One of the recurring themes of my IER posts has been to warn Americans that the promises of a “win-win” from a carbon tax swap deal are very dubious. In the present post, I will draw on a 2013 Resources for the Future (RFF) study recently touted by the Niskanen Center—which is for a carbon tax swap deal—to show that even they aren’t expecting it to actually help the economy.

Carbon Tax Swap Deal: The Background

Advocates have claimed that so long as the revenues of a new carbon tax are used not to fund new government spending, but instead to reduce other taxes, then we can reduce climate change and stimulate the economy. I have shown over and over that the peer-reviewed literature considers this result is very unlikely even in theory. It will certainly not happen in practice once we factor in the realities of the political process.

As if to confirm my warnings, the Niskanen Center’s recent post explaining the policy options available for a carbon tax swap deal underscores that the economy will be hurt even with a revenue-neutral carbon tax. The only question is which groups will bear the brunt of the economic loss, in exchange for the modeled avoidance of future damages from climate change.

The Niskanen Center Framing of the Carbon Tax Swap

Here is how the Niskanen Center author, Shi-Ling Hsu, motivates the 2013 RFF study:

[T]here is little dispute among economists that a carbon tax is, at the household level, regressive. The increased energy costs take up a larger fraction of a poor household’s budget than a rich one’s. But the sophisticated discussion about a carbon tax has always been about what do to with the carbon tax revenues, because that makes all the difference. Some options laid out in a 2013 Resources for the Future paper by Carbone et al, include: (A) reduction of capital taxes… (B) reduction of personal income taxes, including payroll taxes; (C) reduction of sales taxes… (D) rebate of the carbon tax proceeds as a lump-sum distribution to every household in the U.S.; and (E) deficit reduction. These are the serious options, and form the basis for further discussions about carbon taxes.

Actually I would challenge Hsu’s claim that these exhaust the “serious options,” if that means the ones that prominent economists and political officials are discussing. Any “serious” proposal that has a chance of becoming law at the federal level will almost certainly earmark some carbon tax revenues to “green” investments and/or new spending that specifically targets low-income groups who are particularly hard hit by higher energy prices. In terms of promoting general economic efficiency, both of these options are worse than the ones Hsu lists.

For some real-world examples of my claim: Governor Jerry Brown eyed California’s cap-and-trade revenue for high-speed rail. The website for the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)—which is the cap-and-trade program for power plants in participating Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states—openly brags about how its revenues have been spent on renewables, energy efficiency projects, and other “green” investments. For a final example, Washington State Governor Jay Inslee wants to install a new state-level cap-and-trade levy on carbon emissions to fund his $12.2 billion transportation plan.

But let’s put all of these real-world examples aside, and take Hsu’s framing, based on the 2013 RFF paper, at face value. In other words, we will bend over backwards to help the case for a new carbon tax, by assuming that 100% of its new revenues are given back to citizens either through other tax reductions or through lump-sum rebates. Even so, we will see that the RFF paper itself shows that there is net harm to the economy from every single option discussed.

The RFF Model of a Carbon Tax Swap

The 2013 RFF paper “looks at both the efficiency and distributional implications of introducing carbon dioxide…taxes, either as part of revenue-neutral tax reform or as one of a series of measures to address the long-term budget deficit.” It is superior to previous models in this genre because it employs a more realistic “overlapping generations” approach with disaggregated sectoral impacts. As always with such models, one must make many heroic assumptions to get anywhere with the analysis, but this particular model is fine as far as it goes. As we will see, even with very generous assumptions on the trustworthiness of government officials to be careful with the new carbon tax receipts, the RFF model shows that it will hurt the economy overall.

RFF: Even a Perfect Carbon Tax Swap Hurts the Economy

First let’s quote from the RFF study’s own executive summary:

When the…tax proceeds are used to support revenue-neutral reductions in capital taxes…we find that the net social costs, even without considering the environmental benefits, are close to zero: gross domestic product rises slightly, though a more comprehensive measure of economic effects shows a small net cost. Recycling the revenues via reductions in payroll taxes or personal income taxes is slightly less economically efficient than via capital tax cuts. Recycling via lump-sum rebates is worse than the other options in terms of economic efficiency.

Don’t let the spin fool you: The RFF study’s authors are telling us that even if 100% of the revenues from a carbon tax are devoted exclusively to reducing taxes on capital gains, profits, interest, and dividends, that it will still hurt the economy.[1] Once we move away from that benchmark, things just get worse, even if we are still restricting ourselves to the hypothetical world in which Congress dutifully returns every penny of the new trillions in carbon tax revenues to the citizens through other tax cuts or flat rebates.

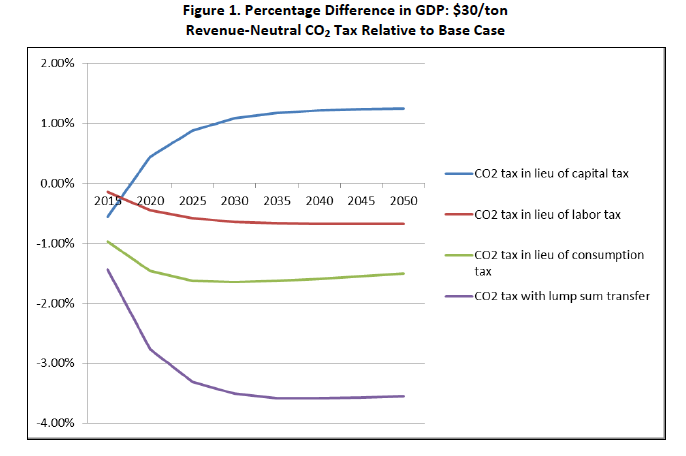

And here is a chart from the RFF study to illustrate its results:

SOURCE: Resources for the Future, page 8.

SOURCE: Resources for the Future, page 8.

The chart above shows the results from a hypothetical $30/ton carbon tax, which the study estimates will bring in $226 billion annually in new revenues. The chart above shows what happens to GDP when 100% of the new revenues are used in one of four ways: (1) Reduce tax rates on capital (i.e. corporate profits, capital gains, interest, and dividend income). (2) Reduce tax rates on labor (i.e. wage/salary income or payroll taxes). (3) Reduce sales taxes. (4) Give lump-sum checks to every citizen, estimated in this scenario to be $876 per person annually.

To be clear, these modeling assumptions totally stack the deck in favor of the carbon tax deal. Not a single penny of the new revenue is devoted to new spending. And yet, in the early years every single technique reduces total GDP relative to the baseline (with no carbon tax). Further out, the only technique that ends up raising GDP is the one in which all of the new revenue is exclusively devoted to providing tax cuts for corporations and capitalists. (How politically likely is that outcome?)

Notice in particular the red line, which shows the results when 100% of the $226 billion in annual new revenues from the carbon tax are used to reduce tax rates on personal income and the payroll tax. This is the scenario that is typically touted by the few supply-side economists who want to strike a carbon tax swap deal with the environmental Left. Conservative audiences have been assured that if the Left would abide by such a deal, we would get a “win-win.” And yet, as the chart above indicates, the red line is in the negative region. In other words, GDP will be permanently lower even with a revenue-neutral carbon / payroll tax swap deal. Thus we see that those treating the “win-win” as a no-brainer are misinformed.

Conclusion

The idea that Congress could be trusted to “recycle” hundreds of billions annually in new revenue back to citizens—either through other tax cuts or direct rebates—is laughable. Yet even a sympathetic RFF study, touted recently by the Niskanen Center, a group that is favorable to the proposal, shows that even on paper such a deal will make the economy worse. If things are this bad in theory, think of how much a new carbon tax would hurt the economy in practice.

[1] To be clear, the RFF authors could still support such a carbon tax, because they think there will be benefits to the environment that outweigh the harms to the economy. But the important point—which contradicts the assurances of many people claiming a “win-win” outcome—is that even under the most idealistic of modeling scenarios, the sympathetic RFF authors found that their carbon tax would hurt the economy.