COP26, or Conference of the Parties, was the 2021 gathering of a group of nations that agreed to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. This year the summit was held in Glasgow, Scotland. What was revealing in this year’s confab was that both developed and developing countries are recognizing that a net-zero carbon pledge will be disastrous for their countries. India’s Prime Minister Modi took a swipe at developed nations that are trying to persuade India to cut down its carbon dioxide emissions because these developed nations have been the biggest emitters of carbon dioxide and have benefitted from fossil fuel-powered industrial and economic growth. In Japan, government officials are quietly urging trading houses, refiners and utilities to slow down their move away from fossil fuels and encouraging new investments in oil-and-gas projects. China, the world’s largest consumer of coal and largest emitter of carbon dioxide, ramped up its coal production recently to deal with its power crunch that caused the government to curtail power production and reduce supplies to homes. Further, China’s greenhouse gas emissions now exceed the combined greenhouse gas emissions of all 41 developed countries.

India’s Pledge and Actions

At the COP26 Summit, Modi pledged to cut India’s emissions to net-zero by 2070. He also pledged to get 50 percent of India’s energy from renewable resources by 2030, reduce its total projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tons from 2021 till 2030, build 500 gigawatts of non-fossil electricity capacity by 2030, and reduce emissions intensity of GDP by 45 percent by 2030. But, by the end of COP26, India forced the summit communique to water down language on “phasing out” coal to just “phasing down.” It also demanded $1 trillion of public cash to be put up by the wealthy countries before the end of the decade for India to cut carbon dioxide emissions.

After two visits to India by John Kerry, Biden’s climate envoy, and a visit by COP26 president Alok Sharma, in late September, Modi visited Washington where the White House released a joint statement of the leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, discussing the aim of achieving global net-zero emissions by 2050. Yet, just before the start of COP26, India’s environment secretary R.P. Gupta rejected calls for his country to announce a net-zero carbon emissions target, stating, “It is how much carbon you are going to put in the atmosphere before reaching net-zero that is more important.” Earlier, at an April meeting organized by the International Energy Agency, India’s power minister Raj Kumar Singh called the “net zero by 2050” mantra pushed by the EU and the U.S. “pie in the sky . . . you have 800 million people who don’t have access to electricity. You can’t say that they have to go to net zero, they have the right to develop, they want to build skyscrapers and have a higher standard of living, you can’t stop it.”

India has 10 percent of the world’s coal reserves and generates over 70 percent of its electricity from coal. Its non-fossil-fuel-installed power-generating capacity (excluding nuclear energy) currently stands at 38.3 percent, consisting of 149.56 gigawatts of hydro, wind, solar, and other renewable resources, with a renewable energy target of 450 gigawatts by 2030. India’s fossil fuel capacity is over 50 percent higher—234 gigawatts. But, as renewable energy is scaled up, India has found itself increasingly in supply curtailment to ensure grid stability. A study conducted by Solar Energy Corporation of India projected that, at 450 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2030, the grid would have to curtail up to 50 percent of the solar power to keep the grid stable.

Japan

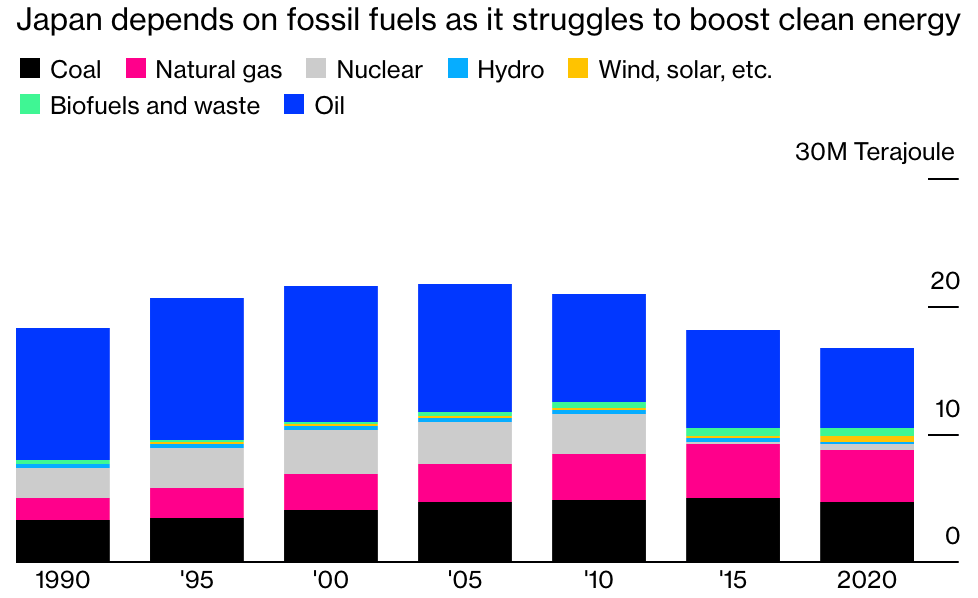

At COP26, Japan agreed with its pledge to phase down coal and to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. But, because Japan relies on imports for almost 90 percent of its energy, it is already changing its tune. The nation faced energy deficits last year, sparking fears of blackouts, which it wants to avoid this winter and in the future, particularly when prices are spiking in part due to the world’s shift away from fossil fuel investments. Japan has been slow to make any concrete commitments to phase out coal in the near term, and has funded coal plants overseas. Japan currently gets 30 percent of its electricity from coal. The government has also avoided joining efforts by developed nations to reduce consumption of natural gas.

In October, oil prices surged to the highest level since 2014, which many in Japan believe was exacerbated by a lack of investment in new supply. Further, liquefied natural gas prices jumped to a record due to a global shortage, pushing Japan’s wholesale power rate to the highest level for this time of year. The belief is that Europe’s natural gas supply shortages are proof that nations need to continue to add more production. Japan’s strategic energy plan states “no compromise is acceptable to ensure energy security, and it is the obligation of a nation to continue securing necessary resources.” The latest strategy calls for the share of oil and natural gas produced either domestically or under the control of Japanese enterprises overseas to increase from 34.7 percent in fiscal year 2019 to more than 60 percent in 2040. The Japanese are serious about energy security.

China

Despite China sticking to its climate pledge of net zero carbon by 2060 at COP26, it has relaxed efforts to curb carbon dioxide emissions and ordered coal mines to ramp up production to deal with a power crunch, as extreme weather, surging demand for energy and strict limits on coal usage delivered a blow to the nation’s electricity grid. In September, companies were told to limit their energy consumption in order to reduce demand for power and electricity was also cut to some homes. The energy crunch, along with surging raw material costs, resulted in a sharp drop in industrial output for September and October. China, which consumes over half the world’s coal supply and is the largest emitter of carbon dioxide, set a new daily record for coal production in mid-November. China has 13 percent of the world’s coal reserves and generates over 60 percent of its electricity from coal.

The crunch may not be over as the production of raw materials — which causes high levels of air pollution — may still be limited in northern China as the government tries to clean its skies for the Beijing Winter Olympics. Also of concern is the downturn in China’s property sector and the emergence of the Omicron COVID variant. The newest variant of the coronavirus has been labeled of “concern” by the World Health Organization because it seems to be fast spreading in South Africa and it has many mutations.

China’s coal fleet is already the largest on the planet and growing. In 2020, China’s coal fleet increased by a net 19 gigawatts (new plants minus retirements), bringing the size of China’s fleet to 1,080 gigawatts. China’s existing coal fleet represents slightly more than half the world’s coal-fired generating capacity (2,115 gigawatts) and is as large as the entire U.S. electricity supply (natural gas, coal, oil, nuclear, and renewables), which totals about 1,100 gigawatts. The U.S. coal fleet totals 217 gigawatts of electric generating capacity, making China’s coal fleet more than five times the size of the U.S. coal fleet. China also has 247 gigawatts of coal-fired generating capacity (478 generating units) under development (under construction, permitted, or announced).

For China to achieve its net-zero emissions target in 2060, investments of as much as $2 trillion a year will be required until 2060. That includes more than tripling its current pace of renewable-energy installations. According to China’s Premier Li Keqiang, China cannot easily pivot away from coal until it has enough other alternatives to ensure reliable power. He hinted that a pledge to cap the country’s carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 could be torn up.

South Africa

South Africa gets more than 80 percent of its electricity and nearly one-fifth of its liquid fuel from coal. It is one of the top-10 coal producers in the world and has spent the equivalent of 6 percent of its annual gross domestic product on two huge coal-fired power plants that will become fully operational in the coming years. It is the most coal-dependent country in the Group of 20 major economies.

South Africa is willing to help achieve the goals of COP26—provided that wealthy countries, along with international development banks, pay over 400 billion rand ($26.6 billion) to transform its power system. At COP26, the U.S., Germany, France, the U.K. and the EU said they would mobilize $8.5 billion over the next three to five years to help South Africa quit coal by replacing coal plants with renewable energy and finding new livelihoods for mining communities. But, that is not enough money to even transition one country — South Africa —out of coal and into renewable energy.

Conclusion

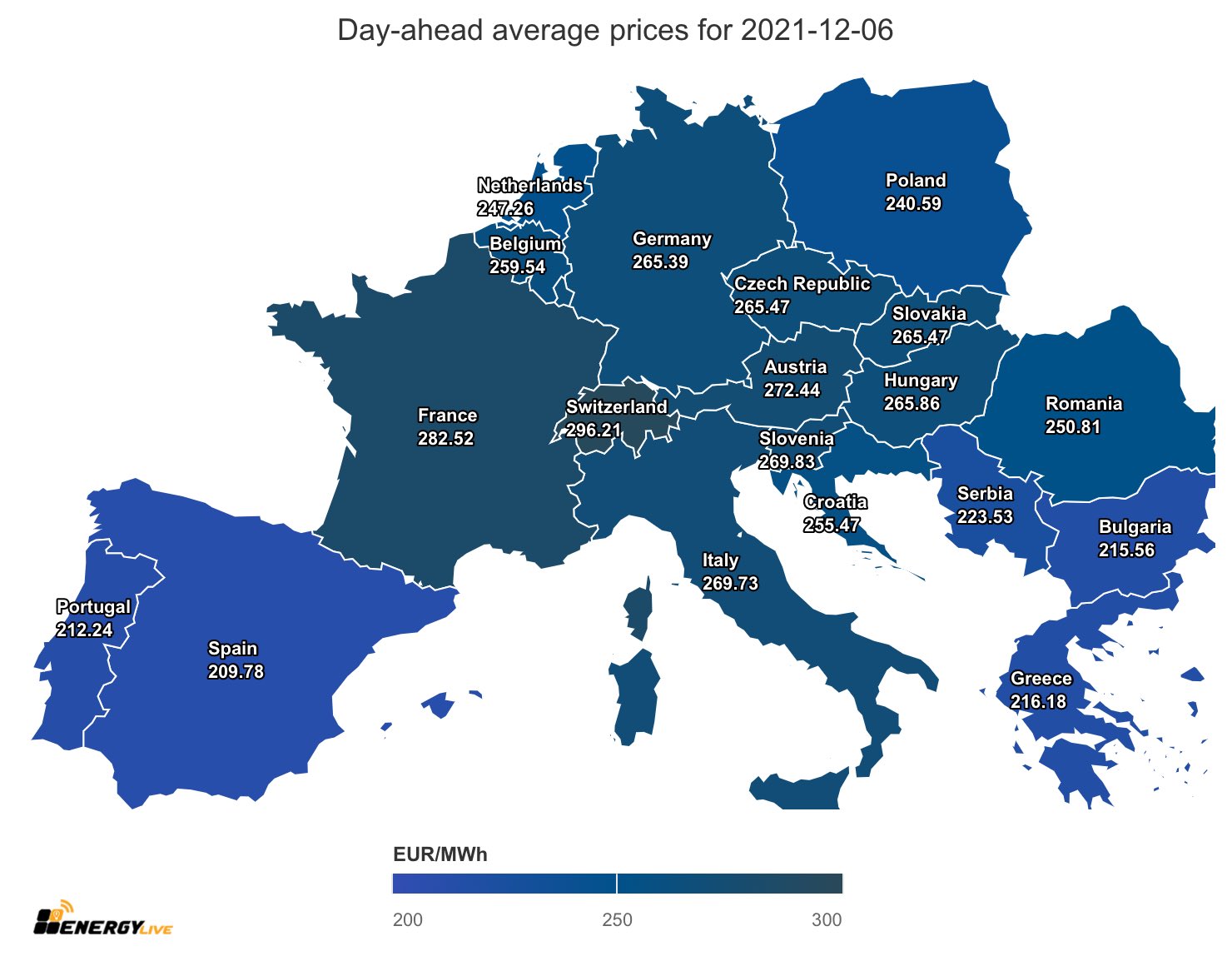

President Biden and his climate envoy, John Kerry, believe that they got a great environmental deal at COP26 and will improve upon it at the next summit. But, the above discussions concerning India, Japan, China and South Africa clearly show that the deal is essentially worthless. Nonetheless, these two people will continue to force net-zero carbon on the American public, increasing U.S. energy prices as has been seen over the past 10+ months.