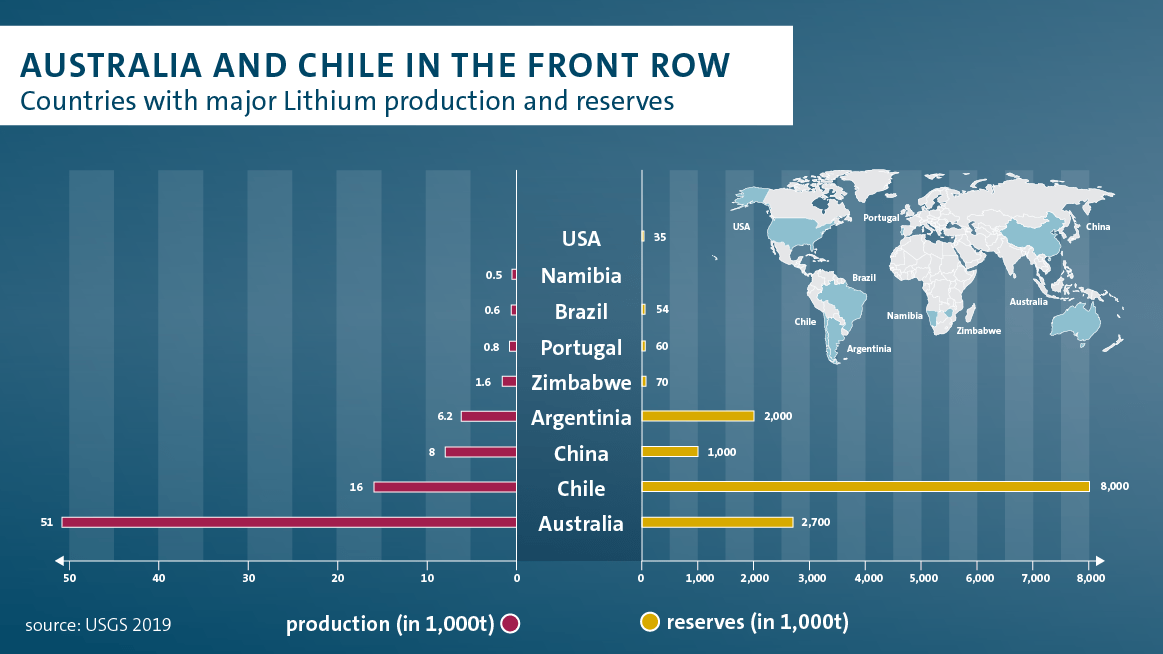

Chile, hailed as the Saudi Arabia of lithium, accounts for 55.5 percent of the world’s known deposits of the metal—a key component in electric-vehicle batteries. But, on September 4, the citizens of Chile will vote on a proposed constitution that could destroy Chile’s economy, democracy and integrity as a nation and that will radically impact its mining industry. If approved, the country will depart from the pro-mining orthodoxy that has defined it since the late 20th century, which will have a significant impact on the expansion of mines required for the world to meet electric vehicle sales goals. Chile has the world’s largest reserves of both lithium and copper, both critical to electrification and the energy transition bandwagon.

The new constitution would get rid of existing regulations on eminent domain, allowing the Chilean government to confiscate any type of private property by simple legislative decree without having to compensate the owners at market prices. Intellectual-property rights such as patents would have no protection, and water rights, protected under the existing constitution, would be scrapped so that economic activities requiring water—such as mining and agriculture—would be vulnerable to arbitrary administrative decisions. Property rights over mining concessions would also cease to exist. In Chile, where lithium is already tightly controlled, Chile’s new Left-wing President Gabriel Boric’s government plans to create a state lithium company, despite having criticized past privatizations of raw commodities as a mistake.

Earlier this year, the Chinese electric vehicle company, BYD, won a government contract to mine lithium. But indigenous residents protested, demanding the tender be canceled over concerns about the impact on local water supplies. In June, the Chilean Supreme Court threw out the award, saying the government failed to consult with indigenous people first. The new constitution, if approved in September, would strengthen environmental rules and indigenous rights over mining.

Lithium production has fallen as leftist governments want greater control over the mineral and a bigger share of profits and as local communities to bring up environmental concerns. Setbacks are occurring around the so-called Lithium Triangle, which overlaps parts of Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. The Bolivian government nationalized its lithium industry years ago and has not yet produced meaningful amounts of the metal. Mexico also recently nationalized lithium. In Argentina, production is just starting to grow.

Lithium prices increased 750 percent since the start of 2021 due to skyrocketing demand created by government mandates for electric vehicles. The automotive industry is worried that South America could become a major bottleneck for meeting electric vehicle targets. Chile is the world’s top producer of copper and the second largest producer of lithium. Because Chile has 8 million metric tons of lithium–55.5 percent of the global total, it is instrumental to the global transition to renewable technologies and electric vehicles. The world’s ability to build new electric vehicles, utility-scale energy storage for renewables, and high voltage cabling required for upgrades to the electricity grid, requires consistent production from current and new mines in Chile. If passed, the constitution would result in a future where electric vehicles remain out of reach due to copper and lithium supply constraints pushing up input costs for automobile manufacturers. For California to meet its new targets to phase out the sale of fossil fuel vehicles by specified future dates, Chilean production of lithium is required. Batteries currently constitute around 40 percent of the cost of manufacturing an electric vehicle.

Tesla Production Goals

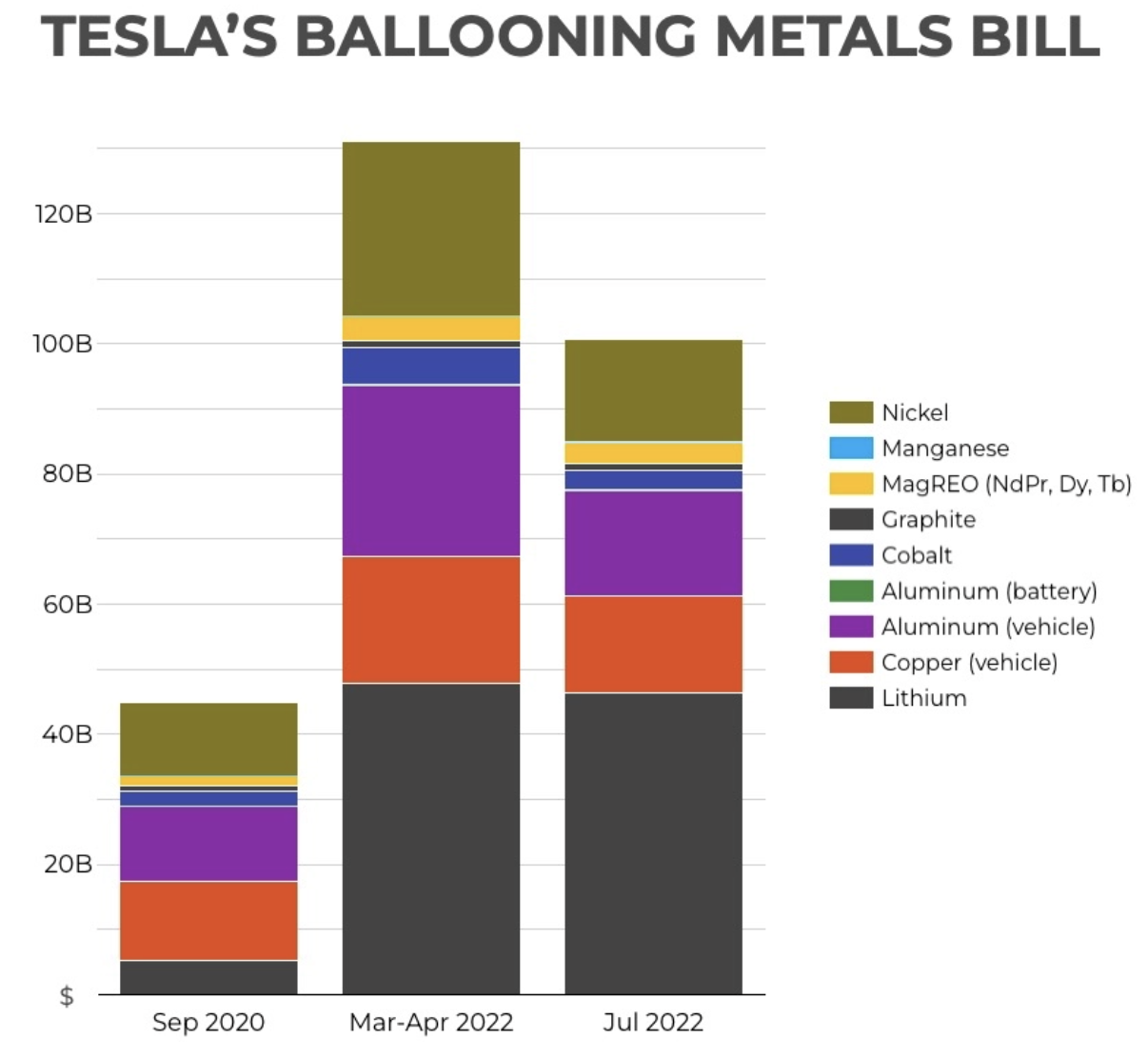

Tesla’s produced 3 million electric vehicles since its first production in 2008 and aspires to manufacture 20 million cars per year by 2030. The company is expected to deliver 1.4 to 1.5 million vehicles in 2022. At today’s mineral prices, to build 20 million cars, it would cost over $100 billion for the 11.1 million metric tons of raw materials it would need—more than double the $44.8 billion those metals cost at the time that Elon Musk announced the production goal in 2020. The increased cost is mostly due to the 8-fold increase in the price of lithium over the period, which in July averaged more than $60,000 per metric ton.

In July, lithium made up 46 percent of the total mineral cost, while in September 2020 it was only 11.6 percent. Nickel made up 25 percent of the overall cost of materials two years ago and now it represents 15.7 percent despite its price increasing 40 percent since then. In March-April when battery metals were hitting multi-year and all-time highs, the total mineral cost was $131 billion. While some of the mineral prices have recently declined, by the end of the decade, these commodities will likely become more expensive as demand outpaces supply, especially with government policies mandating electric vehicles. Government policies are literally pushing the world into a minerals crisis, and with it, geopolitical challenges around the world.

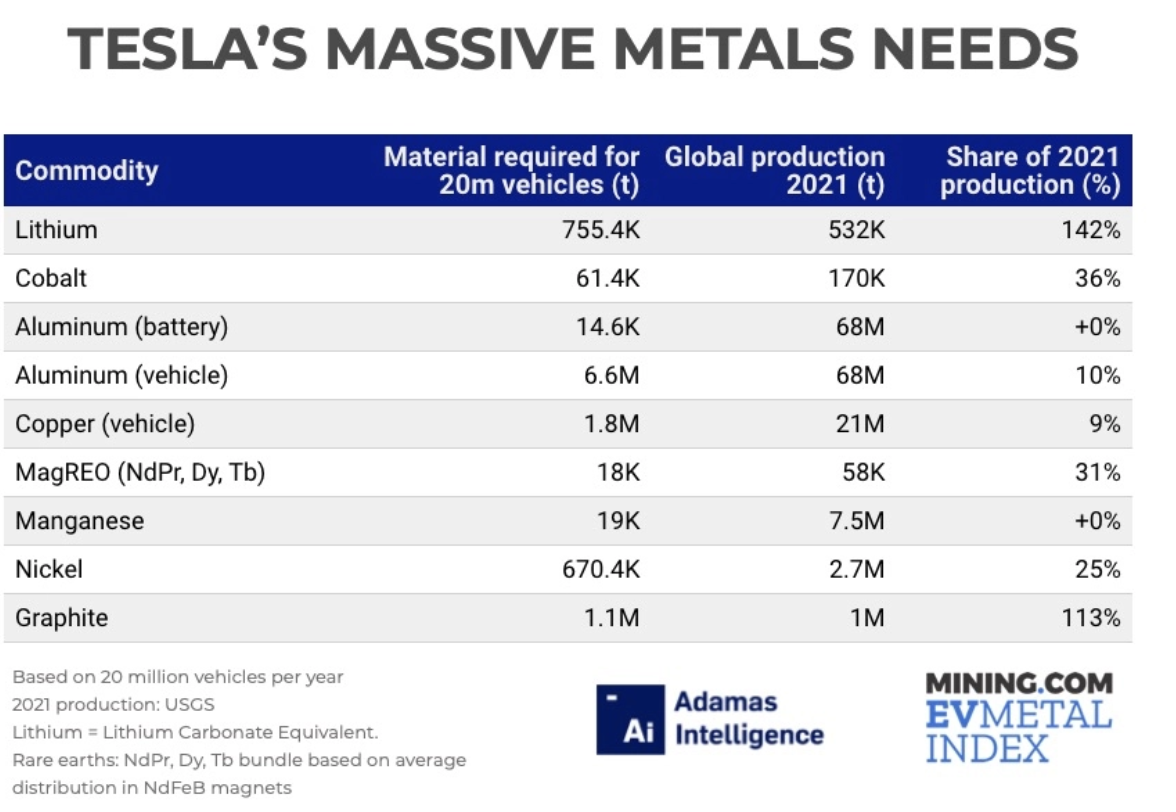

To produce 20 million vehicles, Tesla needs more than the total volume of lithium and natural graphite produced last year, almost a third of the rare earth minerals, and 36 percent of the cobalt. No single company consumed 1.8 million metric tons of copper per year and obtaining a quarter of the world’s nickel may not even be possible. (See table below.) As automakers and the renewable energy sector search for lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, rare earth minerals, aluminum, manganese and copper, obtaining supply may ultimately be a bigger issue than their costs. And costs have been exploding. Aluminum plants in Europe have stopped producing because of very high energy costs.

Lithium Mines Have Problems Globally

It is just not in Chile and South America that lithium mining is having trouble. In Serbia, Rio Tinto’s proposed $2.4 billion Jadar lithium mine, which would have become the largest lithium mine in Europe, was canceled by the Serbian government after protests against it. In the United States, the Thacker Pass lithium mine being developed by Lithium Americas Corp in Nevada is currently in a legal battle after multiple lawsuits by environmental and indigenous groups. That region in Nevada forms one of the largest lithium deposits in the United States. In Portugal, the proposed Barroso lithium mine which was meant to begin production in 2020 has a new date set in 2026 due to protests and the inclusion of an additional phase by Portugal’s regulator in the environmental approvals process.

Conclusion

The world needs Chile’s lithium and copper resources for its transition to renewable energy and electric vehicles, otherwise, there will be a limited supply pipeline which will drive up the mineral costs, making renewable technologies too costly even with sizeable incentives and subsidies. The vote on Chile’s proposed new constitution will be a defining factor in the country’s mining future and the world’s availability of lithium. According to the Chilean government, the new constitution is an attempt to correct environmental issues associated with mining. But if passed, it would likely setback the global race towards reaching net zero carbon emissions.

Environmental issues associated with the mines required to produce the critical metals that electric vehicles and renewable technologies require are causing long delays in mine approvals due to numerous lawsuits. In the United States, environmentalists and the Biden Administration are against opening new critical mineral mines even though the United States has the strictest global regulatory standards and would be the most environmentally benign to their production. It is easy to see that without significant changes, Americans are going to soon see what French President Emmanuel Macron warned his people about: “the end of abundance.” If Americans suffer, they should know that it is politics, not geology, which made their lives worse.