then “rational consumers would adopt the changes without the need for a government program,” according to NERA. That means energy efficiency should be included in the baseline analysis—which NERA does but EPA does not—and not as a benefit of the rule. By counting energy efficiency as a benefit of the rule, “the potential impact to the economy is likely understated.”

Energy Ventures Analysis

In November 2014, Energy Ventures Analysis released a report assessing the cost impacts of selected EPA regulations. EVA examined the regulation of carbon dioxide emissions from existing power plants, the Mercury Air Toxics Rule, Regional Haze, and various market factors. Key findings include:

- Residential electric bills increase $341 in 2020 compared to 2012, a 27 percent rise. Mississippi families pay $854 more, most in the country. Nationally, residents in 47 states see double-digit percent increases in overall electric bills.

- Residential natural gas bills increase $339 in 2020, a 50 percent increase compared to 2012. Families in Northeast and Upper Midwest states are most severely impacted, shouldering increased bills of over $1,000 in 2020.

- In 2020, combined residential electric and natural gas bills increase by 35 percent, or $680 per household. States with the largest household increases are Maine (100 percent), Mississippi (63 percent), Connecticut (63 percent), Illinois (61 percent), and Texas (54 percent).

Similar to NERA, EVA also questions EPA’s cost-benefit analysis. EPA predicts negative growth in overall electricity demand between 2020 and 2030. This is unlikely. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates annual growth in electricity demand of 0.7 percent from 2012 to 2020 and 0.8 percent from 2020 to 2030. By contrast, EVA’s model is more closely aligned to EIA’s than EPA’s. As EVA explains, electricity demand is a key assumption that can have a dramatic impact on the cost-benefit analysis:

Additionally, this assumption affects several key results in the regulatory analysis. For instance, negative electricity demand growth reduces the amount of power generation and fuel needed to meet electricity demand and limits the need for new generating capacity to meet electricity reserve margin targets. Therefore the cost impacts of the EPA’s CPP will be less severe than they would be under a more realistic electricity demand assumption. [Emphasis added]

Conclusion

Cost-benefit analysis is a challenging but essential element of rulemaking. It requires agencies to use complex economic models to predict potential impacts for years into the future. Unfortunately, EPA is likely underestimating the economic costs of its proposed carbon dioxide regulation by using flawed assumptions about energy efficiency and electricity demand. Even the nonpartisan GAO questions the reliability of EPA’s cost estimates. The bottom line: the public shouldn’t look to EPA for a realistic assessment of economic impacts.